8 Venue and Forum non Conveniens 8 Venue and Forum non Conveniens

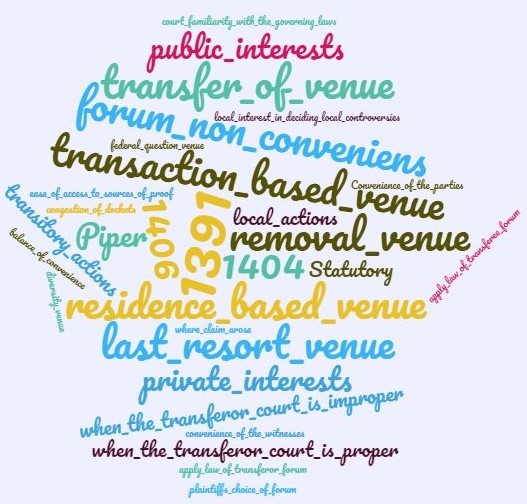

8.1 Venue and FNC Wordcloud 8.1 Venue and FNC Wordcloud

8.2 Introduction to Venue 8.2 Introduction to Venue

8.2.1 The General Federal Venue Statute, 28 U.S.C. 1391 8.2.1 The General Federal Venue Statute, 28 U.S.C. 1391

(a)Applicability of Section.—Except as otherwise provided by law—

(1) this section shall govern the venue of all civil actions brought in district courts of the United States; and

(2) the proper venue for a civil action shall be determined without regard to whether the action is local or transitory in nature.

(b) Venue in General.—A civil action may be brought in—

(1) a judicial district in which any defendant resides, if all defendants are residents of the State in which the district is located;

(2) a judicial district in which a substantial part of the events or omissions giving rise to the claim occurred, or a substantial part of property that is the subject of the action is situated; or

(3) if there is no district in which an action may otherwise be brought as provided in this section, any judicial district in which any defendant is subject to the court’s personal jurisdiction with respect to such action.

(c) Residency.—For all venue purposes—

(1) a natural person, including an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence in the United States, shall be deemed to reside in the judicial district in which that person is domiciled;

(2) an entity with the capacity to sue and be sued in its common name under applicable law, whether or not incorporated, shall be deemed to reside, if a defendant, in any judicial district in which such defendant is subject to the court’s personal jurisdiction with respect to the civil action in question and, if a plaintiff, only in the judicial district in which it maintains its principal place of business; and

(3) a defendant not resident in the United States may be sued in any judicial district, and the joinder of such a defendant shall be disregarded in determining where the action may be brought with respect to other defendants.

(d) Residency of Corporations in States With Multiple Districts.—

For purposes of venue under this chapter, in a State which has more than one judicial district and in which a defendant that is a corporation is subject to personal jurisdiction at the time an action is commenced, such corporation shall be deemed to reside in any district in that State within which its contacts would be sufficient to subject it to personal jurisdiction if that district were a separate State, and, if there is no such district, the corporation shall be deemed to reside in the district within which it has the most significant contacts.

(e) Actions Where Defendant Is Officer or Employee of the United States.—

(1) In general.—

A civil action in which a defendant is an officer or employee of the United States or any agency thereof acting in his official capacity or under color of legal authority, or an agency of the United States, or the United States, may, except as otherwise provided by law, be brought in any judicial district in which (A) a defendant in the action resides, (B) a substantial part of the events or omissions giving rise to the claim occurred, or a substantial part of property that is the subject of the action is situated, or (C) the plaintiff resides if no real property is involved in the action. Additional persons may be joined as parties to any such action in accordance with the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and with such other venue requirements as would be applicable if the United States or one of its officers, employees, or agencies were not a party.

(2) Service.—

The summons and complaint in such an action shall be served as provided by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure except that the delivery of the summons and complaint to the officer or agency as required by the rules may be made by certified mail beyond the territorial limits of the district in which the action is brought.

(f) Civil Actions Against a Foreign State.—A civil action against a foreign state as defined in section 1603(a) of this title may be brought—

(1) in any judicial district in which a substantial part of the events or omissions giving rise to the claim occurred, or a substantial part of property that is the subject of the action is situated;

(2) in any judicial district in which the vessel or cargo of a foreign state is situated, if the claim is asserted under section 1605(b) of this title;

(3) in any judicial district in which the agency or instrumentality is licensed to do business or is doing business, if the action is brought against an agency or instrumentality of a foreign state as defined in section 1603(b) of this title; or

(4) in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia if the action is brought against a foreign state or political subdivision thereof;

(g) Multiparty, Multiforum Litigation.—

A civil action in which jurisdiction of the district court is based upon section 1369 of this title may be brought in any district in which any defendant resides or in which a substantial part of the accident giving rise to the action took place.

8.2.2. 【Picture】PJ & SMJ & Venue

8.2.3 The Concept of Venue 8.2.3 The Concept of Venue

Venue Doctrine Generally. There is no Constitutional dimension to venue. It exists purely as a statutory (and, in its origins, common law) doctrine. The objective of venue doctrine is to locate litigation in a court that is convenient for all the parties. As Civil Procedure topics go, it is pretty straightforward, although a bit complicated with many small moving parts.

Venue interacts with personal jurisdiction and subject matter jurisdiction to determine in which courtroom a lawsuit can and should be heard. Personal jurisdiction, as we have seen, protects defendants from being forced to appear in locations with too slight a connection to them, and to prevent states from overreaching in ways that interfere with the sovereignty of other states. Personal jurisdiction, as you recall, is waivable by the defendant. Subject matter jurisdiction deals with whether a lawsuit belongs in federal court or state court. At its root, this doctrine is based on the Constitution’s creating a federal government of limited powers. Subject matter jurisdiction is not waivable. Both personal jurisdiction and subject matter jurisdiction have Constitutional dimensions, although both also have statutory elements. Venue, as we said, does not have a Constitutional dimension, and for our purposes is purely statutory.

Local and Transitory Actions. Section 1391 rejects making any distinction between local and transitory actions, but many states retain the distinction. Local actions generally have some connection to land - for example, a suit to determine title to land will be a local action almost anywhere, and a trespass to land remains a local action in some places. Transitory actions are everything that is not a local action. Before the statutory rejection of the doctrine, it did exist in federal courts. In one famous case, John Marshall sitting as a Circuit Judge held that Thomas Jefferson could not be sued in Virginia for a trespass to land that allegedly took place in Louisiana because it was a local action. (He couldn't be sued in Louisiana in those days, either, unless he happened to be physically present in the jurisdiction when service was attempted). Just to keep things complicated, while local actions as a matter of venue are abolished in the federal courts by § 1391, some courts view local actions as embodying a kind of subject matter jurisdiction. In those courts, only the court where the property is located has subject matter jurisdiction over local actions involving that property (this kind of subject matter jurisdiction differs somewhat from the subject matter jurisdiction of the federal courts that we just studied - both involve the power of a court to hear a kind of case, but local action subject matter jurisdiction deals with which court has the power to hear a local action, not Constitutional limits on federal power). A court viewing the local action as embodying this kind of subject matter jurisdiction issue will refuse to entertain a local action involving property not within its jurisdiction. See, Eldee-K Rental Props., LLC v. DIRECTV, Inc., 748 F.3d 943 (9th Cir. 2014). For our purposes, local versus transitory actions falls in that category of doctrine that you should have heard about but that you won't be expected to apply, especially as it no longer applies to the application of venue rules in federal court.

Venue for Diversity and Venue for Federal Questions. Venue today is determined without regard to the source of federal subject matter jurisdiction. At one time the statute drew a distinction, but not today. If you run across old cases that discuss this, remember that the source of subject matter jurisdiction does not matter today. Again, we are not going to concern ourselves with this.

Judicial Districts. You will note that the venue statute refers to judicial districts. In some smaller states - for example, Vermont - the entire state constitutes a judicial district. In larger states, such as New York, the state will be divided into districts, such as the Southern District of New York. The statute talks about districts, not states. For venue purposes, a defendant situated in the Eastern District of New York would not be analyzed exactly the same as a defendant from the Southern, Western, or Northern districts.

Districts can be subdivided into divisions within the same district. This does not bear on whether venue is proper or improper, but when we get to venue transfer it is possible to transfer a case from one division to another in the same district. This can have the effect of changing which judge hears the case, which some attorneys might hope or fear would affect the outcome.

The Basic Rule.

We are going to talk about four different ways to set venue: venue after removal from state court, residence based venue, transaction based venue, and catch all venue.

Removal venue. If a case is removed from state court, Section 1391 does not apply. Venue is proper in the court to which the case was removed. End of story. You can forget all that follows if you are dealing with a case that has been removed. Venue is proper. See generally, Wright & Miller, § 3732 Procedure for Removal—Venue in Removed Actions ("It . . . is immaterial that the federal court to which the action is removed would not have been a proper venue if the action originally had been brought there.")

Residence Venue. The first question to ask is this: are all the defendants from the same state? If they are not (disregarding defendants "not resident in the United States"), residence-based venue will not apply. If they are all from the same state, then venue will be proper in any district in which any one of the defendants resides.

Transactional Venue. Did a "substantial part of the events or omissions giving rise to the claim" occur in the district where the lawsuit was filed? If so, venue is proper there. If not, venue is not proper. Note that the statute does not say "the majority (or even plurality) of events or omissions" nor does it say "any part." In many cases, there will be more than one district where substantial acts or omissions occurred, which yields a choice between those districts. While the substantiality line is not precise, and you will need to do forum specific research if the issue is material to a case you are involved in, in general in contract cases the court is likely to look at where a contract is negotiated and where it was to be performed, and in tort cases at where any tortious acts occurred and where harm was suffered. Some courts look only to the actions of the defendants; others look to the actions of both plaintiffs and defendants in assessing substantiality. While specific personal jurisdiction and transactional venue inevitably will involve some of the same facts, it has been argued that the two are analytically distinct and should be approached individually. See generally, Wright & Miller, § 3806 Section 1391(b)(2)—Transactional Venue.

Choice of Residence and Transactional Venues. Note that plaintiffs have a choice between residence venue and transactional venue, as well as a choice among the potential venues under either of those provisions. If all the defendants, for example, are from New York (let's say five from the Eastern District and one from the Southern District), but substantial parts of the acts or omissions occurred in the Western District of Pennsylvania and also the Eastern District of Tennessee, so far as venue goes the plaintiff has a choice. On those facts, the Eastern District of New York, the Southern District of New York, the Western District of Pennsylvania, and the Eastern District of Tennessee are all proper venues. On the other hand, the Northern District of New York, the Central District of Tennessee, and the Eastern District of Pennsylvania would not be proper venues. (Can you explain why?)

Our final provision, catch all venue, only comes into play if neither transactional nor residence venue provide a proper venue.

Catch All Venue. Only if no other venue is proper do we turn to 28 U.S.C. § 1391 (b)(3), the catch all provision. If, and only if, venue is not proper under either transactional or residence venue, venue is proper in "any judicial district in which any defendant is subject to the court’s personal jurisdiction with respect to such action." Take a moment and think about when this could arise. It is certainly possible that defendants might be from different states, but how likely is it that there is no US district where a "substantial part" of the activities or omissions giving rise to the claim occurred? Not very likely for a US-based case, which suggests that catch-all venue applies mainly when the action has arisen outside the US. Note also that catch all venue provides a location where venue is proper, but personal jurisdiction still needs to addressed for each of the defendants.

Determining Residence for Venue. The rules for residence are set forth in 1391(c). For natural persons residence equals domicile. For corporations, LLCs, partnerships, labor unions, other unincorporated associations, and any other entity that can be sued under 'common name,' the test for all these different kinds of entities has us look at personal jurisdiction. For all but corporations (and probably LLCs), the test is simple, if they can be sued under their common entity name, the entity is resident in any district where personal jurisdiction exists. (There is a provision for residence for plaintiffs, which is irrelevant to 1391(b) but perhaps not to some specialized venue statutes). For corporations, and probably for LLCs despite the use of the word 'corporation' in the statute, the test gets just a little bit more complicated in multidistrict states. While personal jurisdiction is determined at a state basis, for corporations the test is further narrowed in 1391(d) to determine whether personal jurisdiction esists at a district level, and restricts residence not to the state but to the districts where the defendant's actions would make it subject to personal jurisdiction. If those contacts are enough for personal jurisdiction at a state level but not at the level of any one district, the district with the most contacts is the residence.

Residency for Resident Aliens and Defendants Not Resident in the United States. Alien corporations, like domestic corporations, reside in any district in which they are subject to personal jurisdiction. Resident aliens reside in the district where they have permanent residence. Those natural persons not resident in the United States – which includes US citizens resident abroad as well as non-resident aliens – fall under (c)(3) and venue is proper in any judicial district.

Time For Determining Venue. Proper venue is determined at the outset of the litigation.

Waiver of Venue and Forum Selection Clauses. Venue can be waived, either explicitly or by failing to assert a venue defense. Procedurally, venue is considered a privilege and an objection to venue has to be affirmatively asserted. This normally occurs through a motion under Federal Rule 12. Parties can also agree to waive venue in advance. For example, as with personal jurisdiction, parties to a contract can waive venue objections and agree to a forum where venue would not otherwise have been proper. When asked to enforce such clauses, courts will ordinarily enforce these clauses in all but the most extraordinary cases, but will nonetheless look at systemic considerations, such as whether the selected location is convenient for nonparties. See Atlantic Marine Construction Co., Inc. v. United States District Court for the Western District of Texas, 571 U.S. 49 (2013) (Granting mandamus and ordering transfer of suit pursuit under § 1404 pursuant to forum selection clause). In the same case, the Court held that the validity of the original venue is to be decided under the venue statute, without regard to the forum selection clause.

Defective Venue. When venue is improper, the court has a choice: it can dismiss the action or it can transfer the case to another federal forum where venue is proper. (In most cases in federal court it will transfer). We address that in the section that follows, where we will learn that transfer also is possible when the original venue is proper.

8.3 How to Transfer Venue 8.3 How to Transfer Venue

Within a system, cases can be transferred from one venue to another. Thus, within the federal system, a case can be transferred from one venue (say, the Northern District of Illinois) to another federal court venue (say, the Southern District of New York). This can happen when the original venue is proper or when the original venue was improper. In a given state system - say, Virginia - similar transfers can be made from one venue in that state court system to another venue in that state court system.

Transfers cannot be made from one system to another, however. A Virginia state court cannot transfer a case to a North Carolina state court, even if it finds North Carolina to be the location of proper venue. Also, there are no venue transfers between courts in state systems and courts in the federal system.

The statutes, case, and discussion below should make all this clear.

8.3.1 When the Transferor Court is Proper - 28 U.S.C. § 1404 (a) – Change of Venue 8.3.1 When the Transferor Court is Proper - 28 U.S.C. § 1404 (a) – Change of Venue

28 U.S.C. § 1404 (a) – Change of Venue

(a) For the convenience of parties and witnesses, in the interest of justice, a district court may transfer any civil action to any other district or division where it might have been brought or to any district or division to which all parties have consented.

8.3.2 When the Transferor Court is Improper - 28 U.S.C. § 1406 (a), (b) – Cure or Waiver of Defects 8.3.2 When the Transferor Court is Improper - 28 U.S.C. § 1406 (a), (b) – Cure or Waiver of Defects

28 U.S.C. § 1406 (a), (b) – Cure or Waiver of Defects

(a) The district court of a district in which is filed a case laying venue in the wrong division or district shall dismiss, or if it be in the interest of justice, transfer such case to any district or division in which it could have been brought;

(b) Nothing in this chapter shall impair the jurisdiction of a district court of any matter involving a party who does not interpose timely and sufficient objection to the venue.

8.3.3 Smith v. Yeager 8.3.3 Smith v. Yeager

Barbara SMITH and Clarence Gasby, Plaintiffs, v. Martin J.A. YEAGER, et al., Defendants.

Civil Action No. 16-554 (RBW)

United States District Court, District of Columbia.

Signed 01/13/2017

*53David Gregg Whitworth, Jr., Whitworth Smith LLC, Edgewater, MD, Wes Patrick Henderson, Henderson Law, LLC, Crof-ton, MD, for Plaintiffs.

David Drake Hudgins, Hudgins Law Firm, P.C., Alexandria, VA, for Defendants.

MEMORANDUM OPINION

The plaintiffs, Barbara Smith and Clarence A. D. Gasby, initiated this action against the defendants, Martin J. A. Yeager, Land, Carroll & Blair, P.C. (“Land Carroll”), where Yeager was a principal and agent, Gregory T. Dumont, and Mid-Atlantic Commercial Law Group, LLC (“Mid-Atlantic”), where Dumont was a principal and agent, asserting a legal malpractice claim regarding the defendants’ representation of the plaintiffs “in a landlord-tenant matter,” (the “L and T matter”) “in the Superior Court of the District of Columbia,” (the “Superior Court”). Complaint and Demand for Jury Trial (“Compl”) ¶¶1, 8-9, 14, ECF No. 1-3. Specifically, the plaintiffs allege that the defendants breached their “duty to use [the] degree of care reasonably expected of other legal professionals with similar skills acting under the same or similar circumstances” while representing them in the L and T matter in Superior Court. Id. ¶ 38. Currently before the Court is the defendants’ Motion to Transfer Venue Under 28 U.S.C. § 1404 (“Defs.’ Mot.”), which seeks to transfer this action to the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. Upon careful consideration of the parties’ submissions, the Court concludes for the following reasons that it must deny the defendants’ motion.1

I. BACKGROUND

“On February 7, 1994, the landlord for Union Station, Union Station Venture, Ltd. [ (“Union Station Venture”),] entered into a lease agreement [(“Lease”)] with La Femme Noire D.C., Incorporated [ (“La Femme Noire”) ], a District of Columbia corporation” and' subsidiary of Ark Restaurants Corporation (“Ark Restaurants”). Compl. ¶ 16. Smith, a former employee of Ark Restaurants, “signed the lease in her official capacity as an officer of *54[La Femme Noire].” Id. Four years later, La Femme Noire, as part of a “deal [that] was structured as an asset sale,” assigned its lease agreement with Union Station Venture to Finally Free, Inc. (“Finally Free”), “a Delaware corporation formed by the [plaintiffs.” Id. ¶ 17. “In or about 2007, [Union Station Venture] sold its interest in Union Station to Union Station Investco, LLC [ (“Union Station Investco”) ].” Id. ¶ 18. “Thereafter, [Finally Free] fell behind in the payment of the rent [and], on or about January 25, 2013, [Union Station Investco] filed the [L and T] matter” solely against La Femme Noire, “seeking possession of the premises on the grounds of the unpaid rent.” Id

On or about February 12, 2013, La Fem-me Noire “retained [the defendants] to provide [it] legal services” in the L and T matter. Defs.’ P. & A. at 2. La Femme Noire entered into a Representation Agreement (the “Agreement”) with Land Carroll, which outlined the terms and conditions governing the legal services that would be provided in the L and T matter. See generally Defs.’ Exhibit (“Ex.”) C (Representation Agreement (“Agreement”)). On March 21, 2013, “[u]pon information and belief [that] La Femme [Noire] ha[d] never been properly incorporated in D.C.[,] or [in] any other jurisdiction,” United Station Investco “moved to amend its complaint to add [ ] Smith and [ ] Gasby to the [L and T] matter as individual [defendants.” Compl. ¶ 20. “On April 10, 2013, in open court,” the defendants provided “the assignment documents purporting to show that the Lease was assigned to [Finally Free] in 1998, but did not demonstrate that [La Femme Noire] existed at the time the [L]ease was signed or assigned.” M. ¶ 24. Consequently, Smith and Gasby “were added as defendants to the [L and T matter].” Id. The parties dispute whether Smith and Gasby became a party to the Agreement after being named as individual defendants in the L and T matter. See Counterclaim (Mar. 29, 2016) (“Coun-tercl.”) ¶ 12, ECF No. 6 (asserting that “Gasby[ ] orally requested that [Land Ca-roll] represent” the plaintiffs “pursuant to the terms of the [ ] Agreement”); see also Pis.’ Opp’n at 5 (denying that such an oral agreement modifying the Agreement was ever made).

During the L and T pre-trial and trial proceedings, the defendants did “not provide any proof that [La Femme Noire] existed at any point” and “conceded that the corporation never existed.” Compl. ¶ 25; see also id. ¶¶ 21-30. The L and T matter “resulted in a judgment being entered personally against [the plaintiffs ... on September 19, 2013,” id. ¶ 14, and according to the plaintiffs, “[t]he sole basis to hold ... Smith and Gasby liable was the mistaken belief and concession by the [defendants that [La Femme Noire] never existed as an entity and at all times was just a name,” id. ¶ 30. Thereafter, “Smith and Gasby retained new counsel to assist them with managing various issues,” who were able to “confirm! ] that [La Femme Noire’s] Articles of Incorporation had been filed” and therefore was a valid existing entity. Id. ¶ 32. Smith and Gasby then filed “a Rule 60 motion to vacate the judgment” in the L and T matter, id. ¶ 33, for the purpose of demonstrating “that [La Fem-me Noire] in fact existed at all relevant times,” id. ¶ 34, and that they “were never in possession [of the premises] in their personal capacities and therefore there was no subject matter jurisdiction as against them in the Landlord & Tenant Branch,” id. ¶ 33. However, that motion was denied. See id. ¶ 34.

On January 22, 2016, Smith and Gasby initiated this legal malpractice action against the defendants in Superior Court. See Compl. The defendants then removed the plaintiffs’ case to this District pursuant *55to 28 U.S.C. § 1441(a). See Notice of Removal ¶ 5, ECF No. 1. After the case was removed to this Court, the defendants responded to the plaintiffs’ Complaint and filed a counterclaim for breach of contract based on the plaintiffs’ failure to adhere to the terms of the Agreement. See Coun-tercl. at 1. The defendants now move to transfer this case to the Eastern District of Virginia. See generally Defs.’ Mot.

II. STANDARD OF REVIEW

28 U.S.C. § 1404(a) provides that, “[f|or the convenience of parties and witnesses, in the interest of justice, a district court may transfer any civil action to any other .district or division where it might have been brought or to any district or division to which all parties have consented.” 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a) (2012). The decision to transfer a case is discretionary, and a district court must conduct “an individualized, ‘factually analytical, case-by-case determination of convenience and fairness.’ ” New Hope Power Co. v. U.S. Army Corps of Eng’rs, 724 F.Supp.2d 90, 94 (D.D.C. 2010) (quoting SEC v. Savoy Indus. Inc., 587 F.2d 1149, 1154 (D.C. Cir. 1978)). And the moving party “bears the burden of establishing that the transfer of th[e] action is proper.” Greater Yellowstone Coal. v. Bosworth, 180 F.Supp.2d 124, 127 (D.D.C. 2001) (citation omitted).

As a threshold matter, a district court must determine that the proposed transferee court is located “in a district where the action might have been brought.” Fed. Housing Fin. Agency v. First Tenn. Bank Nat’l Ass’n, 856 F.Supp.2d 186, 190 (D.D.C. 2012) (Walton, J.) (quoting Montgomery v. STG Intern., Inc., 532 F.Supp.2d 29, 32 (D.D.C. 2008)). If so, then a district court

considers both the private interests of the parties and the public interests of the courts[.] The private interest considerations include: (1) the plaintiffs’ choice of forum, unless the balance of convenience is strongly in favor of the defendants; (2) the defendants’ choice of forum; (3) whether the claim arose elsewhere; (4) the convenience of the parties; (5) the convenience of the witnesses ..., but only to the extent that the witnesses may actually be unavailable for trial in one of the fora; and (6) the ease of access to sources of proof. The public interest considerations include: (1) the transferee[] [court’s] familiarity with the governing laws; (2) the relative congestion of the calendars of the potential transferee and transfer- or courts; and (3) the local interest in deciding local controversies at home.

Shapiro, Lifschitz & Schram, P.C. v. Hazard, 24 F.Supp.2d 66, 71 (D.D.C. 1998) (citation omitted).

III. ANALYSIS

There is no dispute that this case could have been brought in the Eastern District of Virginia, as the plaintiffs are residents of New York and all of the defendants reside in Virginia, Compl. ¶¶2-7, where the proposed transferee court, the Eastern District of Virginia, is located, see 28 U.S.C. § 1391(b)(1) (“A civil action may be brought in ... a judicial district in which any defendant resides, if all defendants are residents of the State in which the district is located.”).2 Accordingly, the issues for *56the Court to assess are therefore; (1) whether the defendants are estopped from seeking a venue change after filing a counterclaim in this district; if not, (2) whether the forum-selection clause in the Agreement requires this case to be transferred to the Eastern District of Virginia; and if not, (3) whether the defendants have satisfied their burden of showing that the balancing of the private and public interest factors of § 1404(a) weighs in favor of transferring this case to the Eastern District of Virginia.

A. The Filing of a Counterclaim Does Not Prevent a Party from Seeking a Venue Change

The plaintiffs assert that the defendants “waived their ability to seek a transfer” by removing this case from Superior Court to this Court, and then filing their Counterclaim in the case, thereby “submit[ing] themselves to the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court.” Pis.’ Opp’n at 3. In response, the defendants argue that the filing of a compulsory counterclaim does not constitute a waiver of either jurisdiction or venue. See Defs.’ Reply at 4-6.

“Unlike a motion to dismiss for improper venue under Rule 12(b)(3), a motion to transfer venue under [§ ] 1404(a) is not a ‘defense’ that must be raised by pre-answer motion or in a responsive pleading.” Nichols v. Vilsack, 183 F.Supp.3d 39, 42 (D.D.C. 2016) (citing 14D Charles Alan Wright & Arthur R. Miller, Federal Practice & Procedure § 3829 (4th ed.)). This is so because “the purpose of [§ 1404(a) ] is to prevent the waste of time, energy and money and to protect litigants, witnesses and the public against unnecessary inconvenience and expense.” Intrepid Potash-New Mexico, LLC v. U.S. Dep’t of Interior, 669 F.Supp.2d 88, 92 (D.D.C. 2009) (quoting Van Dusen v. Barrack, 376 U.S. 612, 616, 84 S.Ct. 805, 11 L.Ed.2d 945 (1964)). Additionally, “[fjor a § 1404(a) motion, ‘there is no claim that venue is improper ... [and] a request to transfer [under § 1404(a) ] [is not] waived by the [defendant if not raised prior to or in a responsive pleading.’ ” Id. (quoting W. Watersheds Project v. Clarke, Civil Action No. 03-1985(HHK), slip op. at *6 n.9 (D.D.C. July 28, 2004)). Moreover, “a motion to transfer may be made at any time after the initiation of an action under [§ ] 1404(a).” Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya v. Miski, 496 F.Supp.2d 137, 140 n.3 (D.D.C. 2007) (Walton, J.).

Here, the defendants did not waive their ability to seek a transfer of venue pursuant to § 1404(a) by filing a counterclaim after this case was removed to this Court in conjunction with their answer to the plaintiffs’ Complaint. In their § 1404(a) motion, the defendants are not claiming that venue is improper in this District, and in fact, have acknowledged that venue is proper in this District. See Notice of Removal (Mar. 23, 2016), ECF No. 1, ¶¶ 4-5 (“The United States District Court for the District of Columbia has jurisdiction over this action pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1332(a), diversity jurisdiction.... Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1441(a), [the defendants are entitled to remove this action to this Court because it is the district court embracing the place where the action is currently pending.”). Rather, the defendants seek to transfer this case “[f]or the convenience of [the] parties and witnesses, [and] in the interest of justice.” Defs.’ P. & A. at 3 (citing § 1404(a)). Accordingly, because the defendants move to transfer this case pursuant to § 1404(a), which they may do “at any time after the initiation of an action,” Miski, 496 F.Supp.2d at 140 n.3, their filing of a counterclaim in this District does not prohibit them from seeking a transfer under § 1404(a).

*57B. The Agreement’s Forum Selection Clause Does Not Modify the Court’s § 1404(a) Analysis

The Agreement’s forum-selection clause provides that the parties “hereby consent to the jurisdiction of the courts of the Commonwealth of Virginia and to venue in the courts of the City of Alexandria, Virginia for purposes of resolving any disputes between the parties.”. Defs.’ Mot., Ex. C (Agreement) ¶13. The defendants argue that this case should be transferred to the Eastern District of Virginia because the forum-selection clause 'in the Agreement should be given mandatory effect, and because the plaintiffs “consented to personal jurisdiction and venue in Virginia.” Defs.’ P. & A. at 4. In response, the plaintiffs contend that they are not bound by the forum-selection clause of the Agreement because they never contracted to be parties to the Agreement in their individual capacities. Pis,’ Opp’n at 4-6. The plaintiffs also argue that, even assuming that they are bound by the terms of the Agreement, the forum-selection clause is permissive and not binding because the clause lacks “language clearly establishing exclusive jurisdiction and venue, to the exclusion of all others.” Id. at 6 (citing Byrd v. Admiral Moving & Storage, Inc., 356 F.Supp.2d 234 (D.D.C. 2005)).

The Supreme Court has made clear that § 1404(a) “provides a mechanism for enforcement of forum-selection clauses that point to a particular federal district.” Atl. Marine Constr. Co., Inc. v. U.S. Dist. Court for W. Dist. of Texas, — U.S. -, 134 S.Ct. 568, 579, 187 L.Ed.2d 487 (2013). “And as the [Supreme] Court stated, ‘[w]hen the parties have agreed to a valid forum-selection clause, a district court should ordinarily transfer the case to the forum specified in that clause,... [0]nly under extraordinary circumstances unrelated to the convenience of the parties should a § 1404(a) motion be denied.’” One on One Basketball, Inc. v. Glob. Payments Direct, Inc., 38 F.Supp.3d 44, 49 (D.D.C. 2014) (quoting Atl. Marine Constr., — U.S. -, 134 S.Ct. at 581). Furthermore, “[t]he non-movant bears the burden of demonstrating that such extraordinary circumstances, exist and must show ‘why the court should not transfer the case to the forum to which the parties agreed.’ ” McGowan v. Pierside Boatworks, Inc., 215 F.Supp.3d 48, 50, No. 16-cv-00758 (APM), 2016 WL 6088268, at *1 (D.D.C. Oct. 17, 2016) (quoting Atl. Marine Constr., — U.S. —, 134 S.Ct. at 582).

Here, the challenged . forum-selection clause does not require the Court “to-.adjust [its] usual, § 1404(a) analysis,” Atl. Marine Constr., — U.S. —, 134. S.Ct. at 581, because the record does not show that the plaintiffs, in their individual capacities, contractually agreed to be bound,by ¡the Agreement or the terms of its forum-selection clause. As the Court previously noted, the parties dispute whether the plaintiffs are parties to the Agreement. See supra Part 1 at 3. However, the Agreement, which “may not be modified except by a writing signed by each party,” Defs.’ Mot., Ex. C (Agreement) ¶ 15, . is not signed by the plaintiffs in their individual capacities., see id. (showing that the parties to the Agreement are La Femme Noire and Land Carroll), and despite the defendants’ representation that the plaintiffs “orally requested that [the defendants] represent them in their individual capacity,” see Defs.’ Mot., Ex. B (Dumont Aff.) ¶ 9, the record is devoid of any documents executed by the plaintiffs that modify the Agreement to reflect their intent to be bound by the Agreement in their individual capacities as required by the Agreement. Despite the absence of any such documentation, the defendants argue that “[w]hile Gasby may not have physically signed the Agreement, he agreed to its terms and authorized [his agent] to sign on his be*58half.” Defs.’ Reply at 2 (citing id. Ex. A (email correspondence dated February 21, 2013 (“February 21st Email”)) at 1 (“Attached please find the signed agreement that I signed on behalf of Dan Gasby.”). But, this email correspondence occurred shortly after Smith and Gasby, acting on behalf of La Femme Noire, retained Land Carroll to represent La Femme Noire in the L and T matter, see Defs.’ P. & A. at 2, and one month before the plaintiffs in that matter moved to add Smith and Gas-by as individual defendants, see Compl. ¶ 20. Additionally, Gasby has submitted an affidavit attesting that he “did not sign the [] Agreement identified by [the defendants,” nor did he “orally request, either on [his] behalf or on behalf of [] Smith, that [the defendants represent [the plaintiffs] interests under the same terms and conditions that [the defendants] had been purporting to represent La Femme Noir.” Pis.’ Opp’n, Ex. A (Affidavit of Clarence A.D. Gasby) ¶¶ 6-6. Thus, in reviewing the language found in the four corners of the Agreement, coupled with the additional evidence proffered by the parties, the Court finds that Smith and Gasby are not parties to the Agreement in their individual capacities. Accordingly, the plaintiffs are not bound by the Agreement’s forum-selection clause, and thus, that clause does not alter the Court’s § 1404(a) analysis.

C. Section 1404(a)’s Balancing Test

Now that the Court has determined that the forum-selection clause in the Agreement does not change the “calculus” of the Court’s § 1404(a) analysis, Atl. Marine Constr., — U.S. -, 134 S.Ct. at 581, the Court turns to the private and public interest factors provided in § 1404(a).

1, The Private Interest Factors

a. The Parties’ Choice of Forum and Where the Claims Arose

Generally, the plaintiffs choice of forum is given substantial deference, and therefore, the movant requesting a transfer of venue “bears a heavy burden of establishing that [the] plaintiffs’ choice of forum is inappropriate.” Thayer/Patricof Educ. Funding, L.L.C. v. Pryor Res., Inc., 196 F.Supp.2d 21, 31 (D.D.C. 2002) (citations omitted). Additionally, district courts are to defer to a plaintiffs choice of forum unless that forum has “no meaningful relationship to the plaintiffs claims or to the parties,” U.S. ex rel. Westrick v. Second Chance Body Armor, Inc., 771 F.Supp.2d 42, 47 (D.D.C. 2011), or if “most of the relevant events occurred elsewhere,” Aftab v. Gonzalez, 597 F.Supp.2d 76, 80 (D.D.C. 2009) (quoting Hunter v. Johanns, 517 F.Supp.2d 340, 344 (D.D.C. 2007)).

Here, the Court finds that the plaintiffs’ choice of forum is entitled to deference because there is a substantial nexus between this District and the factual circumstances underlying the plaintiffs’ legal malpractice allegations. The defendants devote the crux of their argument to the forum-selection clause in the Agreement. Defs.’ Reply at 6-7. However, as the Court previously concluded, the Agreement’s forum-selection clause has no bearing on its § 1404(a) analysis. See supra Part III.B. What is compelling is that the plaintiffs’ legal malpractice claim stems from the defendants’ alleged “acts or omissions made in the Landlord Tenant Branch of the Superior Court.” Pis.’ Opp’n at 9; see also Defs.’ P. & A. at 6 (noting that “the underlying dispute involves a landlord-tenant action in [ ] Superior Court”). Consequently, because the factual circumstances surrounding the plaintiffs’ legal malpractice claim arose in this District, and because the defendants have not carried their burden of demonstrating that the plaintiffs’ choice of forum is unsuitable, the Court finds that “the location where the claims arose outweighs the [defendants’] choice of *59forum and therefore weighs in favor of [not] transferring this case.” United States v. Quicken Loans, Inc., 217 F.Supp.3d 272, 278, No. 15-613 (RBW), 2016 WL 6838186, at *4 (D.D.C. Nov. 18, 2016) (Walton, J.).

b. The Convenience of the Parties and Witnesses and the Ease of Access to Sources of Proof

The defendants argue that transferring this case to the Eastern District of Virginia would promote convenience because (1) “[a]ll of the individual defendants live and work in Virginia, and the law firm defendants are Virginia businesses with them headquarters in Virginia”; (2) as “the plaintiffs reside in New York, the Eastern District of Virginia is no more inconvenient to them than [this District],” Defs.’ P. & A. at 5; and (3) “the witnesses and documents relevant in this legal malpractice case are mainly located outside of [this District],” id. at 6. In response, the plaintiffs contend that transferring the case “will merely allow the [defendants the convenience of a shorter drive to the courthouse[, which] will then result in a longer drive for [the p]laintiffs, as they will have to drive out of the District of Columbia to the City of Alexandria.” Pis.’ Opp’n at 12.

“Unless all parties reside in the selected jurisdiction, any litigation will be more expensive for some than for others.” Kotan v. Pizza Outlet, Inc., 400 F.Supp.2d 44, 50 (D.D.C. 2005) (quoting Moses v. Bus. Card Express, Inc., 929 F.2d 1131, 1139 (6th Cir. 1991)). Therefore, “for this factor to weigh in favor of transfer, litigating in the transferee district must not merely shift inconvenience to the plaintiffs, but rather should lead to an overall increase in convenience for the parties.” U.S. ex rel. Westrick, 771 F.Supp.2d at 48.

The defendants have not demonstrated that transferring the case to the Eastern District of Virginia “will lead to a net increase in convenience for all parties.” Id. While it is true that the defendants either reside or have their principal offices in Virginia and the majority of the legal work conducted in the underlying L and T matter may have occurred in Virginia, the convenience the defendants seek by transferring this case from this District to the Eastern District of Virginia is minimal and benefits only them. Other than the defendants and some other representatives who participated in the L and T matter, the plaintiffs and the other “potential witnesses will be required to travel from either New York or some other location outside the City of Alexandria.” Pis.’ Opp’n at 13 (noting that “the [plaintiffs will likely need to call non-party witnesses located within the District of Columbia as this matter relates to a case litigated in the District of Columbia that relate[s] to premises leased in the District of Columbia”). Consequently, transferring the case to the Eastern District of Virginia will only “shift inconvenience to the plaintiffs.” U.S. ex rel. Westrick, 771 F.Supp.2d at 48. Therefore, because the defendants “have not shown that transferring this case will result in more than marginal relief,” id and because this District is a more convenient forum for the plaintiffs and many of the witnesses, this factor weighs against transferring this case to the Eastern District of Virginia.

2. The Public Interest Factors

a. The Relative Congestion of the Transferee and Transferor Courts

The defendants contend that their “transfer request is not solely due to the convenience for parties and witnesses, or to obtain a procedural advantage, [but that] they also seek a speedy resolution to the litigation.” Defs.’ Reply at 7 (footnote omitted). In response, the plaintiffs assert *60that the number of filings in this District and in the Eastern District of Virginia “are arguably comparable” “[g]iven their reasonably close geographic proximity,” and thus “the balance of congestion ... remains equal.” Pis.’ Opp’n at 11.

“In this [District, potential speed of re'solutioh is examined by comparing the median filing times to disposition in the courts at issue.” Fed. Housing Fin. Agency, 856 F.Supp.2d at 194 (quoting Spaeth v. Mich. State Univ. Coll. of Law, 845 F.Supp.2d 48, 60 (D.D.C. 2012)). According to the latest statistics concerning federal judicial caseloads, the median filing-to-disposition period in this District was 8.0 months, compared to 5.2 months in the Eastern District of Virginia. U.S. District Courts—Combined Civil and Criminal Federal Court Management Statistics at 2, 25 (June 30, 2016), available at http://www. uscóürts.gov/statistics/table/na/federal-court-management-statistics/2016/06/30-1. 'Accordingly, 'the relative congestion of the Eastern District of Virginia weighs in favor of transfer to that court, but only slightly, considering that the filing-to-disposition period is not that significant.

b. The Local Interest in Deciding Local Controversies at Home

The plaintiffs argue that this District “ha[s] a greater interest than Virginia ... in litigating [this] District of Columbia legal malpractice action” because their claims arise out of the defendants’ alleged “acts or omissions made in” Superior Court during the litigation of the L and T matter. Pis.’ Opp’n at 9. Similar to the majority of its arguments, the defendants direct the Court to the Agreement’s forum-selection clause as support for why venue in the Eastern District of Virginia outweighs the local interest of this District to decide local controversies. Defs.’ Reply at 6. However, as the Court previously concluded, it owes the Agreement no deference because the record does not demonstrate that the plaintiffs are parties to the Agreement, see supra Part III.B, and therefore, the argument has no bearing on the Court’s analysis. On the other hand, because the dispute in this case.concerns the quality of legal representation provided in Superior Court by the defendants, who provided that representation based on membership in the District of Columbia Bar, the Court agrees that this District has a stronger local interest in this matter. Therefore, this factor weighs against transferring this case to the Eastern District of Virginia.

IV. CONCLUSION

In sum, the Court concludes that the defendants’ filing of a counterclaim in conjunction with their response to the plaintiffs’ Complaint does not bar them from moving to have this case transferred pursuant to § 1404(a), and that the plaintiffs are not parties to the forum-selection clause of the legal services Agreement which the defendants contend requires that this case be litigated in the state of Virginia. Whether this case should be transferred is therefore governed by 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a), and the Court finds that the balance of factors outlined in § 1404(a) weighs in favor of the plaintiffs’ position. Thus, this District is deemed the more appropriate forum for the adjudication of this case. Each of the private and public interest factors, with the exception of the relative congestion of both the transferee and transferor courts, weigh in favor of not transferring this case to the Eastern District of Virginia. Accordingly, the Court denies the defendants’ motion to transfer this case to the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.

8.3.4 Notes on Venue Transfer 8.3.4 Notes on Venue Transfer

Transfer Generally. There are two statutes that allow for transfer of a case to a different venue. One, Section 1404, applies when the original venue is a proper one. The other, Section 1406, applies when the original venue is not proper. Courts have also applied Section 1406 when personal jurisdiction was lacking in the original jurisdiction.

It can matter under which provision transfer is made. Under Section 1404, the law of the original jurisdiction follows the case. For example, if transfer is made under Section 1404 from a venue where the statute of limitations would allow the suit, and the case is sent to another proper venue where the statute of limitations would have blocked the suit, the more generous statute of limitations of the original forum applies. The same would be true in reverse - if a statute of limitations would bar one or more claims in the original jurisdiction, they would be barred in the district to which the case is transferred, even if that district would not have barred them had suit originally been brought there. The same applies to substantive law - if the original jurisdiction applies substantive contract or torts law differently than the receiving jurisdiction, which law applies will depend on whether transfer was made under 1404 or 1406. Under 1404, the original forum law goes with the case. Under 1406, the law of the first proper forum applies. If, for example, a case is filed in a district where the statute of limitations would not bar the suit, but venue is improper and transfer is made under 1406 to a district where venue is proper, if the statute of limitations applicable in the new district would bar the claim, that statute of limitations would apply.

Let's give some examples. Imagine that the defendants all reside in Vermont and the original lawsuit was filed in Vermont. Venue, as you will recall, is proper. But also imagine that the lawsuit arose from actions that took all place in the Southern District of California. The defendants might seek to have the case transferred to the Southern District of California. If they succeed, the law that would apply in Vermont would follow them to California.

Now imagine that there are three defendants, all residents of New York state, with two living in the Southern District of New York and one in the Eastern District of New York. Here, for some reason, the lawsuit is filed in the Western District of New York. Venue is improper (do you know why?). Imagine again that the lawsuit arose from actions that took all place in the Southern District of California and that the defendants seek to have the lawsuit transferred to the Southern District of California. If they succeed, the law that would apply if the case had first been filed in the Southern District of California will apply.

Remember: Venue After Removal is Always Proper. As you apply the different rules on applicable law under 1404 and 1406, remember that venue is proper when a case is removed from state court. Which statute would apply to a transfer made after removal?

Burden. The party seeking transfer has the burden of persuading the court that transfer is proper. When the original venue is improper, transfer normally will be preferred to dismissal.

Public and Private Interests. You saw the court addressing the public and private interests in determining whether to make transfer. The interests of the parties matter, but the court also looks at issues such as how crowded dockets are and the convenience of witnesses. As we saw earlier, a valid forum selection agreement normally will be almost but not quite absolutely controlling, but only if the parties to the lawsuit were also parties to the forum selection agreement.

Who Can Move To Transfer. You will note that the statute does not limit the right to transfer to defendants alone. Plaintiffs can also move to transfer. This might happen after a plaintiff has secured favorable law but still prefers another location, or perhaps the addition of counterclaims or additional parties might alter the plaintiff's perception of what forum should be preferred.

Time To Transfer. As this case illustrates, there is no set deadline to filing a transfer motion. Unlike removal, appeal, or even asserting a defense, there is no point at which it is simply too late under the rules. That said, the economies of transfer are more readily realized if the motion is made early in the case.

8.4 Forum Non Conveniens 8.4 Forum Non Conveniens

Forum non conveniens is a doctrine that can apply, in addition to venue, to challenge the appropriateness of a forum for the case. The remedy is dismissal, not transfer.

8.4.1 Background - Gulf Oil Corp. v. Gilbert 8.4.1 Background - Gulf Oil Corp. v. Gilbert

In Gulf Oil Corp. v. Gilbert, 330 U.S. 501 (1947), the Supreme Court addressed a situation in which the plaintiff, a resident of Virginia, sued a Pennsylvania corporation in New York court for causing an explosion and fire that consumed his warehouse in Virginia. It was uncontested that venue was proper in New York. Despite that, New York had no real connection with the lawsuit, and defendant moved for dismissal on forum non conveniens grounds. (The federal venue statutes were not enacted until a year later.)

The court held that the case was properly dismissed on forum non conveniens grounds. It reasoned:

The principle of forum non conveniens is simply that a court may resist imposition upon its jurisdiction even when jurisdiction is authorized by the letter of a general venue statute. These statutes are drawn with a necessary generality and usually give a plaintiff a choice of courts, so that he may be quite sure of some place in which to pursue his remedy. But the open door may admit those who seek not simply justice but perhaps justice blended with some harassment. A plaintiff sometimes is under temptation to resort to a strategy of forcing the trial at a most inconvenient place for an adversary, even at some inconvenience to himself.

Many of the states have met misuse of venue by investing courts with a discretion to change the place of trial on various grounds, such as the convenience of witnesses and the ends of justice. The federal law contains no such express criteria to guide the district court in exercising its power. But the problem is a very old one affecting the administration of the courts as well as the rights of litigants, and both in England and in this country the common law worked out techniques and criteria for dealing with it.

Wisely, it has not been attempted to catalogue the circumstances which will justify or require either grant or denial of remedy. The doctrine leaves much to the discretion of the court to which plaintiff resorts, and experience has not shown a judicial tendency to renounce one's own jurisdiction so strong as to result in many abuses.

If the combination and weight of factors requisite to given results are difficult to forecast or state, those to be considered are not difficult to name. An interest to be considered, and the one likely to be most pressed, is the private interest of the litigant. Important considerations are the relative ease of access to sources of proof; availability of compulsory process for attendance of unwilling, and the cost of obtaining attendance of willing, witnesses; possibility of view of premises, if view would be appropriate to the action; and all other practical problems that make trial of a case easy, expeditious and inexpensive. There may also be questions as to the enforcibility of a judgment if one is obtained. The court will weigh relative advantages and obstacles to fair trial. It is often said that the plaintiff may not, by choice of an inconvenient forum, ‘vex,’ ‘harass,’ or ‘oppress' the defendant by inflicting upon him expense or trouble not necessary to his own right to pursue his remedy. But unless the balance is strongly in favor of the defendant, the plaintiff's choice of forum should rarely be disturbed.

Factors of public interest also have place in applying the doctrine. Administrative difficulties follow for courts when litigation is piled up in congested centers instead of being handled at its origin. Jury duty is a burden that ought not to be imposed upon the people of a community which has no relation to the litigation. In cases which touch the affairs of many persons, there is reason for holding the trial in their view and reach rather than in remote parts of the country where they can learn of it by report only. There is a local interest in having localized controversies decided at home. There is an appropriateness, too, in having the trial of a diversity case in a forum that is at home with the state law that must govern the case, rather than having a court in some other forum untangle problems in conflict of laws, and in law foreign to itself.

The court revisited the doctrine in the case that follows. As you read it, take note of how the case developed, and ask yourself why the defense lawyers raised the issue when they did.

8.4.2 Piper Aircraft Co. v. Reyno 8.4.2 Piper Aircraft Co. v. Reyno

PIPER AIRCRAFT CO.

v.

REYNO, PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVE OF THE ESTATES OF FEHILLY ET AL.

Supreme Court of United States.

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

[237] James M. Fitzsimons argued the cause for petitioner in No. 80-848. With him on the brief were Charles J. McKelvey, Ann S. Pepperman, and Keith A. Jones. Warner W. Gardner argued the cause for petitioner in [238] No. 80-883. With him on the briefs were Nancy J. Bregstein and Ronald C. Scott.

Daniel C. Cathcart argued the cause and filed a brief for respondent in both cases.[2]

JUSTICE MARSHALL delivered the opinion of the Court.

These cases arise out of an air crash that took place in Scotland. Respondent, acting as representative of the estates of several Scottish citizens killed in the accident, brought wrongful-death actions against petitioners that were ultimately transferred to the United States District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania. Petitioners moved to dismiss on the ground of forum non conveniens. After noting that an alternative forum existed in Scotland, the District Court granted their motions. 479 F. Supp. 727 (1979). The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed. 630 F. 2d 149 (1980). The Court of Appeals based its decision, at least in part, on the ground that dismissal is automatically barred where the law of the alternative forum is less favorable to the plaintiff than the law of the forum chosen by the plaintiff. Because we conclude that the possibility of an unfavorable change in law should not, by itself, bar dismissal, and because we conclude that the District Court did not otherwise abuse its discretion, we reverse.

I

A

In July 1976, a small commercial aircraft crashed in the Scottish highlands during the course of a charter flight from [239] Blackpool to Perth. The pilot and five passengers were killed instantly. The decedents were all Scottish subjects and residents, as are their heirs and next of kin. There were no eyewitnesses to the accident. At the time of the crash the plane was subject to Scottish air traffic control.

The aircraft, a twin-engine Piper Aztec, was manufactured in Pennsylvania by petitioner Piper Aircraft Co. (Piper). The propellers were manufactured in Ohio by petitioner Hartzell Propeller, Inc. (Hartzell). At the time of the crash the aircraft was registered in Great Britain and was owned and maintained by Air Navigation and Trading Co., Ltd. (Air Navigation). It was operated by McDonald Aviation, Ltd. (McDonald), a Scottish air taxi service. Both Air Navigation and McDonald were organized in the United Kingdom. The wreckage of the plane is now in a hangar in Farnsborough, England.

The British Department of Trade investigated the accident shortly after it occurred. A preliminary report found that the plane crashed after developing a spin, and suggested that mechanical failure in the plane or the propeller was responsible. At Hartzell's request, this report was reviewed by a three-member Review Board, which held a 9-day adversary hearing attended by all interested parties. The Review Board found no evidence of defective equipment and indicated that pilot error may have contributed to the accident. The pilot, who had obtained his commercial pilot's license only three months earlier, was flying over high ground at an altitude considerably lower than the minimum height required by his company's operations manual.

In July 1977, a California probate court appointed respondent Gaynell Reyno administratrix of the estates of the five passengers. Reyno is not related to and does not know any of the decedents or their survivors; she was a legal secretary to the attorney who filed this lawsuit. Several days after her appointment, Reyno commenced separate wrongful-death [240] actions against Piper and Hartzell in the Superior Court of California, claiming negligence and strict liability.[3] Air Navigation, McDonald, and the estate of the pilot are not parties to this litigation. The survivors of the five passengers whose estates are represented by Reyno filed a separate action in the United Kingdom against Air Navigation, McDonald, and the pilot's estate.[4] Reyno candidly admits that the action against Piper and Hartzell was filed in the United States because its laws regarding liability, capacity to sue, and damages are more favorable to her position than are those of Scotland. Scottish law does not recognize strict liability in tort. Moreover, it permits wrongful-death actions only when brought by a decedent's relatives. The relatives may sue only for "loss of support and society."[5]

On petitioners' motion, the suit was removed to the United States District Court for the Central District of California. Piper then moved for transfer to the United States District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania, pursuant to 28 U. S. C. § 1404(a).[6] Hartzell moved to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction, or in the alternative, to transfer.[7] In December 1977, the District Court quashed service on [241] Hartzell and transferred the case to the Middle District of Pennsylvania. Respondent then properly served process on Hartzell.

B

In May 1978, after the suit had been transferred, both Hartzell and Piper moved to dismiss the action on the ground of forum non conveniens. The District Court granted these motions in October 1979. It relied on the balancing test set forth by this Court in Gulf Oil Corp. v. Gilbert, 330 U. S. 501 (1947), and its companion case, Koster v. Lumbermens Mut. Cas. Co., 330 U. S. 518 (1947). In those decisions, the Court stated that a plaintiff's choice of forum should rarely be disturbed. However, when an alternative forum has jurisdiction to hear the case, and when trial in the chosen forum would "establish . . . oppressiveness and vexation to a defendant. . . out of all proportion to plaintiff's convenience," or when the "chosen forum [is] inappropriate because of considerations affecting the court's own administrative and legal problems," the court may, in the exercise of its sound discretion, dismiss the case. Koster, supra, at 524. To guide trial court discretion, the Court provided a list of "private interest factors" affecting the convenience of the litigants, and a list of "public interest factors" affecting the convenience of the forum. Gilbert, supra, at 508-509.[8]

[242] After describing our decisions in Gilbert and Koster, the District Court analyzed the facts of these cases. It began by observing that an alternative forum existed in Scotland; Piper and Hartzell had agreed to submit to the jurisdiction of the Scottish courts and to waive any statute of limitations defense that might be available. It then stated that plaintiff's choice of forum was entitled to little weight. The court recognized that a plaintiff's choice ordinarily deserves substantial deference. It noted, however, that Reyno "is a representative of foreign citizens and residents seeking a forum in the United States because of the more liberal rules concerning products liability law," and that "the courts have been less solicitous when the plaintiff is not an American citizen or resident, and particularly when the foreign citizens seek to benefit from the more liberal tort rules provided for the protection of citizens and residents of the United States." 479 F. Supp., at 731.

The District Court next examined several factors relating to the private interests of the litigants, and determined that these factors strongly pointed towards Scotland as the appropriate forum. Although evidence concerning the design, manufacture, and testing of the plane and propeller is located in the United States, the connections with Scotland are otherwise "overwhelming." Id., at 732. The real parties in interest are citizens of Scotland, as were all the decedents. Witnesses who could testify regarding the maintenance of the aircraft, the training of the pilot, and the investigation of the accident — all essential to the defense — are in Great Britain. Moreover, all witnesses to damages are located in Scotland. Trial would be aided by familiarity with Scottish topography, and by easy access to the wreckage.

The District Court reasoned that because crucial witnesses and evidence were beyond the reach of compulsory process, and because the defendants would not be able to implead potential Scottish third-party defendants, it would be "unfair to make Piper and Hartzell proceed to trial in this forum." Id., [243] at 733. The survivors had brought separate actions in Scotland against the pilot, McDonald, and Air Navigation. "[I]t would be fairer to all parties and less costly if the entire case was presented to one jury with available testimony from all relevant witnesses." Ibid. Although the court recognized that if trial were held in the United States, Piper and Hartzell could file indemnity or contribution actions against the Scottish defendants, it believed that there was a significant risk of inconsistent verdicts.[9]

The District Court concluded that the relevant public interests also pointed strongly towards dismissal. The court determined that Pennsylvania law would apply to Piper and Scottish law to Hartzell if the case were tried in the Middle District of Pennsylvania.[10] As a result, "trial in this forum would be hopelessly complex and confusing for a jury." Id., at 734. In addition, the court noted that it was unfamiliar with Scottish law and thus would have to rely upon experts from that country. The court also found that the trial would be enormously costly and time-consuming; that it would be unfair to burden citizens with jury duty when the Middle District [244] of Pennsylvania has little connection with the controversy; and that Scotland has a substantial interest in the outcome of the litigation.

In opposing the motions to dismiss, respondent contended that dismissal would be unfair because Scottish law was less favorable. The District Court explicitly rejected this claim. It reasoned that the possibility that dismissal might lead to an unfavorable change in the law did not deserve significant weight; any deficiency in the foreign law was a "matter to be dealt with in the foreign forum." Id., at 738.

C

On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed and remanded for trial. The decision to reverse appears to be based on two alternative grounds. First, the Court held that the District Court abused its discretion in conducting the Gilbert analysis. Second, the Court held that dismissal is never appropriate where the law of the alternative forum is less favorable to the plaintiff.

The Court of Appeals began its review of the District Court's Gilbert analysis by noting that the plaintiff's choice of forum deserved substantial weight, even though the real parties in interest are nonresidents. It then rejected the District Court's balancing of the private interests. It found that Piper and Hartzell had failed adequately to support their claim that key witnesses would be unavailable if trial were held in the United States: they had never specified the witnesses they would call and the testimony these witnesses would provide. The Court of Appeals gave little weight to the fact that piper and Hartzell would not be able to implead potential Scottish third-party defendants, reasoning that this difficulty would be "burdensome" but not "unfair," 630 F. 2d, at 162.[11] Finally, the court stated that resolution of the suit [245] would not be significantly aided by familiarity with Scottish topography, or by viewing the wreckage.

The Court of Appeals also rejected the District Court's analysis of the public interest factors. It found that the District Court gave undue emphasis to the application of Scottish law: " `the mere fact that the court is called upon to determine and apply foreign law does not present a legal problem of the sort which would justify the dismissal of a case otherwise properly before the court.' " Id., at 163 (quoting Hoffman v. Goberman, 420 F. 2d 423, 427 (CA3 1970)). In any event, it believed that Scottish law need not be applied. After conducting its own choice-of-law analysis, the Court of Appeals determined that American law would govern the actions against both Piper and Hartzell.[12] The same choice-of-law analysis apparently led it to conclude that Pennsylvania and Ohio, rather than Scotland, are the jurisdictions with the greatest policy interests in the dispute, and that all other public interest factors favored trial in the United States.[13]

[246] In any event, it appears that the Court of Appeals would have reversed even if the District Court had properly balanced the public and private interests. The court stated:

"[I]t is apparent that the dismissal would work a change in the applicable law so that the plaintiff's strict liability claim would be eliminated from the case. But . . . a dismissal for forum non conveniens, like a statutory transfer, `should not, despite its convenience, result in a change in the applicable law.' Only when American law is not applicable, or when the foreign jurisdiction would, as a matter of its won choice of law, give the plaintiff the benefit of the claim to which she is entitled here, would dismissal be justified." 630 F. 2d, at 163-164 (footnote omitted) (quoting DeMateos v. Texaco, Inc., 562 F. 2d 895, 899 (CA3 1977), cert. denied, 435 U. S. 904 (1978)).

In other words, the court decided that dismissal is automatically barred if it would lead to a change in the applicable law unfavorable to the plaintiff.

We granted certiorari in these case to consider the questions they raise concerning the proper application of the doctrine of forum non conveniens. 450 U. S. 909 (1981).[14]

[247] II

The Court of Appeals erred in holding that plaintiffs may defeat a motion to dismiss on the ground of forum non conveniens merely by showing that the substantive law that would be applied in the alternative forum is less favorable to the plaintiffs than that of the present forum. The possibility of a change in substantive law should ordinarily not be given conclusive or even substantial weight in the forum non conveniens inquiry.

We expressly rejected the position adopted by the Court of Appeals in our decision in Canada Malting Co. v. Paterson Steamships, Ltd., 285 U. S. 413 (1932). That case arose out of a collision between two vessels in American waters. The Canadian owners of cargo lost in the accident sued the Canadian owners of one of the vessels in Federal District Court. The cargo owners chose an American court in large part because the relevant American liability rules were more favorable than the Canadian rules. The District Court dismissed on grounds of forum non conveniens. The plaintiffs argued that dismissal was inappropriate because Canadian laws were less favorable to them. This Court nonetheless affirmed:

"We have no occasion to enquire by what law rights of the parties are governed, as we are of the opinion [248] that, under any view of that question, it lay within the discretion of the District Court to decline to assume jurisdiction over the controversy. . . . `[T]he court will not take cognizance of the case if justice would be as well done by remitting the parties to their home forum.' " Id., at 419-420 (quoting Charter Shipping Co. v. Bowring, Jones & Tidy, Ltd., 281 U. S. 515, 517 (1930).

The Court further stated that "[t]here was no basis for the contention that the District Court abused its discretion." 285 U. S., at 423.

It is true that Canada Malting was decided before Gilbert, and that the doctrine of forum non conveniens was not fully crystallized until our decision in that case.[15] However, Gilbert in no way affects the validity of Canada Malting. Indeed, [249] by holding that the central focus of the forum non conveniens inquiry is convenience, Gilbert implicitly recognized that dismissal may not be barred solely because of the possibility of an unfavorable change in law.[16] Under Gilbert, dismissal will ordinarily be appropriate where trial in the plaintiff's chosen forum imposes a heavy burden on the defendant or the court, and where the plaintiff is unable to offer any specific reasons of convenience supporting his choice.[17] If substantial weight were given to the possibility of an unfavorable change in law, however, dismissal might be barred even where trial in the chosen forum was plainly inconvenient.

The Court of Appeals' decision is inconsistent with this Court's earlier forum non conveniens decisions in another respect. Those decisions have repeatedly emphasized the need to retain flexibility. In Gilbert, the Court refused to identify specific circumstances "which will justify or require either grant or denial of remedy." 330 U. S., at 508. Similarly, in Koster, the Court rejected the contention that where a trial would involve inquiry into the internal affairs of a foreign corporation, dismissal was always appropriate. "That is one, but only one, factor which may show convenience." 330 U. S., at 527. And in Williams v. Green Bay & Western R. Co., 326 U. S. 549, 557 (1946), we stated that we would not lay down a rigid rule to govern discretion, and that "[e]ach case turns on its facts." If central emphasis were [250] placed on any one factor, the forum non conveniens doctrine would lose much of the very flexibility that makes it so valuable.

In fact, if conclusive or substantial weight were given to the possibility of a change in law, the forum non conveniens doctrine would become virtually useless. Jurisdiction and venue requirements are often easily satisfied. As a result, many plaintiffs are able to choose from among several forums. Ordinarily, these plaintiffs will select that forum whose choice-of-law rules are most advantageous. Thus, if the possibility of an unfavorable change in substantive law is given substantial weight in the forum non conveniens inquiry, dismissal would rarely be proper.

Except for the court below, every Federal Court of Appeals that has considered this question after Gilbert has held that dismissal on grounds of forum non conveniens may be granted even though the law applicable in the alternative forum is less favorable to the plaintiff's chance of recovery. See, e. g., Pain v. United Technologies Corp., 205 U. S. App. D. C. 229, 248-249, 637 F. 2d 775, 794-795 (1980); Fitzgerald v. Texaco, Inc., 521 F. 2d 448, 453 (CA2 1975), cert. denied, 423 U. S. 1052 (1976); Anastasiadis v. S.S. Little John, 346 F. 2d 281, 283 (CA5 1965), cert. denied, 384 U. S. 920 (1966).[18] Several Courts have relied expressly on Canada Malting to hold that the possibility of an unfavorable change of law should not, by itself, bar dismissal. See Fitzgerald [251] v. Texaco, Inc., supra; Anglo-American Grain Co. v. The S/T Mina D'Amico, 169 F. Supp. 908 (ED Va. 1959).

The Court of Appeals' approach is not only inconsistent with the purpose of the forum non conveniens doctrine, but also poses substantial practical problems. If the possibility of a change in law were given substantial weight, deciding motions to dismiss on the ground of forum non conveniens would become quite difficult. Choice-of-law analysis would become extremely important, and the courts would frequently be required to interpret the law of foreign jurisdictions. First, the trial court would have to determine what law would apply if the case were tried in the chosen forum, and what law would apply if the case were tried in the alternative forum. It would then have to compare the rights, remedies, and procedures available under the law that would be applied in each forum. Dismissal would be appropriate only if the court concluded that the law applied by the alternative forum is as favorable to the plaintiff as that of the chosen forum. The doctrine of forum non conveniens, however, is designed in part to help courts avoid conducting complex exercises in comparative law. As we stated in Gilbert, the public interest factors point towards dismissal where the court would be required to "untangle problems in conflict of laws, and in law foreign to itself." 330 U. S., at 509.

Upholding the decision of the Court of Appeals would result in other practical problems. At least where the foreign plaintiff named an American manufacturer as defendant,[19] a court could not dismiss the case on grounds of forum non [252] conveniens where dismissal might lead to an unfavorable change in law. The American courts, which are already extremely attractive to foreign plaintiffs,[20] would become even more attractive. The flow of litigation into the United States would increase and further congest already crowded courts.[21]

[253] The Court of Appeals based its decision, at least in part, on an analogy between dismissals on grounds of forum non conveniens and transfers between federal courts pursuant to § 1404(a). In Van Dusen v. Barrack, 376 U. S. 612 (1964), this Court ruled that a § 1404(a) transfer should not result in a change in the applicable law. Relying on dictum in an earlier Third Circuit opinion interpreting Van Dusen, the court below held that that principle is also applicable to a dismissal on forum non conveniens grounds. 630 F. 2d, at 164, and n. 51 (citing DeMateos v. Texaco, Inc., 562 F. 2d, at 899). However, § 1404(a) transfers are different than dismissals on the ground of forum non conveniens.

Congress enacted § 1404(a) to permit change of venue between federal courts. Although the statute was drafted in accordance with the doctrine of forum non conveniens, see Revisor's Note, H. R. Rep. No. 308, 80th Cong., 1st Sess., A132 (1947); H. R. Rep. No. 2646, 79th Cong., 2d Sess., A127 (1946), it was intended to be a revision rather than a codification of the common law. Norwood v. Kirkpatrick, 349 U. S. 29 (1955). District courts were given more discretion to transfer under § 1404(a) than they had to dismiss on grounds of forum non conveniens. Id., at 31-32.