9 Choice of Law and the Erie Doctrine 9 Choice of Law and the Erie Doctrine

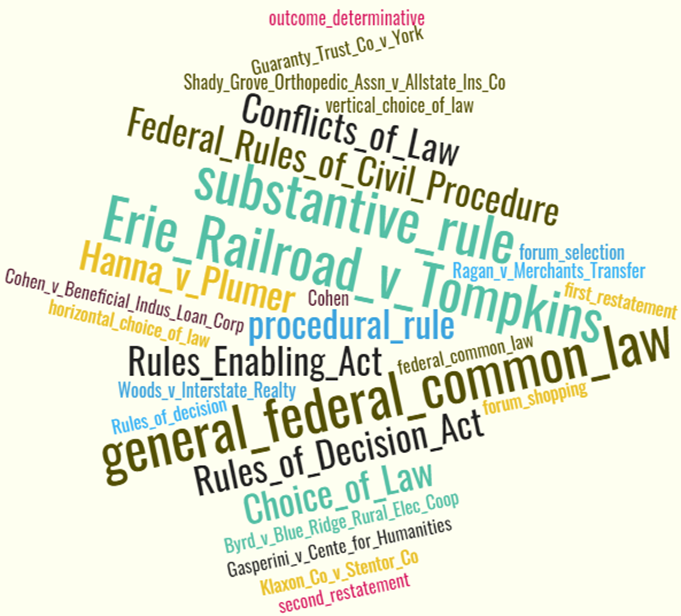

9.1 Choice of Law and Erie Wordcloud 9.1 Choice of Law and Erie Wordcloud

9.2 Choice of Law Generally - Horizontal Choice of Law 9.2 Choice of Law Generally - Horizontal Choice of Law

9.2.1 Horizontal Choice of Law Background 9.2.1 Horizontal Choice of Law Background

The coverage in this chapter will be somewhat summary. The goal is to give you awareness of these doctrines but to reserve the time required for a deep look for other topics that I consider more important for our purposes.

As you recall from our look at personal jurisdiction, the idea of territoriality is important to courts in the US. Courts, state and federal, sit in a given location, and the powers they can exercise are often determined by that location. In most cases, they will apply the law of the jurisdiction to cases before them.

But – not always. On occasion, courts will be asked to apply the law of a different jurisdiction. This can come about for many reasons. Not infrequently, parties to a contract will select the law that governs the contract. This can save much time and conflict if litigation arises later. For example, if parties from Shenzhen, China, and New York City in the United States meet at a trade show in Singapore to negotiate a purchase contract for widgets, which are to be shipped to Long Beach, California, with title passing to the purchaser when they are loaded on board a container ship in Hong Kong, there may be room for debate with regard to whose law applies to any dispute arising from the contract. A choice of law provision can avoid this debate if the governing law has a reasonable connection with the contract. Choice of law issues also arise when there is no pre-existing agreement but there is an issue as to which jurisdiction's law should apply. You may recall that just such an issue arose in the Chinese Drywall litigation with regard to imputing the behavior of subsidiary corporations to the parent corporation. The court avoided this issue by concluding, somewhat interestingly, that the applicable law in China and the US state was identical:

TG faults the district court for applying the forum state's law (Florida law) instead of Chinese law to the question of whether to impute TTP's Florida contacts to TG. TG concedes, however, that “Chinese law is not materially different on this issue from Florida law, and the outcome should be the same under either law.” Accordingly, we need not choose because “if the laws of both states relevant to the set of facts are the same, or would produce the same decision in the lawsuit, there is no real conflict between them.” Phillips Petroleum Co. v. Shutts, 472 U.S. 797, 839 n. 20, 105 S.Ct. 2965, 86 L.Ed.2d 628 (1985). Therefore, we apply Florida law.

In re: Chinese-Manufactured Drywall Products Liability Litigation, 753 F.3d 521, 529 (5th Cir. 2014)

This kind of choice of law rules often goes by the name of conflicts of law, and generally involves a ‘horizontal’ choice between two different jurisdictions with some connection to the dispute. An extensive body of law has grown up nationally and internationally.

In the United States alone, there have been radically different approaches to choice (or conflict) of laws, summarized in and to significant degree affected by in the American Law Institute’s Conflict of Law Restatements. To oversummarize, the First Restatement applied what in quarter one we referred to as rules – simple, clear, somewhat rigid statements, such as that the law that applied to a tort claim was the law of the place where the tort occurred. The Second Restatement shifted the approach significantly, moving to a more standard-based approached where the jurisdiction with the most legitimate interest in providing governing law was to be identified.

Other nations have their own approaches. For example, in China, Article 6 of the Law of the Application of Law for Foreign-related Civil Relations makes it clear that as for application of foreign laws on a foreign-related civil relation, if multiple laws are enforced in different regions within the foreign country, the laws of the region that has the closest relation with this foreign-related civil relation shall apply. In the European Union, the rule to apply to contract based claims will be controlled by a regulation commonly known as Rome I (Regulation (EC) No 593/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 on the law applicable to contractual obligations). ("Rome I Regulation"). For non-contractual claims, a different regulation, commonly called Rome II (Regulation (EC) No 864/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 July 2007 on the law applicable to non-contractual obligations), generally follows a place of the tort (lex loci delicti for you Latin readers) approach to choice of law.

Choice of law is an important tool of great lawyers. Rules vary by jurisdiction and getting the court to apply to preferred rule for your client can determine success or failure. This can be done by contract (remember the Burger King case in the personal jurisdiction section, where when forming the relationship the parties had elected to have Florida law apply to any disputes) or it can be a determination the court makes in the absence of any agreement by the parties.

While conflicts of law is a standalone course, the following case will give you a taste of how courts approach such issues.

9.2.2 Excerpts from Restatement (First) and (Second) of Conflict of Laws 9.2.2 Excerpts from Restatement (First) and (Second) of Conflict of Laws

Restatement (First) of Conflict of Laws -- § 379 Law Governing Liability-Creating Conduct

Except as stated in § 382 [ed. note - which governs duty to act or privilege], the law of the place of wrong determines

(a) whether a person is responsible for harm he has caused only if he intended it,

(b) whether a person is responsible for unintended harm he has caused only if he was negligent.

(c) whether a person is responsible for harm he has caused irrespective of his intention or the care which he has exercised.

Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws -- § 6 Choice-of-Law Principles

(1) A court, subject to constitutional restrictions, will follow a statutory directive of its own state on choice of law.

(2) When there is no such directive, the factors relevant to the choice of the applicable rule of law include

(a) the needs of the interstate and international systems,

(b) the relevant policies of the forum,

(c) the relevant policies of other interested states and the relative interests of those states in the determination of the particular issue,

(d) the protection of justified expectations,

(e) the basic policies underlying the particular field of law,

(f) certainty, predictability and uniformity of result, and

(g) ease in the determination and application of the law to be applied.

Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws -- § 145 The General Principle

(1) The rights and liabilities of the parties with respect to an issue in tort are determined by the local law of the state which, with respect to that issue, has the most significant relationship to the occurrence and the parties under the principles stated in § 6.

(2) Contacts to be taken into account in applying the principles of § 6 to determine the law applicable to an issue include:

(a) the place where the injury occurred,

(b) the place where the conduct causing the injury occurred,

(c) the domicil, residence, nationality, place of incorporation and place of business of the parties, and

(d) the place where the relationship, if any, between the parties is centered.

These contacts are to be evaluated according to their relative importance with respect to the particular issue.

Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws -- § 146 Personal Injuries

In an action for a personal injury, the local law of the state where the injury occurred determines the rights and liabilities of the parties, unless, with respect to the particular issue, some other state has a more significant relationship under the principles stated in § 6 to the occurrence and the parties, in which event the local law of the other state will be applied.

9.2.3 General Motors Corp. v. Eighth Judicial District Court of the State of Nevada ex rel. County of Clark 9.2.3 General Motors Corp. v. Eighth Judicial District Court of the State of Nevada ex rel. County of Clark

GENERAL MOTORS CORPORATION, and CHAPMAN MESA AUTO CENTER, Petitioners, v. THE EIGHTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT OF THE STATE OF NEVADA, in and for THE COUNTY OF CLARK, and THE HONORABLE MICHELLE LEAVITT, District Judge, Respondents, and HEATHER SIMMONS, Real Party in Interest.

No. 44506

May 11, 2006

134 P.3d 111

*467Law Offices of Greg W. Marsh, Chtd., and Greg W. Marsh, Las Vegas; Bowman and Brooke LLP and Curtis J. Busby, Phoenix, Arizona, for Petitioner General Motors Corporation.

Lincoln, Gustafson & Cercos and Thomas J. Lincoln and Loren S. Young, Las Vegas, for Petitioner Chapman Mesa Auto Center.

Mainor Eglet Cottle, LLP, and Robert W. Cottle and Jennifer V. Willis, Las Vegas, for Real Party in Interest.

*468OPINION

By the Court,

In this original writ petition, we clarify Nevada’s choice-of-law jurisprudence in tort actions. We conclude that the most significant relationship test, as provided in the Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws section 145, should govern the choice-of-law analysis in tort actions unless a more specific section of the Second Restatement applies to the particular tort claim. Consequently, we no longer adhere to the choice-of-law analysis previously set forth in Motenko v. MGM Dist., Inc.1

FACTS

In April 2002, real party in interest Heather Simmons was driving her 1996 Chevrolet Metro on Interstate 15 in southern Nevada. Jerry Freeland was driving his truck a short distance ahead of Simmons. Freeland’s truck struck an object on the road that punctured his fuel tank and caused the tank to spill diesel fuel. When Simmons’ vehicle came into contact with the diesel fuel, she lost control and her vehicle overturned. As a result of the accident, Simmons was rendered a quadriplegic.

Simmons is an Arizona resident. Except for the accident and spending several weeks in Nevada for medical treatment, Simmons has no contact with Nevada. After the accident, Simmons *469brought suit against several defendants, including petitioners General Motors Corporation (GM) and Chapman Mesa Auto Center (Chapman Auto). The complaint alleges that Simmons’ injuries were caused by, among other things, the failure of her vehicle’s roof assembly. Simmons asserts causes of action against GM and Chapman Auto for negligence, breach of implied warranty, strict liability, negligent failure to warn, and negligent infliction of emotional distress.

GM is a Delaware corporation with its principal office located in Michigan. GM manufactured the 1996 Chevrolet Metro that Simmons was driving when the accident occurred. Chapman Auto is the independent auto dealer located in Arizona that sold the Chevrolet Metro to Simmons. Chapman Auto is not a GM dealer, nor is it affiliated with GM in any way.

GM and Chapman Auto sought dismissal of the case for forum non conveniens or, in the alternative, to have the district court apply Arizona law. The district court denied the motion to dismiss and determined that Nevada law should apply. As a result, GM filed this petition for a writ of mandamus, challenging the district court’s order and seeking to compel the district court to dismiss the case for forum non conveniens or, in the alternative, to apply Arizona law. Chapman Auto joins in this petition.

DISCUSSION

The decision to entertain a petition for a writ of mandamus lies within this court’s discretion.2 “A writ of mandamus is available to compel the performance of an act that the law requires as a duty resulting from an office, trust or station, see NRS 34.160, or to control an arbitrary or capricious exercise of discretion.”3

A writ of mandamus is an extraordinary remedy.4 Consequently, we will only exercise our discretion to entertain a mandamus petition when there is no “plain, speedy and adequate remedy in the ordinary course of law”5 or “there are either urgent circumstances or important legal issues that need clarification in order to promote judicial economy and administration.’ ’6 Because this case presents important choice-of-law issues that need clarification in *470order to promote judicial economy and administration, we exercise our discretion to entertain that part of the writ petition challenging the denial of GM’s and Chapman Auto’s motion to apply Arizona law.7

Since this court’s 1996 decision in Motenko, Nevada has followed the “overwhelming interest” test for resolving choice-of-law issues in tort actions. The “overwhelming interest” test can best be described as a hybrid of principles contained in the First and Second Restatements of Conflict of Laws. While this “overwhelming interest” test was intended to create a seemingly bright-line approach to resolving choice-of-law issues, it did not deviate from prior tests in a way that furthered the elusive goals of uniformity and predictability in complex, multiparty tort actions, and it fails to take advantage of the ongoing legal scrutiny by other courts and commentators given to the Second Restatement. Therefore, we conclude that our choice-of-law jurisprudence in tort actions warrants review.

Before Motenko, Nevada followed the vested rights approach

Historically, Nevada followed the First Restatement’s vested rights approach when confronted with choice-of-law issues in tort actions.8 This approach required the court to apply the “substantive law of the forum in which the injury occurred.”9 Although the application of the vested rights approach proved predictable, this court later expressed concern with the test in Motenko.10 In that case, this court abandoned the vested rights approach because that test blindly applied the substantive law of the forum where the injury occurred and produced “unjustifiably harsh results.”11

The current state of the law under Motenko

In Motenko, the plaintiff and his mother were Massachusetts residents.12 While visiting Las Vegas, the mother fell and injured herself in a hotel.13 The plaintiff then filed a claim for loss of *471parental consortium in a Nevada district court.14 The district court applied the vested rights approach and determined that Nevada law applied because the injury occurred in Nevada.15 This court agreed with the district court’s determination that Nevada law applied but did so after creating and applying the “overwhelming interest” test.16

Although a majority opinion was not reached, the Motenko court created the new “overwhelming interest” test, which retained a key feature of the vested rights approach and borrowed principles from the Second Restatement’s “most significant relationship” test.17 The Motenko test requires the trial court to apply the substantive law of the forum in tort cases unless “another state has an overwhelming interest.”18 Another state has an overwhelming interest if two or more of the Motenko factors are met.19 This approach reduces the conflict-of-law analysis in tort actions to a quantitative comparison of contacts, without any regard to a qualitative comparison of true conflicts-of-law between states.

The Motenko test is a hybrid of the vested rights approach and the most significant relationship test

Both the vested rights approach and the Motenko test start from the premise that the law of the forum governs the choice-of-law analysis in tort cases.20 Thus, both approaches emphasize a predictable and identifiable starting point that helps to further uniformity and predictability.

The Motenko test also borrowed and then modified some, but not all, of the Second Restatement’s most significant relationship test for torts.21 The Second Restatement’s most significant relationship test for torts is comprised of two sections. First, section 145(1) states that the rights and liabilities of the parties in tort *472actions are determined by the local law of the state that “has the most significant relationship to the occurrence and the parties under the principles stated in § 6.” Second, section 145(2) lists four contacts to be considered when applying the section 6 principles.22

Despite the clearly stated framework in section 145(1), the Motenko test ignores the qualitative principles in section 6, but utilizes the four quantitative contacts in section 145(2).23 The Second Restatement’s four quantitative contacts in section 145(2) were designed to play a supporting role to the primary qualitative principles of section ó.24 Thus, the Motenko test effectively reversed the clearly stated order of priority between section 6 and section 145(2) by making the section 145(2) contacts the primary inquiry. The test also ignored the application of other Restatement sections in choice-of-law determinations designed specifically for a particular tort claim. Thus, Motenko created a new, independent test that lacks the historical evaluation, and cannot benefit from ongoing legal scrutiny, to be realized from the First and Second Restatements.

The Motenko test fails to further certainty, predictability, and uniformity

The stated purpose of the Motenko test was to meet “the goal of a higher degree of certainty, predictability and uniformity of result.”25 However, as this court’s decision in Northwest Pipe Co. v. District Court26 demonstrates, the application of the Motenko test to multiparty tort actions hinders, rather than promotes, these goals.

In Northwest Pipe, the defendant, an Oregon corporation, was sued for wrongful death in Nevada by family members of individ*473uals who were killed in a California car accident. Two of the decedents were Nevada residents and four of the decedents were California residents. Nine of the eleven plaintiffs were Nevada residents with the remaining two residing in California.27

The plurality and concurrence applied the Motenko overwhelming interest test and produced an outcome in which the Nevada plaintiffs’ claims proceeded under Nevada law and the California plaintiffs’ claims against the same defendant proceeded under California law.28 Instead of qualitatively analyzing the contacts that each cause of action and party had with the competing states, the court simply counted the number of Motenko contacts each plaintiff had with California.29 While this approach may seem simplistic enough to produce uniform and predictable results, it took a plurality and a concurrence, and a dissent to determine which state’s law applied to each cause of action.

As demonstrated in Northwest Pipe, the Motenko test does not deviate from the vested rights approach in a way that furthers the goals of uniformity and predictability in complex, multiparty tort actions. Limiting an inquiry in a difficult area of law to simply counting contacts between the competing states and the parties ignores an essential part of the Second Restatement's most significant relationship test-which state has the most significant relationship to the tort and the parties? This question can be answered most effectively through the qualitative analysis framework that the most significant relationship test provides.

The Second Restatement's most significant relationship test now governs tort actions in Nevada

We take this opportunity to clarify Nevada’s choice-of-law jurisprudence and hold that the Second Restatement’s most significant relationship test governs choice-of-law issues in tort actions unless another, more specific section of the Second Restatement applies to the particular tort. Consequently, we overrule Motenko. While we are cognizant that choice-of-law analyses may, at times, lead to subjective results, the best approach to keeping those results uniform is to apply the law of the state that has the most significant relationship to the occurrence and the parties.30

*474The Second Restatement’s most significant relationship test begins with a general principle, contained in section 145: the rights and liabilities of parties with respect to an issue in tort are governed by the local law of the state that, “with respect to that issue, has the most significant relationship to the occurrence and the parties under the principles stated in § 6.” Section 6 identifies the following principles:

(1) A court, subject to constitutional restrictions, will follow a statutory directive of its own state on choice of law.

(2) When there is no such directive, the factors relevant to the choice of the applicable rule of law include

(a) the needs of the interstate and international systems,

(b) the relevant policies of the forum,

(c) the relevant policies of other interested states and the relative interests of those states in the determination of the particular issue,

(d) the protection of justified expectations,

(e) the basic policies underlying the particular field of law,

(f) certainty, predictability and uniformity of result, and

(g) ease in the determination and application of the law to be applied.

These principles are not intended to be exclusive and no one principle is weighed more heavily than another.31

Importantly, section 145 is a general statement and will not apply to all tort actions. As the dissent in Northwest Pipe noted, the Second Restatement has developed other sections that specifically apply to certain torts.32 Thus, the Second Restatement is designed to provide a particular framework depending on the nature of the tort.

Section 146 of the Second Restatement governs personal injury claims

The nature of the current claim is one for personal injury. Section 146 of the Second Restatement provides a particularized framework for analyzing choice-of-law issues in personal injury cases. Section 146 states that the rights and liabilities of the parties are governed by the “local law of the state where the injury occurred” unless “some other state has a more significant relationship” to the occurrence under the principles stated in section 6.

*475The general rule in section 146 requires the court to apply the law of the state where the injury took place. We conclude that in order for the analysis to move past this general rule and into the section 6 principles, a party must present some evidence of a relationship between the nonforum state, the occurrence giving rise to the claims for relief, and the parties. If no evidence is presented, then the general rule of section 146 governs. However, if a party does present evidence of a relationship between the nonforum state, the occurrence giving rise to the claims for relief, and the parties, then the analysis moves to an evaluation of that evidence under the section 6 principles to determine which state has a more significant relationship to the occurrence and the parties.

The section 6 factors inject flexibility into the choice-of-law analysis. Unlike the vested rights approach and the quantitative focus of the Motenko approach, an analysis of the section 6 factors considers the “content of and the policies behind the [forum and nonforum state’s] competing internal laws.”33 This is the crux on which an informed decision rests its reasoning. The Motenko dissent recognized this principle, stating that “[a] qualitative evaluation under the most significant relationship doctrine promotes consideration of differing state policies and interests underlying the particular issue as factors for making the choice-of-law decision.”34

Nevada law applies to Simmons’ causes of action against GM

GM has failed to present any evidence demonstrating that Arizona has a relationship to the occurrence giving rise to Simmons’ claims for relief against GM. The car accident occurred in Nevada, and Nevada is the place of the injury. Additionally, GM is a Delaware corporation with its principal office located in Michigan. GM manufactured the 1996 Chevrolet Metro outside Arizona’s borders. While a GM car was sold in Arizona to an Arizona resident, Chapman Auto, which is located in Arizona, is not a dealer or in any other way affiliated with GM.

Because Simmons’ claims for relief against GM are centered in Nevada where the accident occurred and Michigan where the car was manufactured, and GM has no relationship with Arizona, GM has failed to present any evidence to suggest that the general rule under section 146 should not apply. Thus, Nevada law applies to *476Simmons’ claims against GM because Nevada is the place where the injury occurred.

Arizona law applies to Simmons’ causes of action against Chapman Auto

Conversely, Chapman Auto has presented evidence demonstrating that Arizona has some relationship to the occurrence giving rise to Simmons’ claims against Chapman Auto. Chapman Auto is an independent auto dealer located in Arizona and Simmons is an Arizona resident. Chapman Auto sold the Chevrolet Metro to Simmons in Arizona. Simmons is suing Chapman Auto for injuries resulting from the failure of a roof assembly in a vehicle sold in Arizona. If Chapman Auto is found liable, the occurrence giving rise to liability will have occurred in Arizona.

Thus, the inquiry moves beyond the general rule in section 146 and into an analysis under the section 6 principles to determine whether Arizona or Nevada has a more significant relationship to Simmons, Chapman Auto, and the sale of the vehicle.35 Applying the section 6 principles, Arizona has a more significant relationship to Chapman Auto and Simmons than Nevada.

Section 6(2) (c)

Section 6(2)(c) states that ‘ ‘the relevant policies of other interested states and the relative interests of those states in the determination of the particular issue” should be considered. Unlike Nevada, Arizona has made a policy choice to allow comparative fault defenses to strict liability claims where product misuse is asserted as a defense.36 Here, there is an allegation that Simmons was driving in excess of the speed limit. If this allegation is proven true, then Arizona has an interest in seeing that its car dealers who operate solely in Arizona receive some protection in strict liability claims.

Further, Arizona’s comparative fault defense to tort actions differs from Nevada’s.37 Arizona permits recovery by a plaintiff who is found by a jury to be greater than 50% comparatively at fault, where Nevada does not.38 In such a case, Arizona only reduces the *477recovery by the percentage of comparative fault. Therefore, Arizona has made a policy decision to provide some compensation to plaintiffs regardless of their percentage of comparative fault.

In contrast, Nevada has made policy decisions to allow plaintiffs in strict liability actions to recover the full amount of their injuries regardless of fault but to prevent recovery by plaintiffs on other tort theories if their comparative fault exceeds 50%. Further, Nevada has an interest in protecting tourists who travel its roads. While these policies are indeed important, they carry less weight when they are being applied to an individual with little contact with Nevada who is seeking damages from a resident of the nonforum state for claims that arose out of that state. Thus, on balance, Arizona’s interest in having its law applied to the causes of action that an Arizona resident plaintiff raised against an Arizona car dealer outweighs Nevada’s interest in applying its own law.

Section 6(2) (d) and (f)

Section 6(2)(d) states that another factor relevant to a choice-of-law analysis is ‘ ‘the protection of justified expectations.’ ’ As previously stated, the relationship between Simmons and Chapman Auto is centered in Arizona. When Simmons purchased the car from Chapman Auto, the parties were justified in expecting that the relationship would be governed by Arizona law. Both parties were domiciled in Arizona and the transaction occurred in Arizona. Moreover, protection of this justified expectation furthers the section 6(2)(f) considerations of “certainty, predictability and uniformity of result.” Thus, the protection of both parties’ justified expectations, along with considerations of certainty, predictability, and uniformity of results, weigh in favor of applying Arizona law.39

Section 6(2) (g)

Lastly, section 6(2)(g) recommends that the courts consider the “ease in the determination and application of the law to be applied.” The analysis so far produces an outcome resulting in two separate state laws being applied to a single trial. But in this case, *478both states’ laws can be accommodated by jury instructions that explain the law applicable to each defendant with respect to Simmons’ claims and any potential comparative fault defenses to those claims. Additionally, the district court can utilize special verdict forms to guide the jury in making its determination. Thus, this consideration does not counsel against instructing the jury on two separate state laws.

We conclude, therefore, that Arizona law applies to the causes of action alleged against Chapman Auto because Arizona has a more significant relationship to the claims for relief, Simmons, and Chapman Auto than Nevada.40

CONCLUSION

We now hold that in Nevada, section 145 of the Second Restatement governs choice-of-law issues in tort actions unless the Second Restatement contains a section that specifically addresses a particular tort. Because section 146 governs choice-of-law issues in personal injury claims, we apply the most significant relationship test set forth in section 146 to this case.

Applying section 146, we deny the petition as to GM because, as a legal matter, the car accident and GM have no relationship with Arizona. Consequently, Nevada law applies to Simmons’ claims for relief asserted against GM. However, we grant the petition as to Chapman Auto because Arizona has a more significant relationship to Simmons, Chapman Auto, and the sale of the vehicle. Consequently, Arizona law applies to Simmons’ claims for relief asserted against Chapman Auto. We deny the petition with respect to the district court’s refusal to dismiss the underlying action on forum non conveniens grounds. Accordingly, we direct the clerk of this court to issue a writ of mandamus directing the district court to apply Arizona law to Simmons’ claims for relief against Chapman Auto.

Rose, C. J., Becker, Gibbons, Douglas and Parraguirre, JJ., concur.

concurring in part and dissenting in part:

I agree with the adoption of the Second Restatement as a reasonable construct for resolving conflict of law disputes. I would, however, apply Nevada law to both defendants.

9.3 The Erie Doctrine - Vertical Choice of Law in U.S. Federal Courts 9.3 The Erie Doctrine - Vertical Choice of Law in U.S. Federal Courts

9.3.1 Background on the Erie Doctrine 9.3.1 Background on the Erie Doctrine

The Erie doctrine brings together two issues: What substantive law should a federal court apply when deciding a diversity case to which no statute applies, and what procedures should it follow? You will see that the answer to both of these questions changed in the late 1930s, in part because of the Erie case itself. Erie is referred to a 'vertical' choice of law because it involves a choice between a federal rule and a state rule, requiring a court to choose not between horizontal rivals but between different levels of government.

Governing Law.

First, let's be clear about a foundational issue that sometimes gets overlooked - the issue faced in Erie arose because no federal or state statute applied. Under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, any valid federal statute would override any state rule. At the time of Erie, the law already was (as it remains) that state statutes and Constitutional provisions that apply in state court also apply and are controlling law in a diversity case in federal court. As you will see in Erie, there was no state statute on point, so the courts involved were looking to judge-made, common law.

The rule that applied before Erie came from the case of Swift v. Tyson, 41 U.S. 1 (1842). As with Erie, this case involved interpreting and applying one of the earliest federal statutes, the Rules of Decision Act (Section 34 of the Judiciary Act of 1789). The statute provided that: “The laws of the several states, except where the Constitution, treaties or statutes of the United States shall otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in trials at common law in the courts of the United States in cases where they apply.”

The central question in both Erie and Swift v. Tyson was the scope of “laws of the several states”. Did the “laws” refer only to state constitutions and statutes? Were the decisions of state court within the meaning of “laws of the several states”? Put differently, was common law as applied by the courts of the state included, or only codified rules such as statutory and constitutional law?

In between the two cases a shift occurred in the general understanding of what it is courts are about when they establish precedents. At the time of Swift v. Tyson, a court operating in a common law setting might view itself as not creating law, but as discovering law. The law could be viewed as a thing apart, determinable from the operation of logic from first principles. This, in fact, was precisely the view expressed by the Swift v. Tyson court:

It is, however, contended that the 34th section of the judiciary act of 1789, ch. 20, furnishes a rule obligatory upon this court to follow the decisions of the state tribunals in all cases to which they apply. That section provides

that the laws of the several states, except where the constitution, treaties or statutes of the United States shall otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision, in trials at common law, in the courts of the United States, in cases where they apply.

In order to maintain the argument, it is essential, therefore, to hold that the word "laws" in this section includes within the scope of its meaning the decisions of the local tribunals. In the ordinary use of language, it will hardly be contended that the decisions of courts constitute laws. They are, at most, only evidence of what the laws are, and are not, of themselves, laws. They are often reexamined, reversed and qualified by the courts themselves whenever they are found to be either defective or ill-founded or otherwise incorrect. The laws of a state are more usually understood to mean the rules and enactments promulgated by the legislative authority thereof, or long-established local customs having the force of laws. In all the various cases which have hitherto come before us for decision, this court have uniformly supposed that the true interpretation of the 34th section limited its application to state laws, strictly local that is to say, to the positive statutes of the state, and the construction thereof adopted by the local tribunals, and to rights and titles to things having a permanent locality, such as the rights and titles to real estate and other matters immovable and intraterritorial in their nature and character. It never has been supposed by us that the section did apply, or was designed to apply, to questions of a more general nature, not at all dependent upon local statutes or[p19] local usages of a fixed and permanent operation, as, for example, to the construction of ordinary contracts or other written instruments, and especially to questions of general commercial law, where the state tribunals are called upon to perform the like functions as ourselves that is, to ascertain, upon general reasoning and legal analogies, what is the true exposition of the contract or instrument, or what is the just rule furnished by the principles of commercial law to govern the case. And we have not now the slightest difficulty in holding that this section, upon its true intendment and construction, is strictly limited to local statutes and local usages of the character before stated, and does not extend to contracts and other instruments of a commercial nature, the true interpretation and effect whereof are to be sought not in the decisions of the local tribunals, but in the general principles and doctrines of commercial jurisprudence. Undoubtedly the decisions of the local tribunals upon such subjects are entitled to, and will receive, the most deliberate attention and respect of this court, but they cannot furnish positive rules or conclusive authority by which our own judgments are to be bound up and governed.

By the time Erie was decided the philosophical conception of what it is courts do had undergone a substantial change. Under the influence of legal realism and the legal positivists, it came to be accepted that judges did indeed make law and that cases were not just evidence of some hidden body of law but the law itself. Put differently, courts were recognized to be law-making bodies, not just law applying bodies, and judge-made law was understood to be law as much as any other law. Against this changed background, Erie arose.

It wasn't just changes in philosophy that led to Erie, however. A series of cases revealed how applying different law in state and federal court created opportunities for forum selection (aka forum shopping) that made the merits secondary to procedural maneuvering.

One noteworthy case was Black & White Taxicab Co. v. Brown & Yellow Taxicab Co., 276 U. S. 518 (1928). In that case, Brown & Yellow Taxicab wanted to enter into an exclusive contract with the L&N Railroad to be the only cab company that could solicit business at the L&N railroad station in Bowling Green, Kentucky. The problem was, such agreements were illegal under Kentucky common law, meaning that if the agreement was challenged in Kentucky state court it would be invalidated. Brown & Yellow then reincorporated in Tennessee. This created diversity jurisdiction for a lawsuit between Brown & Yellow and its rival, Black & White. Brown & Yellow then brought suit in federal court to prevent Black & White from interfering with its exclusive agreement. Because federal common law did not prohibit these kinds of agreements, Brown & Yellow won at trial, on appeal, and at the Supreme Court. The outcome of the case depended entirely on which court the lawsuit proceeded, state or federal, and moving the place of incorporation of a local taxicab company to a neighboring state allowed an agreement that violated the laws of the host state to be upheld.

In an influential dissent, Justice Holmes took issue with the result. In part, he challenged the idea that common law was a unified, 'transcendental' body of law.

If there were such a transcendental body of law outside of any particular State but obligatory within it unless and until changed by statute, the Courts of the United States might be right in using their independent judgment as to what it was. But there is no such body of law. The fallacy and illusion that I think exist consist in supposing that there is this outside thing to be found.

Holmes's dissent was to prove influential in Erie, as you will see.

Procedure: The background of the Rules Enabling Act

For the first 150 years of the republic, the US federal courts relied on the procedural rules of the states in which they sat, which was known as the “conformity principle”. The enactment of the Rules Enabling Act on June 19, 1934, was a revolution in the development of civil procedure in the United States. The Rules Enabling Act allowed the creation of a uniform federal system of procedure, merging both law and equity in the federal courts.

The Rules Enabling Act came near the end of a decades-long effort to reform procedure in federal courts in particular and US courts in general. Both common law writs and reform codifications were seen to be prone to manipulation on technical grounds, leading to results not based on justice. The Rules were in a large part an effort to get beyond a "sporting theory of justice" and to a system where the results conformed with the facts and the governing substantive law.

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which provide a uniform system of procedure for the federal courts, were adopted by the Supreme Court in 1937 and became effective in 1938. The Federal Rules were promulgated based on the authority delegated to the Supreme Court by the Rules Enabling Act. The process of passing the rules can be simplified as follows: first, a committee of academics, lawyers and judges proposed the rules (and today, changes to the rules), then the. Supreme Court reviews and if they approve, send the rules to Congress. The final step is Congress’s approval to allow the rules to take effect.

The Rules were still new when Erie came to the Court.

So, as you read Erie, think for a moment about the experienced federal practitioner in 1938. This practitioner would need to be an expert in the state procedural code, which was being replaced by the new Federal Rules of Civil Procedure with regard to practice in federal court. Such a practitioner also needed to be a master of federal general common law, which often provided the rule of decision in federal court. After you finish Erie, think of what of the expertise that mattered in federal court in 1937 was still going to matter in 1939.

9.3.2 Article VI, Section 2 - The Supremacy Clause 9.3.2 Article VI, Section 2 - The Supremacy Clause

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

9.3.3 The "Rules of Decision Act" - 28 U.S. Code § 1652 - State laws as rules of decision 9.3.3 The "Rules of Decision Act" - 28 U.S. Code § 1652 - State laws as rules of decision

This is the current version of the Rules of Decision Act, modified slightly but not materially from the version at issue in Erie.

The laws of the several states, except where the Constitution or treaties of the United States or Acts of Congress otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in civil actions in the courts of the United States, in cases where they apply.

9.3.4 From the Rules Enabling Act: 28 U.S.C. § 2072. Rules of procedure and evidence; power to prescribe 9.3.4 From the Rules Enabling Act: 28 U.S.C. § 2072. Rules of procedure and evidence; power to prescribe

(a) The Supreme Court shall have the power to prescribe general rules of practice and procedure and rules of evidence for cases in the United States district courts (including proceedings before magistrate judges thereof) and courts of appeals.

(b) Such rules shall not abridge, enlarge or modify any substantive right. All laws in conflict with such rules shall be of no further force or effect after such rules have taken effect.

(c) Such rules may define when a ruling of a district court is final for the purposes of appeal under section 1291 of this title.

9.3.5 Erie Railroad v. Tompkins 9.3.5 Erie Railroad v. Tompkins

ERIE RAILROAD CO. v. TOMPKINS.

No. 367.

Argued January 31, 1938.

Decided April 25, 1938.

*65Mr. Theodore Kiendl, with whom Messrs. William C. Cannon and Harold W. Bissell were on the brief, for petitioner.

*68Mr. Fred H. Rees, with whom Messrs. Alexander L. Strouse and William Walsh were on the brief, for respondent.

delivered the opinion of the Court.

The question for decision is whether the oft-challenged doctrine of Swift v. Tyson1 shall now be disapproved.

Tompkins, a citizen of Pennsylvania, was injured on a dark night by a passing freight train of the Erie Railroad Company while walking along its right of way at Hughestown in that State. He claimed that the,accident occurred through negligence in the operation, or maintenance, of the train; that h.e was rightfully on the premises as licensee because on a commonly used beaten: footpath which rah for a short distance alongside the tracks; and that he was struck by something which looked like a door projecting from one of the moving cars. To enforce that claim he brought an action in the federal court for southern New York, which had jurisdiction because the company is a corporation of that State. It denied liability; and the case was tried by a jury.

*70The Erie insisted that its duty to Tompkins was no greater than that , owed to a trespasser. It contended, among other things, that its duty to Tompkins, and hence its liability, should be determined in accordance with the Pennsylvania law;,that under the law of Pennsylvania, as declared by its highest' court, persons who use pathways along the railroad right of way — that is a longitudinal pathway as distinguished from a crossing — are to be deemed trespassers; and that the railroad is not liable for injuries to undiscovered trespassers resulting from its negligence, unless it be wanton or wilful. Tompkins denied that any such rule had been established by the decisions of the Pennsylvania courts; and contended that, since there was no statute of the State on the subject, the railroad’s duty and liability is to be determined in federal courts as a matter of general law.

.. The trial judge refused to rule that the applicable law precluded recovery. The jury brought in a verdict of $30,000; and the judgment entered thereon was affirmed by the Circuit Court of Appeals, which held, 90 F. 2d 603, 604, that it was unnecessary to consider whether the law of Pennsylvania was. as contended, because the question was one not of local, but of general, law and that “upon questions of general law the federal courts are free, in the absence of a local statute, to exercise their independent judgment as to what the law is; and it is well settled that the question of the responsibility of a railroad for injuries caused by its servants is one of general law. . . . Where the public has made open and notorious use of a railroad right of way for a long period of time and without objection, the company owes to persons on such permissive pathway a duty of care in the operation of its trains. ... It is likewise generally recognized law that a jury may find that negligence exists toward a pedestrian using a permissive path on the railroad right of way if he is hit by some object projecting from the side of the train.”

*71The Erie had contended that application of the Pennsylvania rule was required, among other things, by § 34 of the Federal Judiciary Act of September 24, 1789, c. 20, 28 U. S. C. § 725, which provides:

“The laws of the several States, except where the Constitution, treaties, or statutes of the -United States otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in trials at common law, in the courts of the United States, in cases where they apply.”

Because of the importance of the question whether the federal court was .free to disregard the alleged rule of the Pennsylvania common law, we granted certiorari.

First. Swift v. Tyson, 16 Pet. 1, 18, held that federal courts exercising jurisdiction on the ground of diversity of citizenship need not, in matters of general jurisprudence, apply the unwritten law of the State as declared by .its highest court; that they are free to exercise an independent judgment as to what the common law of the State is — or should be; and that, as there stated by Mr. Justice Story:

“the true interpretation of the thirty-fourth section limited its application to state laws strictly local, that is to say, to the positive statutes of the state, and the construction thereof adopted by the local tribunals, and to rights and titles to things having a permanent locality, such as the rights and titles to real estate, and other matters immovable and intraterritorial in their nature and character. It never has been supposed by us, that the section did apply, or was intended to apply, to questions of a more general nature, not at all dependent upon local statutes or local usages of a fixed and permanent operation, as, for example, to the construction of ordinary contracts or other written instruments, and especially to questions of general commerbial law, where the state tribunals are called upon to perform the like functions as ourselves, that is, to' ascertain upon general reasoning and legal analogies, what is the true exposition of the contract or *72instrument, or what is the just rule furnished by the principles of commercial law to govern the case.”

The Court in applying the rule of § 34 to equity cases, in Mason v. United States, 260 U. S. 545, 559, said: “The statute, however, is merely declarative of the rule which would exist in the absence of the statute.” 2 The federal courts assumed, in' the broad field of “general law,” the power to declare rules of decision which Congress was confessedly without power to enact as statutes. Doubt was repeatedly expressed as'to the correctness of the construction given § 34,3 and as to the soundness of the rule which it introduced.4 But it was the more recent research of a competent scholar, who . examined the original document, which established that the construction given to it by the Court was erroneous; and that the purpose of the section was merely to make certain that, in all matters except those in which some federal law is controlling, *73the federal courts exercising jurisdiction in diversity of citizenship cases would apply as their rules of decision the law of the State, unwritten as well as written.5

Criticism of the doctrine became widespread after the decision of Black & White Taxicab Co. v. Brown & Yellow Taxicab Co., 276 U. S. 518.6 There, Brown and Yellow, a Kentucky corporation owned by Kentuckians, and the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, also a Kentucky corporation, wished that the former should have the exclusive privilege of soliciting passenger and baggage transportation at the Bowling Green, Kentucky, railroad station; and that the Black and White, a competing Kentucky corporation, should be prevented from interfering with that privilege. Knowing that such a contract would be void under the common law of Kentucky, it was arranged that the Brown and Yellow reincorporate under the law of Tennessee, and that the contract with the railroad should be executed there. The suit was then brought by the Tennessee corporation in the federal court for western Kentucky to enjoin competition by the Black and White; an injunction issued by the District Court *74waa sustained lay the Court of Appeals; and this Court, citing many decisions in which the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson had been applied, affirmed the decree.

Second. Experience in applying the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson, had revealed its defects, political and social; and the benefits expected to flow from the rule did not accrue. Persistence of state courts in their own opinions on questions of common law prevented uniformity;7 and the . impossibility of discovering a satisfactory line of demarcation between the province of general law and that of local law developed a new well of uncertainties.8

On the other, hand, the mischievous results of the doctrine had becoihe apparent: Diversity of citizenship jurisdiction was conferred in order to prevent apprehended discrimination in state courts against those not citizens of the State. Swift v. Tyson introduced grave discrimination ’by non-citizens against citizens. It made rights enjoyed under the unwritten “general law” vary according to whether enforcement was sought in the state *75or in the federal court; and the privilege of selecting the court in which the right should be determined was conferred upon the non-citizen.9 Thus, the doctrine rendered impossible equal protection of the law. In attempting to promote uniformity of law throughout the United States^ the doctrine had prevented uniformity in the administration of the law of the State.

The discrimination resulting became in practice far-reaching. This resulted in part from the broad province accorded to the so-called “general law” as to which federal courts exercised an independent judgment.10 In addition to questions of purely commercial law, “general law” was held to include the obligations under'contracts entered into and to be performed within the State,11 the extent to which a carrier operating within a State may stipulate for exemption from liability for his own negligence -or that of his employee;12 the liability for torts committed within the State upon persons resident or property located there, even where the question of liar *76bility depended upon the scope of a property right conferred by the State;13 and the right to exemplary or punitive damages.14 Furthermore, state decisions construing local deeds,15 mineral conveyances,16 and even devises of real estate17 were disregarded.18

In part the discrimination resulted from the wide range of persons held entitled to avail themselves of the federal rule by resort to the diversity of citizenship jurisdiction. Through this jurisdiction individual citizens willing to remove from their own State and' become citizens of another might avail themselves of the federal rule.19 And, without even change of residence, a corporate citizen of *77the State could avail itself of the federal rule by re-incorporating under the laws of another State, as was done in the Taxicab case.

The injustice and confusion incident to the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson have been repeatedly urged as reasons for abolishing or limiting diversity of citizenship jurisdiction.20 Other legislative relief has been proposed.21 If only a question of statutory construction were involved, we should not be prepared to abandon a doctrine so widely applied throughout nearly a century.22 But the uncon*78stitutionality of the course pursued has now been made clear and compels us to do so.

Third. Except in matters governed by the Federal Constitution or by Acts of Congress, the law to be applied in any case is the law of the State. And whether the law of the State shall be declared by its Legislature in a statute or by its highest court in a decision is not a matter of federal concern. There is no federal general common law. Congress has no power to declare substantive rules of common law applicable in a State whether they be local in their nature or “general,” be they commercial law or a part of the law of torts. And no clause-in the Constitution purports to confer such a power upon the federal courts. As stated by Mr. Justice Field when protesting in Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. v. Baugh, 149 U. S. 368, 401, against ignoring the Ohio common law of fellow servant liability:

“I am aware that what has been termed the general law of the country — which is often little less than what the judge advancing the doctrine thinks at the time should be the general law on a particular subject — has been often advanced in judicial opinions of this court to control a . conflicting law of a State., I admit that learned judges have fallen into the habit1 of-repeating this doctrine as a convenient mode of brushing aside the law of a State in conflict with their views. And I confess that, moved and governed by the authority of the great names of those judges, I have, myself, in many instances, unhesitatingly and confidently, but I think now-erroneously, repeated the same doctrine. But, notwithstanding the great names which may be cited in favor of the doctrine, and notwithstanding the frequency with which the doctrine has been reiterated, there stands, as a perpetual protest against its repetition, the Constitution of the United States, which recognizes and preserves the autonomy and independence , of the States — independence in their legislative and inde*79pendence in their judicial departments. Supervision over either the legislative or the judicial action of the States is in no case permissible except as to matters by the Constitution specifically authorized or delegated to the United States. Any interference with either, except as thus permitted, is an invasion of the authority of the State and, to that extent, a denial of its independence.”

The fallacy underlying the rule declared in Swift v. Tyson is made clear by Mr. Justice Holmes.23 The doctrine rests upon the assumption that there is “a transcendental body of law outside of any particular State but obligatory within it unless and until changed by statute,” that federal courts have the power to use their judgment as to what the rules of common law are; and that in the federal courts “the parties are entitled to an independent judgment on matters of general law "—:

“but law in the sense in which courts speak of it today does not exist without some definite authority behind it. The common law so far as it is enforced in a State, whether called common law or not, is not the common law generally but the law of that State existing by the authority of that State without regard to what it may .have been in England or anywhere else. . . .

“the authority and only authority is the State, and if that be so, the voice adopted by the State as its own [whether it be of its Legislature or of its Supremé Court] should utter the last word.”

Thus the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson is, as Mr. Justice Holmes said, “an unconstitutional assumption of powers by courts of the United States which no lapse of time or respectable array of opinion should make us hesitate to correct.” In disapproving that doctrine we do not hold *80unconstitutional § 34 of the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789 or any other Act of Congress. We merely declare that in applying the doctrine this Court and the lower courts have invaded rights whicíi in our opinion are reserved by the Constitution to the several States.

Fourth. The defendant contended that by the common law of Pennsylvania as declared by its highest court in Falchetti v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 307 Pa. 203; 160 A. 859, the only duty owed to the plaintiff was to refrain from wilful or wanton injury. The plaintiff denied that such is the Pennsylvania law.24 In support of their respective contentions the parties discussed and cited many decisions of the Supreme Court of the State. The Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the question of liability is one of general law; and on thjat ground declined to decide the issue of state law. As. we hold this was error, the judgment is reversed and the case remanded to it for further proceedings in conformity with our opinion.

Reversed.

Mr. Justice Cardozo took no part in the consideration or decision of this case.

The case presented by the evidence is a simple one. Plaintiff was severely injured in Pennsylvania. While walking on defendant’s right of way along a much-used path at the end of the cross ties of its main track, he came into collision with an open door swinging from the side of a car in a train going in the opposite direction. Having been warned by whistle and headlight, he saw the locomo*81tive approaching and had time and space enough to step aside and so avoid danger. To justify his failure to get out of the way, he says that upon many other occasions he had safely walked there while trains'passed.

Invoking jurisdiction on the ground of. diversity of citizenship, plaintiff, a citizen .and resident of Pennsylvania, brought this suit to recover damages against, defendant, a New York corporation, in the federal court for the southern district of that State. The issues were whether negligence of defendant was a proximate cause of his injuries and whether negligence of plaintiff contributed. He claimed that, by hauling the car with the open door, defendant violated a duty to him. The defendant insisted that it violated no duty and that plaintiff’s injuries were caused by his own negligence. ..The jury gave him a verdict on which the trial court entered judgment; the circuit court of appeals affirmed. 90 F. (2d) 603.

Defendant maintained, citing Falchetti v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 307 Pa. 203; 160 A. 859, and Koontz v. B. & O. R. Co., 309 Pa. 122; 163 A. 212, that the only duty owed plaintiff was to refrain from willfully or wantonly injuring him; it argued that the courts of Pennsylvania had so ruled with respect to persons using a customary longitudinal path, as distinguished from one crossing the track. The plaintiff, insisted that the Pennsylvania decisions did not establish the rule for which the defendant contended.. Upon that issue the circuit court of appeals said (p. 604): “We need hot go into this' matter since the defendant concedes that the great weight of authority in other states is' to the contrary.- This concession is fatal to its contention, for upon questions of general law the federal courts are. free, in absence of a local statute, to exercise their independent judgment as to what the law is; and it is well settled that the question of the responsibility of a railroad for injuries caused by its servants is one of general law.” *82Upon that basis the court held the evidence sufficient to sustain a finding that plaintiff’s injuries were caused by the negligence of defendant. It also held the question of contributory negligence one for the jury.

Defendant’s petition for writ of certiorari presented two questions: Whether its duty toward plaintiff should have been determined in accordance with the law as found by the highest court of Pennsylvania, and whether the evidence conclusively showed plaintiff guilty of contributory negligence. Plaintiff contends that, as always heretofore held by this Court, the issues of negligence and contributory negligence are to be determined by general law against which local decisions may not be held conclusive; that defendant relies.on a solitary Pennsylvania case of doubtful applicability and that, even jtf the decisions of'the courts of that State were deemed controlling, the same result would have to be reached.

No constitutional question was suggested or argued below or here. And as a general rule, this Court will not consider any question not raised below and presented by the petition. Olson v. United States, 292 U. S. 246, 262. Johnson v. Manhattan Ry. Co., 289 U. S. 479, 494. Gunning v. Cooley, 281 U. S. 90, 98. Here it does not decide either of the questions presented but, changing the rule of decision in force since the foundation of the Government, remands the case td be adjudged according to a standard never before deemed permissible.

The opinion just announced states that “the question for decision is whether the oft-challenged doctrine of Swift v. Tyson [1842, 16 Pet. 1] shall now be disapproved.”

That case involved the construction of the Judiciary Act of 1789, § 34: “The laws of the several states, except where the Constitution, treaties, or statutes of the. United States otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in trials at common law in the courts of-*83the United States in cases where they apply.” Expressing the view of all the members of the Court, Mr. Justice Story said (p. 18): “In the ordinary use of language it will hardly be contended that the decisions of Courts constitute laws. They are, at most, only evidence of what- the laws are, and not. of themselves laws. They are often re-examined, reversed, and qualified by the Courts themselves, whenevér they are found to be either defective, or ill-founded, or otherwise incorrect. The laws of a -state are more usually understood to mean, the rules and enactments promulgated by the legislative authority thereof, or long established local customs having the force of laws. In all the various cases, which have hitherto come before us for decision, this Court have uniformly supposed, that the true interpretation of the thirty-fourth section limited its application to state laws strictly local, that is to say, to the positive statutes of the state, and the construction thereof adopted by the local tribunals, and to rights and titles' to things having a permanent locality, such as the rights and titles to' real- estate, and other matters immovable and intraterritorial in their nature and character. It never has been supposed by us, that the section did apply, or was designed to apply, to questions of a more general nature, not at all dependent upon local statutes or local usages of a fixed and permanent operation, as, for example, to the construction of ordinary contracts or other written instruments, and especially to questions of general commercial law, where the state .tribunals are called upon'to perform the like functions as ourselves, that is, to ascertain upon general reasoning and legal analogies, what is the true exposition of the contract or instrument, or what is the just rule furnished by the prin-. ciples of commercial law to govern the case. And we have not now the slightest difficulty in holding., that this section, upon its true intendment and construction, is strictly limited to local statutes and local usages of the .character *84before stated, and does not extend to contracts and other instruments of a commercial nature, the true interpretation and effect whereof are to be sought, not in the decisions of the local tribunals, but in the general principles and doctrines of commercial jurisprudence. Undoubtedly, the decisions of the local tribunals upon such subjects are entitled to, and will receive, the most deliberate attention and respect of this Court; but they cannot furnish positive rules, or conclusive authority, by which our own judgments are to be bound up and governed.” (Italics added.)

The doctrine of that case has been followed by this Court in an unbroken line of decisions. So far as appears, it was not questioned until more than 50 years later, and then by a single judge.1 Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. v. Baugh, 149 U. S. 368, 390. In that case, Mr. Justice Brewer, speaking for the Court, truly said (p. 373): “Whatever differences of opinion may have been expressed, have not been on the question whether a matter of general law should be settled by the independent judgment of this court, rather than through an adherence to the decisions of the state courts, but upon the other question, whether a given matter is one of local or of general law.”

And since that decision, the division of opinion in this Court has been one of the same character as it was before. In 1910, Mr. Justice Holmes, speaking for himself and two other Justices, dissented from the holding that a *85court of the United States was bound to exercise its own independent judgment in the construction of a conveyance made before the state courts had rendered an authoritative decision as to its meaning and effect. Kuhn v. Fairmont Coal Co., 215 U. S. 349. But that dissent accepted (p. 371) as ‘‘settled” the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson, and insisted (p. 372) merely that the case under consideration was by nature and necessity peculiarly local.

Thereafter, as before, the doctrine was constantly applied.2 In Black & White Taxicab Co. v. Brown & Yellow Taxicab Co., 276 U. S. 518, three judges dissented. The writer of the dissent, Mr. Justice Holmes, said, however (p. 535): “I should leave Swift v. Tyson undisturbed, as I indicated in Kuhn v. Fairmont Coal Co., but I would not allow it to spread the assumed dominion into new fields.”

No more unqualified application of the doctrine can be found than in decisions of this Court speaking through Mr. Justice Holmes. United Zinc Co. v. Britt, 258 U. S. 268. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. v. Goodman, 275 U. S. 66, 70. Without in the slightest departing from that doctrine, but implicitly applying it, the strictnéss of the rule laid down in the Goodman case was somewhat ameliorated by Pokora v. Wabash Ry. Co., 292 U. S. 98.

Whenever possible, consistently with standards sustained by reason and authority constituting the general, law, this Court has followed applicable decisions of state courts. Mutual Life Ins. Co. v. Johnson, 293 U. S. 335, 339. See Burgess v. Seligman, 107 U. S. 20, 34. Black & White Taxicab Co. v. Brown & Yellow Taxicab Co., supra, 530. Unquestionably the issues off negligence and contributory negligence upon which decision of this case *86depends are questions of general law. Hough v. Railway Co., 100 U. S. 213, 226. Lake, Shore & M. S. Ry. Co. v. Prentice, 147 U. S. 101. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. v. Baugh, supra. Gardner v. Michigan Central R. Co., 150 U. S. 349, 358. Central Vermont Ry. Co. v. White, 238 U. S. 507, 512. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. v. Goodman, supra. Pokora v. Wabash Ry. Co., supra.

While amendments to § 34 have from time to time been suggested, the section., stands as originally enacted. Evidently Congress has intended throughout the years that the rule of decision as construed should continue to govern federal courts in trials at common law. The opinion just announced suggests that Mr. Warren’s research has established that from the beginning this Court has erroneously construed § 34. But that author’s “New Light on the History of the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789” does not purport to be authoritative and was intended to be no more than suggestive. The .weight to be given to his discovery has never been discussed at this bar. Nor does the. opinion indicate the ground, disclosed by the research. In his dissenting opinion in the Taxicab case, Mr. Justice Holmes referred to Mr., barren’s work but failed to persuade the Court that “laws” as used in § 34 included varying and possibly ill-considered rulings by the courts of á State on questions of. common law. See, e. g., Swift v. Tyson, supra, 16-17. It well may be that, if the Court should now call for argument of counsel on the basis of Mr. Warren’s research, it would adhere to the construction it has always put upon § 34-. Indeed, the opinion in this case so indicates. For it declares: “If only a question of statutory construction were involved, we should not be prepared to abandon a doctrine so widely applied throughout a century. But the unconstitutionality of the course pursued has now been made clear and compels us to do so.” This means that, so far as concerns the rule of decision now condemned, the Judiciary Act of 1789, passed to establish judicial *87courts to exert the judicial power of the United States, and especially § 34 of that Act as construed, is unconstitutional; that federal courts are now bound to follow decisions of the courts of the State in which the controversies arise; and that Congress is powerless otherwise to ordain. It is hard to foresee the consequences of the radical change so made. Our opinion in the Taxicab case cites numerous decisions of this Court which serve in part to indicate the field from which it is now intended forever to bar the federal courts. It extends to all matters of contracts and torts not positively governed by state enactments. Counsel searching for precedent and reasoning to disclose common-law principles on which to guide clients and conduct litigation are by this decision told that as to all of these questions the decisions of this Court and other federal courts are no longer anywhere authoritative.

This Court has often emphasized its reluctance to consider constitutional questions, and that legislation will not be held invalid as repugnant to the fundamental law if the case may be decided upon any other ground. In view of grave consequences liable to result from erroneous exertion of its power to set aside legislation, the Court should move cautiously, seek assistance of counsel, act only after ample deliberation, show that the question is before the Court, that its decision cannot be avoided by construction of the statute assailed or otherwise, indicate precisely the principle or provision of the Constitution held to have been transgressed, and fully disclose. the reasons and authorities found to warrant the conclusion of invalidity. These safeguards against the improvident use of the great power to invalidate legislation are so well-grounded and familiar that statement of reasons or citation of authority to support them is no longer necessary. But see e. g.: Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, 11 Pet. 420, 553; Township of Pine Grove v. Talcott, 19 Wall. 666, 673; Chicago & G. T. Ry. Co. v. Wellman, 143 U. S. 339, 345; *88Baker v. Grice, 169 U. S. 284, 292; Martin v. District of Columbia, 205 U. S. 135, 140.

So far as appears, no litigant has ever challenged the power of Congress to establish the: rule as construed. It has so long endured that its destruction now without appropriate deliberation cannot be justified. There is nothing in the opinion to suggest that consideration of any constitutional question is necessary to a decision of the case. By way of reasoning, it contains nothing that requires the conclusion reached. Admittedly,- there is no authority to support that conclusion. Against the protest of those joining in this opinion, the Court declines to assign the case for reargument. It may not justly be assumed that the labor and argument of counsel for the parties would not disclose the right conclusion and aid the Court in the statement of reasons to support it. Indeed, it would have been appropriate to give Congress opportunity to be heard before devesting it of power to prescribe rules of decision to be followed' in the courts of the United States. See Myers v. United States, 272 U. S. 52, 176.

The course pursued by the Court in this case is repugnant to the Act of Congress of August 24, 1937, 50 Stat. 751. It declares: “That whenever the constitutionality of any Act of Congress affecting the public interest is drawn in question in any court of the United States in any suit or proceeding to which the United States, or any agency thereof, or any officer or employee thereof, as such officer or employee, is not a party, the court having jurisdiction of the suit or proceeding shall certify such fact to the Attorney General. In any such case the court shall permit the United States to intervene and become á party for presentation of evidence (if evidence is otherwise receivable in such suit or proceeding) and argument upon the question of the constitutionality of such Act.. .In any such suit or proceeding the United States shall, subject to the applicable provisions of law, have all the rights of a. *89party and the liabilities of a party as to court costs to the extent necessary for a proper presentation of the facts and law relating to the constitutionality of such Act.” That provision extends to this Court. § 5. If defendant had applied for and obtained the writ of certiorari upon the claim that, as now’ held, Congress has no power to prescribe the rule of decision, § 34 as construed, it would have been the duty of thi^ Court to issue the prescribed certificate to the Attorney General in order that the United States might intervene and be heard on .the constitutional question. Within the purpose of the statute and its true intent and meaning, the constitutionality of that measure has been “drawn in question.” Congress intended to give the United States the right to be heard in every case involving constitutionality of an Act affecting ihe public interest. In view of the rule that, in the absence of chállenge of constitutionality, statutes will not here be invalidated on that ground, the Act of August 24, 1937 extends to cases where constitutionality is first “drawn’ in question” by the Court. No extraordinary or-unusual action by the Court after submission of the cause should be permitted to frustrate the wholesome purpose of that Act. The duty it imposes ought here to be willingly assumed. If it were doubtful whether this case is within the scope of the Act, the Court should give the United States opportunity to intervene and, if so advised, to present argument on the constitutional question, for undoubtedly it is one of great public importance. That would be to construe the Act according to its meaning.

The Court’s opinion in its first sentence defines the question to be whether the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson shall now be disapproved; it recites (p. 72) that Congress is without power to prescribe rules of decision that have been followed by federal courts as s, result of the construction of § 34 in Swift v. Tyson and since; after discussion, it declares (pp. 77-78) that “the unconstitutionality of the course pursued [meanin the rule of decision *90resulting from that construction] compels" abandonment of the doctrine so long applied; and then near the end' of the last page the Court states that it does not hold § 34 unconstitutional, but merely that, in applying the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson construing it, this Court and the lower courts have invaded rights which are reserved by the Constitution to the several States. But, plainly through the form of words employed, the substance of the decision appears; it strikes down as unconstitutional § 34 as construed by our decisions; it divests the Congress of power to prescribe rules to be followed by federal courts when deciding questions of general law. In that broad field it compels this and the lower federal courts to follow decisions of the courts of a particular State.

I am of opinion that the constitutional validity of the rule need not be considered, because under the law, as found by the courts of Pennsylvania and -generally throughout the country, it is plain that the evidence required a finding that plaintiff was guilty of negligence that contributed to cause his injuries and that the judgment below should be reversed upon that ground.

Mr. Justice McReynolds concurs in this opinion.

I concur in the conclusion reached in this case, in the disapproval of the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson, and in the reasoning of the majority opinion except in so far as it relies upon the unconstitutionality of the “course pursued” by the federal courts.

The “doctrine of Swift v. Tyson,” as I understand it, is that the words “the laws,” as used in § 34, line one, of the Federal Judiciary Act of September 24, 1789, do not include in their meaning “the decisions of the local tribunals.” Mr. Justice Story, in deciding that point, said (16 Pet. 19):

*91“Undoubtedly, the decisions of the local tribunals upon such subjects are entitled to, and will receive, the most deliberate attention and respect of this Court; but they cannot furnish positive rules, or conclusive authority, by which our own judgments are to be bound up and governed.”