10 Pleading 10 Pleading

Pleading presents a basic choice for designers of civil procedure systems. As with other such fundamental choices, there are follow-on consequences with regard to the entire system. Keep that in mind as you sort out how US pleading works.

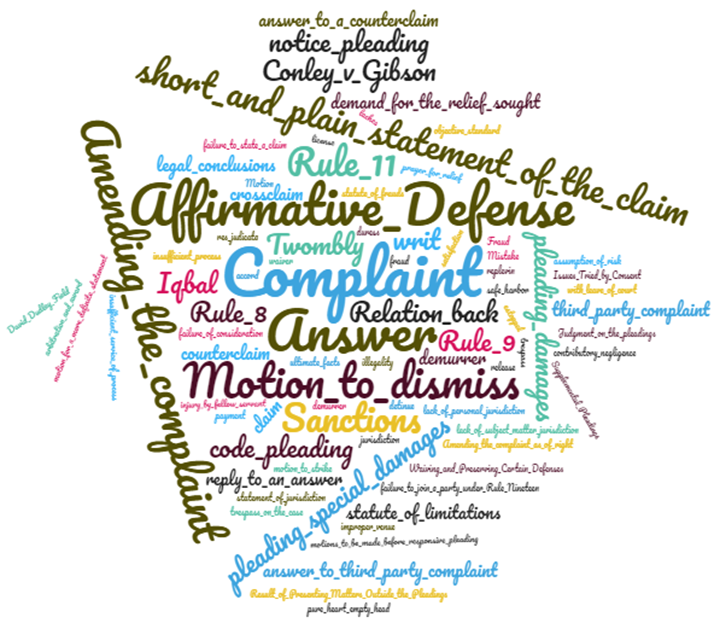

10.1 Pleading Wordcloud 10.1 Pleading Wordcloud

10.2 Pleading Generally - The Complaint 10.2 Pleading Generally - The Complaint

10.2.1 Introduction to Pleading 10.2.1 Introduction to Pleading

In this section of the course we look at pleading – the process through which claims and responses are set out in writing.

The federal rules are a system, and as in any system choices made with one part will affect other parts. That is true with respect to pleading. Pleading serves many purposes, and the designers of a procedural system have decide which aspects of pleading are given preference. This, in turn, will affect how other aspects of the procedural system function.

Some of the things pleading might try to achieve include:

• Start the litigation

• Provide Notice

• Set out the facts underlying claims and defenses

• Identify causes of action and defenses

• Screen or filter out bad cases (e.g., cases that invoke no accepted legal theory)

• Simplify case for resolution

• Help to define what case was about for purposes of using the judgment to preclude or assist future claims

In looking at balancing between the functions of pleading, choices arise. These include:

• Should pleading be used to resolve the case, or just to set the stage?

• How much factual detail should be required - or permitted?

• Once a party has set out its position in pleadings, should it be allowed to amend its pleadings and so change the positions it has taken?

• Do we apply the same pleading rules to all kinds of cases?

• Should we allow a party to assert multiple - and perhaps even inconsistent - legal and factual theories in pleadings and responses?

• Once a pleading has been entered, do statutes of limitations affect changes to that pleading?

Think back to our case involving the student disappearance of a remarkable pig from a farmer's pig pen. As you read through the following short history of pleading, think about how different pleading systems would approach a lawsuit based on that disappearance. Think also about how the roles assigned to the pleading stage have an effect on what need not or must be handled at other stages of the case.

10.2.2 The History and Purposes of American Pleading 10.2.2 The History and Purposes of American Pleading

This section has been excerpted from Ray Worthy Campbell, Getting a Clue: Two Stage Complaint Pleading as a Solution to the Conley-Iqbal Dilemma, 114 Penn St. L. Rev. 1191 (2010). Most citations have been omitted but are available in the original.

The History and Purposes of Pleadings

Much has been asked of pleadings. At times, such as under the common law, the pleading process served to define and narrow the case. Under Code pleading, the pleadings set forth the essential facts and defined the contours of the case. The complaint was required to set forth the facts supporting the cause of action, with those same facts acting as boundaries beyond which no proof could be introduced. Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which shifted more of the burden of defining and shaping litigation to discovery, pleadings were asked first and foremost to provide notice.

As Charles Clark summarized the shifting function of pleadings more than a decade before the adoption of the Federal Rules:

[T]he purpose especially emphasized has varied from time to time. Thus in common law pleading especial emphasis was placed upon the issue-formulating function of pleading; under the earlier code pleading like emphasis was placed upon stating the material, ultimate facts in the pleadings: while at the present time the emphasis seems to have shifted to the notice function of pleading.

Even under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the humble complaint must play multiple roles. Its filing supplies a start date for the litigation process. It provides notice of the nature of the claims being asserted. It identifies at least some of the relevant facts and sets the boundaries within which further facts may be developed during discovery. In conjunction with the answer and any later amended complaints, it defines and narrows the issues that must be resolved at trial. It provides a means for testing, and when appropriate dismissing, claims without a legal basis or for which jurisdiction does not lie. When litigation has ended, the complaint helps identify, for purposes of issue and claim preclusion, which issues were and might have been litigated.

A pleading standard that works brilliantly for one of these tasks – say, narrowing the issues for trial – might prove cumbersome for another, such as notice. In thinking about pleadings, it must be asked whether (and how much) pleadings should be used to resolve the litigation, and how much it should be used just to set the stage for other modes of resolution.

A. The Common Law and Code Eras: Narrowing and Defining the Case

At one time, pleadings played a much more central role in developing litigation than they do today. In both the common law and code eras pleadings were used to narrow and define the case. Under equity, pleadings took on the additional role of providing evidence to the court, substituting in large part for the trial. While these pleading regimes carried a cost – particularly in creating technical traps for the unwary and sometimes expanding the cost of the overall litigation – they did have the advantage of sometimes properly eliminating meritless cases and of simplifying and narrowing trial.

1. Common Law Pleading

In the Common Law era, pleading practice focused on narrowing and defining the case. It did not rely on the opening document to achieve that function, but achieved case definition through an extensive exchange of pleadings. The initial writ provided notice, some statement of the facts underlying the claim, and indication of the legal theory. Then commenced a complex dance of response and counter-response. The defendant denied or admitted the facts alleged, challenged the legal sufficiency of the allegations through demurrers, or presented defenses that would defeat the claim even given the truth of plaintiff’s allegations. The exchange of pleadings could proceed through several iterations, with each new round providing traps for the unwary.

Common law pleading practice possessed one cardinal virtue – it simplified trial. The goal of the complex exchange of pleadings was to narrow the case to a single issue of fact or law that could be decided at trial. Compared to modern trials, the common law trial was a straightforward affair. Disputes could be tried in days, if not hours, and typically presented non-technical issues that a jury of common folk could readily comprehend.

The path to the trial, however, imposed substantial costs. Much depended on technicalities. Perhaps the most fundamental of these, until abolished, were the ancient forms of action. In part procedural, in part substantive, the forms provided for a certain kind of remedy for a certain kind of harm.

Let it be granted that one man has been wronged by another; the first thing that he or his advisers have to consider is what form of action he shall bring. It is not enough that in some way or another he should compel his adversary to appear in court and should then state in the words that naturally occur to him the facts on which he relies and the remedy to which he thinks himself entitled. No, English law knows a certain number of forms of action, each with its own uncouth name, a writ of right, an assize of novel disseisin or of mort d'ancestor, a writ of entry sur disseisin in the per and cui, a writ of besaiel, of quare impedit, an action of covenant, debt, detinue, replevin, trespass, assumpsit, ejectment, case. This choice is not merely a choice between a number of queer technical terms, it is a choice between methods of procedure adapted to cases of different kinds.

F. W. Maitland, The Forms of Action at Common Law 1, (A.H. Chaytor and W.J. Whittaker ed.) (1909)

At the outset of the lawsuit, the plaintiff faced irrevocable and consequential choices. Each form of action carried with it procedural anomalies – such as how jurisdiction over the defendant might be obtained, and which remedies would be available. Each also corresponded to certain kinds of facts, but not, however closely related, to others. Choosing a not-quite-right form of action meant dismissal. “The plaintiff must sue either in case or in trespass, and upon the accuracy of his claim depended the success of his action.”

Choosing the right form of action was only the first of many pleading choices fraught with danger. For example, a defendant could not deny the legal basis for the claim while challenging the facts; a choice had to made between a demurrer and a denial. Once a choice was made, there was no going back for a do-over.

As time went on, the defects of common law pleading became increasingly clear. The pleading phase of the case could take a long time and cost a lot of money, pushing off the resolution of the case on the merits and pricing some litigants out of court. Worse than that, the pitfalls of pleading meant that some cases could be resolved on grounds that had nothing to do with the merits.

2. Equity Pleading

Pleading in equity followed its own distinct course, but also served to narrow and define the case. A suit in equity was commenced by filing a bill of complaint. The bill of complaint set forth the facts of the case along with a prayer for relief. The bill of equity included interrogatories to the opposing party, and as pleadings were exchanged much of the proof in the case was submitted through the pleadings themselves.

Fact pleading also was the rule in equity. The bill, which was used to initiate proceedings in Chancery, required as an essential element a listing of the facts which the plaintiff expected to prove, to which the defendant was required to respond with either admissions or denials under oath. While much of practice under the modern rules – such as joinder of parties and claims – derives from equity practice, modern notice pleading does not.

3. Code Pleading

With the industrial revolution well under way, the arcane and treacherous intricacies of common law pleading must have seemed as out of date as a torch lit medieval workshop. In an era that broke new ground in industrial efficiency and productivity, it was only natural that reformers wished the same for legal processes. The sometimes absurd technicalities of the common law looked ripe for replacement by a rationally engineered replacement.

The most influential of the U.S. reform efforts, the Field Code, sought to remedy the flaws of common law pleading by substituting “fact” pleading that diminished the importance of the causes of action. The complaint in code pleading dispensed with naming the cause of action in favor of a document setting forth the facts of the case. The goal was in part to simplify the process, and in part to reduce the ability of judges to act capriciously.

This new approach soon revealed problems of its own. Two merit mentioning. First, distinctions between “facts” and “ultimate facts” proved not so simple in application. Second, in order to avoid surprise and discipline the pleading process, the proof offered at trial could not go beyond the allegations of the complaint. The disputes over what constituted proper pleading of facts enabled expensive wrangling over the pleadings, while the limitation on proof beyond the pleadings, coupled with restrictions on amending the complaint, sometimes made difficult adapting the case to factual developments..

B. 20th Century American Innovation: Notice Pleading

By the early 20th century it had become clear that neither code pleading nor common law pleading was the ideal solution to launching a lawsuit. Perhaps because lawyers of the era were so thoroughly steeped in common law traditions, technicalities proved resilient in legal practice. A new reform movement arose, this time directed at resolving cases on the merits rather than on technicalities. To achieve this, it seemed clear to some that the role of pleadings should be diminished.

An early advocate for reform was Roscoe Pound, then dean of the law school at the University of Nebraska. In a famous 1906 address to the American Bar Association, he decried what he saw as the “sporting theory of justice” where lawyerly skill mattered more than the merits and pushed for a new approach. For Pound, "the sole office of pleadings should be to give notice to the respective parties of the claims, defenses and cross-demands asserted by their adversaries."

Notice pleading quickly attracted adherents. In the 30 years following Pound’s speech, a theory of notice pleading developed. This theory would diminish the role pleading might play in narrowing and resolving the case; at the same time, litigants would no longer need to fear pleading as a trap. So long as the function of notice was served, the litigation could proceed to resolution on the merits, with the expectation that merits resolution would yield more accurate and more respected results.

C. Pleading Under The Federal Rules

In the latter part of the 1930s, a confluence of events enabled a dramatic change in American federal court procedure. The passage of the Rules Enabling Act created two possibilities: merging equity and common law in the federal courts and the codification of federal procedure. This moved notice pleading from an academic concept to reality.

Charles Clark, a pleading expert and the principal draftsman of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, was a believer in simplified notice pleading. Largely as a result of Clark’s influence, notice pleading was incorporated in the new Federal Rules of Civil Procedure adopted in 1938. Under this approach, the plaintiff was required only to provide “a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief.” Pleading formalities, whether of facts or causes of action, were out; getting to the facts through discovery and resolving the claims on the merits was in.

The adoption of such minimal notice pleading was an American innovation. No modern pleading regime had required so little. Even today, pleading systems worldwide typically require fact pleading – often at a level far beyond what Americans think of as fact pleading.

1. Liberal Pleading In The Context Of Other FRCP Innovations

Notice pleading was far from the only innovation in the new federal rules. For our purposes, two stand out – liberal joinder and expansive discovery. Along with notice pleading, these innovations changed the nature of what constituted a lawsuit.

Liberal joinder of claims and parties, an approach modeled on equity procedure, expanded the scope of lawsuits. Under the common law, a writ by its nature stated a single cause of action. A case arose from and was linked conceptually to the specific legal right asserted. Under fact pleading, the facts laid out in the complaint circumscribed the litigation, and the plaintiff could not easily develop a case different from the alleged facts.

That changed under the federal rules. Under the federal rules, the contours of a case or controversy are no longer linked to the legal right asserted. Rather, the federal rules model looks to the “transaction or occurrence” from which the dispute arose. Multiple and inconsistent causes of action can be asserted based on the common transaction or occurrence; claims and counterclaims that are part of the transaction and occurrence complained of will be barred in future litigation the same as if they had been tried and lost. The goal was efficient and equitable handling of the underlying dispute without undue regard to technicalities.

This change allowed multiple defendants to be joined in a single action, so that complete justice could be done in one trial. It also allowed the assertion of multiple legal theories, so that plaintiffs need not fear losing a meritorious case because the wrong legal theory was asserted. This inclusive approach drew upon equitable tradition, and deferred until later in the case the task of narrowing the parties and issues involved.

The new rules also allowed an unprecedented amount of pretrial discovery. While pretrial discovery was known, to a limited degree, in code pleading and to a greater degree in equity practice, the new rules provided for a range of discovery tools that exceeded in scope anything that had previously existed in any one system.

That the federal rules marked a bold new step in legal procedure was clear at the time. What was perhaps less clear was exactly how the process of litigation would change as lawyers became familiar with the new tools provided. As this article will show, the combination of liberal joinder, expansive discovery and scant pleading opened the way to a new kind of litigation centered less on either pleadings or trial than had been the case in the past.

2. Conley: Notice Pleading Confirmed

While the Federal Rules clearly marked a change in direction, the rules left room for interpretation. In particular, the exact nature of what constituted adequate pleading was inherently a bit hazy under Rule 8, given the rule’s careful avoidance of either of the words “fact” or “notice.” While Clark clearly favored a liberal notice pleading regime requiring little in the way of fact pleading, other scholars, as well as some judges and attorneys, preferred a more restrictive pleading regime. For nearly 20 years after the adoption of the rules, uncertainty remained about just how much factual detail was required under Rule 8’s “sort and plain statement” of the case.

The haziness was cleared in the landmark case of Conley v. Gibson.

10.2.3 First National Bank v. St. Croix Boom Corp. 10.2.3 First National Bank v. St. Croix Boom Corp.

This short case is included to give you a taste of the complexity and the pitfalls of pleading under both the common law and fact pleading. Here, in a code pleading regime, plaintiff could have gotten by with a general allegation, but alleged some facts. See what happens and ask yourself if that makes sense. From a systems design standpoint, ask yourself if the kind of discussion required in this case is a good use of scarce judicial resources.

First National Bank of Anoka vs. St. Croix Boom Corporation.

June 27, 1889.

Pleading — General Averment of Title Controlled by Facts Pleaded. Where a pleading sets out the facts by which the party claims to have acquired title to property, followed by a general allegation of ownership as a result of such facts, the particular facts alleged will control; and, if they are insufficient to sustain such result, the pleading is bad. Following Pinney v. Fridley, 9 Minn. 23, (34.)

Same — Conversion, how' Alleged. — In an action for wrongful conversion it is not necessary to plead the specific acts constituting the alleged conversion. A general allegation that the defendant has wrongfully eon- ' verted the property is sufficient.

Appeal by defendant from an order of the municipal court of Still-water, overruling its demurrer to the complaint in an action for the. conversion of 17,000 feet of logs of the value of $ 136.

J. N. & I. W. Castle, for appellant.

C. P. Gregory, for respondent.

The only allegation in the complaint as to plaintiff’s right to or interest in the property alleged to have been wrongfully converted is “that the plaintiff, in the regular course of business, and to effect the payment of money already loaned and a debt owing, took an assignment of the logs marked F. D. A., and of the logs .bearing said mark, on or about the 9th of February, 1884, and then and thereby became, and ever since has continued to be, the owner of all the logs bearing said mark.” The pleader might have contented himself with a general allegation of ownership, but he has attempted to set out all the facts by which the plaintiff became the owner, and *142then the general result following from those facts. In such a form of pleading the particular facts alleged will control, and, if they do not sustain the result reached, the pleading is bad. Pinney v. Fridley, 9 Minn. 23, (34.) In this case there are no facts alleged to support the conclusion that the plaintiff became the owner of the logs. It is not alleged by whom or to whom the money was loaned or the debt was owing, or from whom the assignment was taken, or that the party from whom taken had any interest in the logs. In fact it would appear that the pleader had studiously avoided alleging any material fact. The complaint, therefore, did not state a cause of action.

The second objection to the complaint, viz., that it does not state the particular acts constituting the alleged conversion, is not well taken. This is not necessary. A general allegation that the defendant has wrongfully converted the property is sufficient; but on the first ground the demurrer should have been sustained.

Order reversed.

10.2.4 Rule 7. Pleadings Allowed; Form of Motions and Other Papers 10.2.4 Rule 7. Pleadings Allowed; Form of Motions and Other Papers

(a) Pleadings. Only these pleadings are allowed:

(1) a complaint;

(2) an answer to a complaint;

(3) an answer to a counterclaim designated as a counterclaim;

(4) an answer to a crossclaim;

(5) a third-party complaint;

(6) an answer to a third-party complaint; and

(7) if the court orders one, a reply to an answer.

(b) Motions and Other Papers.

(1) In General. A request for a court order must be made by motion. The motion must:

(A) be in writing unless made during a hearing or trial;

(B) state with particularity the grounds for seeking the order; and

(C) state the relief sought.

(2) Form. The rules governing captions and other matters of form in pleadings apply to motions and other papers.

10.2.5 Rule 8. General Rules of Pleading 10.2.5 Rule 8. General Rules of Pleading

(a) Claim for Relief. A pleading that states a claim for relief must contain:

(1) a short and plain statement of the grounds for the court's jurisdiction, unless the court already has jurisdiction and the claim needs no new jurisdictional support;

(2) a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief; and

(3) a demand for the relief sought, which may include relief in the alternative or different types of relief.

(b) Defenses; Admissions and Denials.

(1) In General. In responding to a pleading, a party must:

(A) state in short and plain terms its defenses to each claim asserted against it; and

(B) admit or deny the allegations asserted against it by an opposing party.

(2) Denials—Responding to the Substance. A denial must fairly respond to the substance of the allegation.

(3) General and Specific Denials. A party that intends in good faith to deny all the allegations of a pleading—including the jurisdictional grounds—may do so by a general denial. A party that does not intend to deny all the allegations must either specifically deny designated allegations or generally deny all except those specifically admitted.

(4) Denying Part of an Allegation. A party that intends in good faith to deny only part of an allegation must admit the part that is true and deny the rest.

(5) Lacking Knowledge or Information. A party that lacks knowledge or information sufficient to form a belief about the truth of an allegation must so state, and the statement has the effect of a denial.

(6) Effect of Failing to Deny. An allegation—other than one relating to the amount of damages—is admitted if a responsive pleading is required and the allegation is not denied. If a responsive pleading is not required, an allegation is considered denied or avoided.

(c) Affirmative Defenses.

(1) In General. In responding to a pleading, a party must affirmatively state any avoidance or affirmative defense, including:

• accord and satisfaction;

• arbitration and award;

• assumption of risk;

• contributory negligence;

• duress;

• estoppel;

• failure of consideration;

• fraud;

• illegality;

• injury by fellow servant;

• laches;

• license;

• payment;

• release;

• res judicata;

• statute of frauds;

• statute of limitations; and

• waiver.

(2) Mistaken Designation. If a party mistakenly designates a defense as a counterclaim, or a counterclaim as a defense, the court must, if justice requires, treat the pleading as though it were correctly designated, and may impose terms for doing so.

(d) Pleading to Be Concise and Direct; Alternative Statements; Inconsistency.

(1) In General. Each allegation must be simple, concise, and direct. No technical form is required.

(2) Alternative Statements of a Claim or Defense. A party may set out 2 or more statements of a claim or defense alternatively or hypothetically, either in a single count or defense or in separate ones. If a party makes alternative statements, the pleading is sufficient if any one of them is sufficient.

(3) Inconsistent Claims or Defenses. A party may state as many separate claims or defenses as it has, regardless of consistency.

(e) Construing Pleadings. Pleadings must be construed so as to do justice.

10.2.6 Conley v. Gibson 10.2.6 Conley v. Gibson

CONLEY ET AL.

v.

GIBSON ET AL.

Supreme Court of United States.

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT.

[42] Joseph C. Waddy argued the cause for petitioners. With him on the brief were Roberson L. King, Robert L. Carter, William C. Gardner and William B. Bryant.

Edward J. Hickey, Jr. argued the cause for respondents. With him on the brief was Clarence M. Mulholland.

MR. JUSTICE BLACK delivered the opinion of the Court.

Once again Negro employees are here under the Railway Labor Act[1] asking that their collective bargaining agent be compelled to represent them fairly. In a series of cases beginning with Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co., 323 U. S. 192, this Court has emphatically and repeatedly ruled that an exclusive bargaining agent under the Railway Labor Act is obligated to represent all employees in the bargaining unit fairly and without discrimination because of race and has held that the courts have power to protect employees against such invidious discrimination.[2]

This class suit was brought in a Federal District Court in Texas by certain Negro members of the Brotherhood of Railway and Steamship Clerks, petitioners here, on behalf of themselves and other Negro employees similarly situated against the Brotherhood, its Local Union No. 28 and certain officers of both. In summary, the complaint [43] made the following allegations relevant to our decision: Petitioners were employees of the Texas and New Orleans Railroad at its Houston Freight House. Local 28 of the Brotherhood was the designated bargaining agent under the Railway Labor Act for the bargaining unit to which petitioners belonged. A contract existed between the Union and the Railroad which gave the employees in the bargaining unit certain protection from discharge and loss of seniority. In May 1954, the Railroad purported to abolish 45 jobs held by petitioners or other Negroes all of whom were either discharged or demoted. In truth the 45 jobs were not abolished at all but instead filled by whites as the Negroes were ousted, except for a few instances where Negroes were rehired to fill their old jobs but with loss of seniority. Despite repeated pleas by petitioners, the Union, acting according to plan, did nothing to protect them against these discriminatory discharges and refused to give them protection comparable to that given white employees. The complaint then went on to allege that the Union had failed in general to represent Negro employees equally and in good faith. It charged that such discrimination constituted a violation of petitioners' right under the Railway Labor Act to fair representation from their bargaining agent. And it concluded by asking for relief in the nature of declaratory judgment, injunction and damages.

The respondents appeared and moved to dismiss the complaint on several grounds: (1) the National Railroad Adjustment Board had exclusive jurisdiction over the controversy; (2) the Texas and New Orleans Railroad, which had not been joined, was an indispensable party defendant; and (3) the complaint failed to state a claim upon which relief could be given. The District Court granted the motion to dismiss holding that Congress had given the Adjustment Board exclusive jurisdiction over [44] the controversy. The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, apparently relying on the same ground, affirmed. 229 F. 2d 436. Since the case raised an important question concerning the protection of employee rights under the Railway Labor Act we granted certiorari. 352 U. S. 818.

We hold that it was error for the courts below to dismiss the complaint for lack of jurisdiction. They took the position that § 3 First (i) of the Railway Labor Act conferred exclusive jurisdiction on the Adjustment Board because the case, in their view, involved the interpretation and application of the collective bargaining agreement. But § 3 First (i) by its own terms applies only to "disputes between an employee or group of employees and a carrier or carriers."[3] This case involves no dispute between employee and employer but to the contrary is a suit by employees against the bargaining agent to enforce their statutory right not to be unfairly discriminated against by it in bargaining.[4] The Adjustment Board has no [45] power under § 3 First (i) or any other provision of the Act to protect them from such discrimination. Furthermore, the contract between the Brotherhood and the Railroad will be, at most, only incidentally involved in resolving this controversy between petitioners and their bargaining agent.

Although the District Court did not pass on the other reasons advanced for dismissal of the complaint we think it timely and proper for us to consider them here. They have been briefed and argued by both parties and the respondents urge that the decision below be upheld, if necessary, on these other grounds.

As in the courts below, respondents contend that the Texas and New Orleans Railroad Company is an indispensable party which the petitioners have failed to join as a defendant. On the basis of the allegations made in the complaint and the relief demanded by petitioners we believe that contention is unjustifiable. We cannot see how the Railroad's rights or interests will be affected by this action to enforce the duty of the bargaining representative to represent petitioners fairly. This is not a suit, directly or indirectly, against the Railroad. No relief is asked from it and there is no prospect that any will or can be granted which will bind it. If an issue does develop which necessitates joining the Railroad either it or the respondents will then have an adequate opportunity to request joinder.

Turning to respondents' final ground, we hold that under the general principles laid down in the Steele, Graham, and Howard cases the complaint adequately set forth a claim upon which relief could be granted. In appraising the sufficiency of the complaint we follow, of course, the accepted rule that a complaint should not be dismissed for failure to state a claim unless it appears beyond doubt that the plaintiff can prove no set of facts [46] in support of his claim which would entitle him to relief.[5] Here, the complaint alleged, in part, that petitioners were discharged wrongfully by the Railroad and that the Union, acting according to plan, refused to protect their jobs as it did those of white employees or to help them with their grievances all because they were Negroes. If these allegations are proven there has been a manifest breach of the Union's statutory duty to represent fairly and without hostile discrimination all of the employees in the bargaining unit. This Court squarely held in Steele and subsequent cases that discrimination in representation because of race is prohibited by the Railway Labor Act. The bargaining representative's duty not to draw "irrelevant and invidious"[6] distinctions among those it represents does not come to an abrupt end, as the respondents seem to contend, with the making of an agreement between union and employer. Collective bargaining is a continuing process. Among other things, it involves day-to-day adjustments in the contract and other working rules, resolution of new problems not covered by existing agreements, and the protection of employee rights already secured by contract. The bargaining representative can no more unfairly discriminate in carrying out these functions than it can in negotiating a collective agreement.[7] A contract may be fair and impartial on its face yet administered in such a way, with the active or tacit consent of the union, as to be flagrantly discriminatory against some members of the bargaining unit.

[47] The respondents point to the fact that under the Railway Labor Act aggrieved employees can file their own grievances with the Adjustment Board or sue the employer for breach of contract. Granting this, it still furnishes no sanction for the Union's alleged discrimination in refusing to represent petitioners. The Railway Labor Act, in an attempt to aid collective action by employees, conferred great power and protection on the bargaining agent chosen by a majority of them. As individuals or small groups the employees cannot begin to possess the bargaining power of their representative in negotiating with the employer or in presenting their grievances to him. Nor may a minority choose another agent to bargain in their behalf. We need not pass on the Union's claim that it was not obliged to handle any grievances at all because we are clear that once it undertook to bargain or present grievances for some of the employees it represented it could not refuse to take similar action in good faith for other employees just because they were Negroes.

The respondents also argue that the complaint failed to set forth specific facts to support its general allegations of discrimination and that its dismissal is therefore proper. The decisive answer to this is that the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure do not require a claimant to set out in detail the facts upon which he bases his claim. To the contrary, all the Rules require is "a short and plain statement of the claim"[8] that will give the defendant fair notice of what the plaintiff's claim is and the grounds upon which it rests. The illustrative forms appended to the Rules plainly demonstrate this. Such simplified "notice pleading" is made possible by the liberal opportunity for discovery and the other pretrial procedures [48] established by the Rules to disclose more precisely the basis of both claim and defense and to define more narrowly the disputed facts and issues.[9] Following the simple guide of Rule 8 (f) that "all pleadings shall be so construed as to do substantial justice," we have no doubt that petitioners' complaint adequately set forth a claim and gave the respondents fair notice of its basis. The Federal Rules reject the approach that pleading is a game of skill in which one misstep by counsel may be decisive to the outcome and accept the principle that the purpose of pleading is to facilitate a proper decision on the merits. Cf. Maty v. Grasselli Chemical Co., 303 U. S. 197.

The judgment is reversed and the cause is remanded to the District Court for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

It is so ordered.

[1] 44 Stat. 577, as amended, 45 U. S. C. § 151 et seq.

[2] Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen & Enginemen, 323 U. S. 210; Graham v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen & Enginemen, 338 U. S. 232; Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Howard, 343 U. S. 768. Cf. Wallace Corp. v. Labor Board, 323 U. S. 248; Syres v. Oil Workers International Union, 350 U. S. 892.

[3]In full, § 3 First (i) reads:

"The disputes between an employee or group of employees and a carrier or carriers growing out of grievances or out of the interpretation or application of agreements concerning rates of pay, rules, or working conditions, including cases pending and unadjusted on the date of approval of this Act [June 21, 1934], shall be handled in the usual manner up to and including the chief operating officer of the carrier designated to handle such disputes; but, failing to reach an adjustment in this manner, the disputes may be referred by petition of the parties or by either party to the appropriate division of the Adjustment Board with a full statement of the facts and all supporting data bearing upon the disputes." 48 Stat. 1191, 45 U. S. C. § 153 First (i).

[4] For this reason the decision in Slocum v. Delaware, L. & W. R. Co., 339 U. S. 239, is not applicable here. The courts below also relied on Hayes v. Union Pacific R. Co., 184 F. 2d 337, cert. denied, 340 U. S. 942, but for the reasons set forth in the text we believe that case was decided incorrectly.

[5] See, e. g., Leimer v. State Mutual Life Assur. Co., 108 F. 2d 302; Dioguardi v. Durning, 139 F. 2d 774; Continental Collieries v. Shober, 130 F. 2d 631.

[6] Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co., 323 U. S. 192, 203.

[7] See Dillard v. Chesapeake & Ohio R. Co., 199 F. 2d 948; Hughes Tool Co. v. Labor Board, 147 F. 2d 69, 74.

[8] Rule 8 (a) (2).

[9] See, e. g., Rule 12 (e) (motion for a more definite statement); Rule 12 (f) (motion to strike portions of the pleading); Rule 12 (c) (motion for judgment on the pleadings); Rule 16 (pre-trial procedure and formulation of issues); Rules 26-37 (depositions and discovery); Rule 56 (motion for summary judgment); Rule 15 (right to amend).

10.2.7 Pleading and Practice After Conley 10.2.7 Pleading and Practice After Conley

Portions of this have been excerpted from

Ray Worthy Campbell, Getting a Clue: Two Stage Complaint Pleading as a Solution to the Conley-Iqbal Dilemma, 114 Penn St. L. Rev. 1191 (2010). Most citations have been omitted but are available in the original.

While the Federal Rules clearly marked a change in direction, the rules left room for interpretation. In particular, the exact nature of what constituted adequate pleading was inherently a bit hazy under Rule 8, given the rule’s careful avoidance of either of the words “fact” or “notice.” While Clark clearly favored a liberal notice pleading regime requiring little in the way of fact pleading, other scholars, as well as some judges and attorneys, preferred a more restrictive pleading regime. For nearly 20 years after the adoption of the rules, uncertainty remained about just how much factual detail was required under Rule 8’s “sort and plain statement” of the case.

The haziness was cleared in the landmark case of Conley v. Gibson. In this case, African American railroad workers brought a pro se claim that they had not been represented fairly by their union. The claim was dismissed by the lower courts for failure to state a claim, but the Supreme Court reversed. In language that opened the doors of the courthouse wide, the Court held that a complaint was sufficient “unless it appears beyond doubt that the plaintiff can prove no set of facts in support of his claims which would entitle him to relief.” The Court further held that so long as the defendant was on notice of the nature of the claim, specific facts need not be pleaded.

Conley was not briefed as a sufficiency of the pleadings case, and its sweeping language can be read as speaking to a demurrer type issue (do plaintiffs have a legal right?) as opposed to the sufficiency of the facts. Nonetheless, for a generation, Conley was understood to mean that the federal rules required far less than fact pleading.

Conley made hurdling the pleading barrier extraordinarily easy. Neoplatonic disputes about facts versus ultimate facts went away; technical failures in setting forth the claim rarely proved fatal. Within broad limits, plaintiffs got their day in court.

1. The Evolution of Litigation Under The Federal Rules

Taken in conjunction with the changes in joinder and discovery, notice pleading, as affirmed in Conley, ushered in a new era in how law suits were handled. Notice pleading made it easier for plaintiffs to launch the litigation process. The other reforms embodied in the Rules expanded the scope of that same litigation process. Unlike in times gone by, joinder allowed the inclusion of multiple defendants and multiple claims. Discovery became a new phase of litigation that absorbed massive amounts of lawyer time and client funds.

Pleading no longer served to define or control this process. Common law pleading had limited the subsequent litigation process to the precise legal issue identified at the outset; fact pleading set bounds on the facts that could be developed or proved. Notice pleading did not set comparable limits on the litigation process; indeed, the spirit of the Rules was to remove such constraints in order to allow parties to proceed into discovery and on to merits resolution.

In reducing the role of pleading, Clark seems to have expected that the path to the merits would prove short and efficient. Contrary to expectations, the path to merits resolution often proved long and expensive. The invention of photocopy machines and computers vastly expanded the scope of documents accessible to discovery requests. At first, the number and scope of interrogatories were limited only by the imagination of the litigating attorneys or the active intervention of judges, with no limits set by the rules themselves. Depositions similarly were unconstrained, subject to a judge choosing to intervene.

Over time, rather than being preparation to litigation, the discovery phase became the litigation. Trials became the exception, rather than the norm. Attorneys could spend their entire careers as “litigators” handling matters in federal court yet rarely, if ever, trying a case.

As it happened, lawyers did not abandon the “sporting theory” of litigation and were quick to take advantage of the new playing field created by the extended discovery phase. The temptation to engage in “sporting” litigation was only increased because this contest, unlike pleadings or trial itself, largely took place away from the supervision or even active awareness of the supervising judge.

Defendants joined in a proceeding were locked into a discovery process that often proved long and expensive, even when the defendant’s connection to the dispute was tangential. Discovery in a typical case includes interrogatories, document production and review, depositions and expert discovery. In multi-defendant cases, this pattern repeats across all defendants, and typically each defendant must not only engage in discovery related to itself and the plaintiff, but devote additional resources to monitor the discovery directed at its codefendants. Even if a tangential defendant is only along for the ride and can expect to win on the merits, it can be a high priced ticket.

To a significant extent, the evolution of federal practice since the 1970s has involved attempts to rein in this expansive discovery process. The “abuse” of discovery has been condemned. Judges have been encouraged to take a more active role in case management, with case conferences and discovery plans made the norm. Summary judgment, largely an innovative procedure at the times the Rules were established, took on greater prominence following the Trilogy cases. Default limits on the amount of discovery were imposed, both in limiting the default number of interrogatories and depositions, and in dialing back the scope of what was discoverable. All of this has happened, it should be noted, without any significant non-anecdotal evidence that the parties were engaging in disproportionately high levels of discovery.

Even so, the process can remain long and costly. For defendants, the first option for court-ordered exit in a well-pleaded case comes at summary judgment. Summary judgment presents, at best, a partial solution. The summary judgment stage typically is reached after the long and winding road of fact and expert discovery has been concluded, an expensive process (for cases that get into discovery, one study cited by the Twombly court shows that 90 percent of litigation costs were spent in the discovery process).

Reviewing an extensive record and preparing a summary judgment motion can also involve substantial expense. Since the judge cannot weigh the evidence in the place of the jury, even unpersuasive or conflicting evidence could suffice to keep a defendant in the case, and in complex cases confused witnesses or stray documents can create the kind of free floating factoids that might suffice to meet the summary judgment burden. Because denial of summary judgment is usually non-reviewable, some judges are reluctant to grant even meritorious summary judgment motions, preferring to let the parties make the case go away in settlement rather than risk reversal.

Of course, court ordered resolutions are not the only ways a defendant can be removed from a lawsuit. If discovery shows a defendant has no culpability, a plaintiff can voluntarily dismiss that defendant. On occasion, this happens. A plaintiff might prefer not to muddy its narrative by including excess defendants, or might wish to preserve credibility before a tribunal by releasing those clearly not liable. To the extent retaining a defendant in a lawsuit imposes financial costs, the plaintiff might wish to terminate those costs.

The most common way for lawsuits to be resolved, however, is not through voluntary dismissal but through settlement, in which some payment is made to the plaintiff in connection with securing a dismissal. Plaintiffs can seek to extract settlement payments from defendants who have been wrongly joined. Plaintiffs and defendants in multi-defendant litigation have a marked asymmetry of costs. For the plaintiff, marginal costs may not increase proportionally with the number of defendants. The plaintiff can amortize its investment across multiple defendants; a defendant must bear the cost of full litigation. At depositions, for example, the plaintiff only needs to send one attorney. By contrast, for any important deposition, each defendant might send an attorney, even if it is not their witness and even if they plan to ask no questions. In some multi-defendant cases, each deposition might involve a dozen attorneys, with only one representing the plaintiff, and the rest representing various defendants.

2. The 90’s And Beyond

Either side of the turn of the century saw extensive criticism, from academics, judges, legislators and practicing lawyers, of the litigation system spawned by the rules. The 1980s saw many federal judges imposing heightened pleading standards on selected cases. Spurred on by media coverage of a perhaps mythical litigation crisis, significant changes were made in the Rules to control discovery, and Congress imposed special heightened pleading requirements in securities cases. Almost beneath the radar, lower federal courts developed doctrines that had the effect of imposing heightened pleading requirements on certain types of cases.

B. Supreme Court Response To the Problems of Conley

In general, the Supreme Court remained a bulwark against changing pleading standards and on occasion reversed lower court rulings that sought to impose greater pleading requirements. In Leatherman v. Tarrant County Narcotics Intelligence & Coordination Unit, 507 U.S. 163 (1993), the Court, speaking through Chief Justice Rehnquist, declined to impose higher pleading standards for suits against municipalities in § 1983 cases. In Swierkiewicz v. Sorema, 534 U.S. 506 (2002), the Court, speaking through Justice Thomas, rebuffed an attempt to create a higher pleading standard in employment discrimination cases. Perhaps ironically, in light of later events, the Court stressed in these opinions that changes in pleading standards should come through the rulemaking process, and not through judge-made common law.

Then came the case of Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544 (2007). Twombly was an antitrust claim seeking class action status, and hoped to join as class members virtually all users of landline telephone services (at the time, virtually all U.S. households).

The factual history of the case is a bit complicated. At one time, “Ma Bell,” the American Telephone and Telegraph Co. (AT&T), had a near monopoly on US telephone services, both local and long distance (at the time, mobile phones were still, so far as the market was concerned, in their infancy). In 1982, AT&T agreed to divest itself of local landline services, splitting the local telephone services into seven regional “Baby Bell” companies, each of which effectively inherited the AT&T local monopoly in their service area.

Some ancient history may be in order for law students of today. At the time all this was happening, virtually all U.S. homes had a landline telephone. A copper wire ran to the consumer’s home or business, and calls were placed from and received on a telephone connected by a physical wire to the telephone network. Creating the network to reach every home was very expensive, but regulation and universal use guaranteed profits. At the time, while some special use situations employed mobile telephony – such as media outlets and some law enforcement – virtually no private consumers had access to mobile telephones. If they did, they were usually bulky and prone to technical problems. Also at this time long-distance calls were quite expensive (often several US dollars per minute) and thus highly profitable. After the 1982 split between local and long distance services, AT&T could offer long-distance services, which it dominated, but the Baby Bells could not.

In 1996, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 became law. An important goal of this legislation was to encourage competition for local services among the Baby Bells. The existing local monopolists were termed Incumbent Local Exchange Carriers (ILECs) under the bill; other companies that sought to compete with them were termed Competitive Local Exchange Carriers (CLECs). In order to make competition feasible, ILECs were required to share their lines at regulated rates with the CLECs, giving the CLECs time to build out their own wired systems. ILECS who cooperated by opening their markets to CLECs were given other benefits, such as the right to compete in the formerly closed-to-them long-distance market (which at the time was highly profitable). It was expected that the Baby Bells, ILECs in their own territories, would seek to become CLECs in neighboring and perhaps distant territories.

It didn’t happen. The ILECs stood pat in their own territories and made no effort to compete as CLECs with their fellow Baby Bells.

Sensing that a fix was in, the plaintiffs in Twombly filed a class action antitrust suit. The allegation was that the ILECs were conspiring to divide the markets, which would be a violation of the antitrust law, and had entered into an agreement to not compete as CLECs.

There was, however, no public evidence that this had, in fact, happened. What’s more, under existing antitrust law, if the case went to trial and there was no actual evidence of a conspiracy – as opposed to suspiciously parallel conduct – dismissal of the case was required.

Aside from the possibility that the defendants had entered into a conspiracy, there were possible reasons for not competing that might explain why not a single ILEC chose to become a CLEC. First, they may have just hoped that if they themselves did not start with price-cutting competition for local service, no one else would either. While this would involve an earnest hope that they would continue to enjoy monopoly standing in their home areas, it would not violate the antitrust laws as the essential element of an agreement would be missing. Another possibility would be that each of the ILECs looked at becoming a CLEC and decided that it would be a bad use of investment capital. In each new region, they would most likely be fighting for at best a respectable second place in the market while bearing costs as high as the market leaders. They might well conclude that there were higher profit businesses they could enter. Beyond that, it’s even possible that the ILEC executives, even if they didn’t fully appreciate the huge changes about to hit the telecommunications market, at least understood that with the birth of mobile telephones and the internet, that enough change was inevitable that making big bets on legacy technologies might not be a wise move.

Against this background the Twombly case reached the Supreme Court. At the time, the Conley rule that a complaint was sufficient “unless it appears beyond doubt that the plaintiff can prove no set of facts in support of his claims which would entitle him to relief” was in effect. While there was no smoking gun sufficient to prove a conspiracy alleged in the complaint, if one took the Conley language literally it certainly seemed possible that after enough discovery a set of facts might be unearthed that would entitle the plaintiffs to relief. A majority opinion by Justice Souter took a different approach:

“This case presents the antecedent question of what a plaintiff must plead in order to state a claim under § 1 of the Sherman Act. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a)(2) requires only “a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief,” in order to “give the defendant fair notice of what the ... claim is and the grounds upon which it rests,” Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 47, 78 S.Ct. 99, 2 L.Ed.2d 80 (1957). While a complaint attacked by a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss does not need detailed factual allegations, a plaintiff's obligation to provide the “grounds” of his “entitle[ment] to relief” requires more than labels and conclusions, and a formulaic recitation of the elements of a cause of action will not do. Factual allegations must be enough to raise a right to relief above the speculative level.

“In applying these general standards to a § 1 claim, we hold that stating such a claim requires a complaint with enough factual matter (taken as true) to suggest that an agreement was made. Asking for plausible grounds to infer an agreement does not impose a probability requirement at the pleading stage; it simply calls for enough fact to raise a reasonable expectation that discovery will reveal evidence of illegal agreement. And, of course, a well-pleaded complaint may proceed even if it strikes a savvy judge that actual proof of those facts is improbable, and “that a recovery is very remote and unlikely.” In identifying facts that are suggestive enough to render a § 1 conspiracy plausible, we have the benefit of the prior rulings and considered views of leading commentators, already quoted, that lawful parallel conduct fails to bespeak unlawful agreement. It makes sense to say, therefore, that an allegation of parallel conduct and a bare assertion of conspiracy will not suffice. Without more, parallel conduct does not suggest conspiracy, and a conclusory allegation of agreement at some unidentified point does not supply facts adequate to show illegality. Hence, when allegations of parallel conduct are set out in order to make a § 1 claim, they must be placed in a context that raises a suggestion of a preceding agreement, not merely parallel conduct that could just as well be independent action.

“The need at the pleading stage for allegations plausibly suggesting (not merely consistent with) agreement reflects the threshold requirement of Rule 8(a)(2) that the “plain statement” possess enough heft to “sho[w] that the pleader is entitled to relief.” A statement of parallel conduct, even conduct consciously undertaken, needs some setting suggesting the agreement necessary to make out a § 1 claim; without that further circumstance pointing toward a meeting of the minds, an account of a defendant's commercial efforts stays in neutral territory. An allegation of parallel conduct is thus much like a naked assertion of conspiracy in a § 1 complaint: it gets the complaint close to stating a claim, but without some further factual enhancement it stops short of the line between possibility and plausibility of “entitle[ment] to relief.”

* * *

“Thus, it is one thing to be cautious before dismissing an antitrust complaint in advance of discovery, but quite another to forget that proceeding to antitrust discovery can be expensive. As we indicated over 20 years ago in Associated Gen. Contractors of Cal., Inc. v. Carpenters, 459 U.S. 519, 528, n. 17, 103 S.Ct. 897, 74 L.Ed.2d 723 (1983), “a district court must retain the power to insist upon some specificity in pleading before allowing a potentially massive factual controversy to proceed.” That potential expense is obvious enough in the present case: plaintiffs represent a putative class of at least 90 percent of all subscribers to local telephone or high-speed Internet service in the continental United States, in an action against America's largest telecommunications firms (with many thousands of employees generating reams and gigabytes of business records) for unspecified (if any) instances of antitrust violations that allegedly occurred over a period of seven years.

“It is no answer to say that a claim just shy of a plausible entitlement to relief can, if groundless, be weeded out early in the discovery process through “careful case management,” given the common lament that the success of judicial supervision in checking discovery abuse has been on the modest side. And it is self-evident that the problem of discovery abuse cannot be solved by “careful scrutiny of evidence at the summary judgment stage,” much less “lucid instructions to juries;” the threat of discovery expense will push cost-conscious defendants to settle even anemic cases before reaching those proceedings. Probably, then, it is only by taking care to require allegations that reach the level suggesting conspiracy that we can hope to avoid the potentially enormous expense of discovery in cases with no “ ‘reasonably founded hope that the [discovery] process will reveal relevant evidence’ ” to support a § 1 claim.

“[Plaintiffs’] main argument against the plausibility standard at the pleading stage is its ostensible conflict with an early statement of ours construing Rule 8. Justice Black's opinion for the Court in Conley v. Gibson spoke not only of the need for fair notice of the grounds for entitlement to relief but of “the accepted rule that a complaint should not be dismissed for failure to state a claim unless it appears beyond doubt that the plaintiff can prove no set of facts in support of his claim which would entitle him to relief.” This “no set of facts” language can be read in isolation as saying that any statement revealing the theory of the claim will suffice unless its factual impossibility may be shown from the face of the pleadings; and the Court of Appeals appears to have read Conley in some such way when formulating its understanding of the proper pleading standard.

“On such a focused and literal reading of Conley's “no set of facts,” a wholly conclusory statement of claim would survive a motion to dismiss whenever the pleadings left open the possibility that a plaintiff might later establish some “set of [undisclosed] facts” to support recovery. So here, the Court of Appeals specifically found the prospect of unearthing direct evidence of conspiracy sufficient to preclude dismissal, even though the complaint does not set forth a single fact in a context that suggests an agreement. It seems fair to say that this approach to pleading would dispense with any showing of a “ ‘reasonably founded hope’ ” that a plaintiff would be able to make a case, see Dura, 544 U.S., at 347, 125 S.Ct. 1627 (quoting Blue Chip Stamps, 421 U.S., at 741, 95 S.Ct. 1917); Mr. Micawber's optimism would be enough.

“Seeing this, a good many judges and commentators have balked at taking the literal terms of the Conley passage as a pleading standard. See, e.g., Car Carriers, 745 F.2d, at 1106 (“Conley has never been interpreted literally” and, “[i]n practice, a complaint ... must contain either direct or inferential allegations respecting all the material elements necessary to sustain recovery under some viable legal theory” (internal quotation marks omitted; emphasis and omission in original)); Ascon Properties, Inc. v. Mobil Oil Co., 866 F.2d 1149, 1155 (C.A.9 1989) (tension between Conley's “no set of facts” language and its acknowledgment that a plaintiff must provide the “grounds” on which his claim rests); O'Brien v. DiGrazia, 544 F.2d 543, 546, n. 3 (C.A.1 1976) (“[W]hen a plaintiff ... supplies facts to support his claim, we do not think that Conley imposes a duty on the courts to conjure up unpleaded facts that might turn a frivolous claim of unconstitutional ... action into a substantial one”); McGregor v. Industrial Excess Landfill, Inc., 856 F.2d 39, 42–43 (C.A.6 1988) (quoting O'Brien's analysis); Hazard, From Whom No Secrets Are Hid, 76 Tex. L. Rev. 1665, 1685 (1998) (describing Conley as having “turned Rule 8 on its head”); Marcus, The Revival of Fact Pleading Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 86 Colum. L. Rev. 433, 463–465 (1986) (noting tension between Conley and subsequent understandings of Rule 8).

“We could go on, but there is no need to pile up further citations to show that Conley's “no set of facts” language has been questioned, criticized, and explained away long enough. To be fair to the Conley Court, the passage should be understood in light of the opinion's preceding summary of the complaint's concrete allegations, which the Court quite reasonably understood as amply stating a claim for relief. But the passage so often quoted fails to mention this understanding on the part of the Court, and after puzzling the profession for 50 years, this famous observation has earned its retirement. The phrase is best forgotten as an incomplete, negative gloss on an accepted pleading standard: once a claim has been stated adequately, it may be supported by showing any set of facts consistent with the allegations in the complaint. Conley, then, described the breadth of opportunity to prove what an adequate complaint claims, not the minimum standard of adequate pleading to govern a complaint's survival.”

A spirited defense by Justice Stevens attacked the approach of the majority, and questioned whether the rule announced applied only to large antitrust cases or to all cases filed in federal court.

The Twombly decision left many readers unclear as to what the opinion ultimately meant. Was it, as the dissent suggested, perhaps limited only to its own setting of massive antitrust cases? More fundamentally, what exactly does ‘plausible’ mean? Others struggled to reconcile the decision with the language and history of Rule 8(a)(2), since Twombly seemed in many ways to depart from both the language and previously understood spirit of the rule.

The level of confusion only increased when, only two weeks after Twombly, the Court cited Conley and its test favorably in Erickson v. Pardus, 551 U.S. 89 (2007). The Court disavowed any need to allege “specific facts,” stating that “fair notice” was enough. Twombly was not cited.

Into that confused state of affairs came the case that follows.

10.2.8 Ashcroft v. Iqbal 10.2.8 Ashcroft v. Iqbal

ASHCROFT, FORMER ATTORNEY GENERAL, et al. v. IQBAL et al.

No. 07-1015.

Argued December 10, 2008

Decided May 18, 2009

*665Former Solicitor General Garre argued the cause for petitioners. With him on the briefs were Assistant Attorney General Katsas, Deputy Assistant Attorney General Cohn, Curtis E. Gannon, Barbara L. Herwig, and Robert M. Loeb. Michael L. Martinez, David E. Bell, and Matthew F. Scarlato filed briefs for Dennis Hasty as respondent under this Court’s Rule 12.6 urging reversal. Brett M. Schuman, Lauren J. Resnick, and Thomas D Warren filed briefs for Michael Rolince et al. as respondents under this Court’s Rule 12.6 urging reversal.

Alexander A. Reinert argued the cause for respondents. With him on the brief for respondent Javaid Iqbal were Joan M. Magoolaghan, Elizabeth L. Koob, and Rima J. Oken*

delivered the opinion of the Court.

Javaid Iqbal (hereinafter respondent) is a citizen of Pakistan and a Muslim. In the wake of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks he was arrested in the United States on criminal charges and detained by federal officials. Respondent claims he was deprived of various constitutional protections while in federal custody. To redress the alleged deprivations, respondent filed a complaint against numerous federal officials, including John Ashcroft, the former Attorney General of the United States, and Robert Mueller, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Ashcroft and Mueller are the petitioners in the case now before us. As to these two petitioners, the complaint alleges that they adopted an unconstitutional policy that subjected respondent to harsh conditions of confinement on account of his race, religion, or national origin.

In the District Court petitioners raised the defense of qualified immunity and moved to dismiss the suit, contending the complaint was not sufficient to state a claim against them. The District Court denied the motion to dismiss, concluding the complaint was sufficient to state a claim despite petitioners’ official status at the times in question. Petitioners brought an interlocutory appeal in the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. The court, without discussion, assumed it had jurisdiction over the order denying the motion to dismiss; and it affirmed the District Court’s decision.

Respondent’s account of his prison ordeal could, if proved, demonstrate unconstitutional misconduct by some governmental actors. But the allegations and pleadings with respect to these actors are not before us here. This case instead turns on a narrower question: Did respondent, as the plaintiff in the District Court, plead factual matter that, if taken as true, states a claim that petitioners deprived him of his clearly established constitutional rights. We hold respondent’s pleadings are insufficient.

*667I

Following the 2001 attacks, the FBI and other entities within the Department of Justice began an investigation of vast reach to identify the assailants and prevent them from attacking anew. The FBI dedicated more than 4,000 special agents and 3,000 support personnel to the endeavor. By September 18 “the FBI had received more than 96,000 tips or potential leads from the public.” Dept, of Justice, Office of Inspector General, The September 11 Detainees: A Review of the Treatment of Aliens Held on Immigration Charges in Connection with the Investigation of the September 11 Attacks 1,11-12 (Apr. 2003), http://www.usdoj.gov/oig/ special/0306/full.pdf?bcsi_scan_61073ECQF74759AD=0& bcsi_scan_filename=full.pdf (as visited May 14, 2009, and available in Clerk of Court’s case file).

In the ensuing months the FBI questioned more than 1,000 people with suspected links to the attacks in particular or to terrorism in general. Id., at 1. Of those individuals, some 762 were held on immigration charges; and a 184-member subset of that group was deemed to be “of ‘high interest’ ” to the investigation. Id., at 111. The high-interest detainees were held under restrictive conditions designed to prevent them from communicating with the general prison population or the outside world. Id., at 112-113.

Respondent was one of the detainees. According to his complaint, in November 2001 agents of the FBI and Immigration and Naturalization Service arrested him on charges of fraud in relation to identification documents and conspiracy to defraud the United States. Iqbal v. Hasty, 490 F. 3d 143, 147-148 (CA2 2007). Pending trial for those crimes, respondent was housed at the Metropolitan Detention Center (MDC) in Brooklyn, New York. Respondent was designated a person “of high interest” to the September 11 investigation and in January 2002 was placed in a section of the MDC known as the Administrative Maximum Special Housing Unit *668(ADMAX SHU). Id., at 148. As the facility’s name indicates, the ADMAX SHU incorporates the maximum security conditions allowable under Federal Bureau of Prisons regulations. Ibid. ADMAX SHU detainees were kept in lock-down 23 hours a day, spending the remaining hour outside their cells in handcuffs and leg irons accompanied by a four-officer escort. Ibid.

Respondent pleaded guilty to the criminal charges, served a term of imprisonment, and was removed to his native Pakistan. Id., at 149. He then filed a Bivens action in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York against 34 current and former federal officials and 19 “John Doe” federal corrections officers. See Bivens v. Six Unknown Fed. Narcotics Agents, 403 U. S. 388 (1971). The defendants range from the correctional officers who had day-to-day contact with respondent during the term of his confinement, to the wardens of the MDC facility, all the way to petitioners — officials who were at the highest level of the federal law enforcement hierarchy. First Amended Complaint in No. 04-CV-1809 (JG)(JA), ¶¶ 10-11, App. to Pet. for Cert. 157a (hereinafter Complaint).

The 21-cause-of-action complaint does not challenge respondent’s arrest or his confinement in the MDC’s general prison population. Rather, it concentrates on his treatment while confined to the ADMAX SHU. The complaint sets forth various claims against defendants who are not before us. For instance, the complaint alleges that respondent’s jailors “kicked him in the stomach, punched him in the face, and dragged him across” his cell without justification, id., ¶ 113, at 176a; subjected him to serial strip and body-cavity searches when he posed no safety risk to himself or others, id., ¶¶ 143-145, at 182a; and refiised to let him and other Muslims pray because there would be “[n]o prayers for terrorists,” id., ¶ 154, at 184a.

The allegations against petitioners are the only ones relevant here. The complaint contends that petitioners desig*669nated respondent a person of high interest on account of his race, religion, or national origin, in contravention of the First and Fifth Amendments to the Constitution. The complaint alleges that “the [FBI], under the direction of Defendant MUELLER, arrested and detained thousands of Arab Muslim men ... as part of its investigation of the events of September 11.” Id., ¶ 47, at 164a. It further alleges that “[t]he policy of holding post-September-llth detainees in highly restrictive conditions of confinement until they were ‘cleared’ by the FBI was approved by Defendants ASHCROFT and MUELLER in discussions in the weeks after September 11, 2001.” Id., ¶ 69, at 168a. Lastly, the complaint posits that petitioners “each knew of, condoned, and willfully and maliciously agreed to subject” respondent to harsh conditions of confinement “as a matter of policy, solely on account of [his] religion, race, and/or national origin and for no legitimate penological interest.” Id., ¶ 96, at 172a-173a. The pleading names Ashcroft as the “principal architect” of the policy, id., ¶ 10, at 157a, and identifies Mueller as “instrumental in [its] adoption, promulgation, and implementation,” id., ¶ 11, at 157a.

Petitioners moved to dismiss the complaint for failure to state sufficient allegations to show their own involvement in clearly established unconstitutional conduct. The District Court denied their motion. Accepting all of the allegations in respondent’s complaint as true, the court held that “it cannot be said that there [is] no set of facts on which [respondent] would be entitled to relief as against” petitioners. Id., at 136a-137a (relying on Conley v. Gibson, 355 U. S. 41 (1957)). Invoking the collateral-order doctrine petitioners filed an interlocutory appeal in the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. While that appeal was pending, this Court decided Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U. S. 544 (2007), which discussed the standard for evaluating whether a complaint is sufficient to survive a motion to dismiss.

*670The Court of Appeals considered Twombly’s applicability to this case. Acknowledging that Twombly retired the Conley no-set-of-facts test relied upon by the District Court, the Court of Appeals’ opinion discussed at length how to apply this Court’s “standard for assessing the adequacy of pleadings.” 490 F. 3d, at 155. It concluded that Twombly called for a “flexible ‘plausibility standard,’ which obliges a pleader to amplify a claim with some factual allegations in those contexts where such amplification is needed to render the claim plausible” Id., at 157-158. The court found that petitioners’ appeal did not present one of “those contexts” requiring amplification. As a consequence, it held respondent’s pleading adequate to allege petitioners’ personal involvement in discriminatory decisions which, if true, violated clearly established constitutional law. Id., at 174.

Judge Cabranes concurred. He agreed that the majority’s “discussion of the relevant pleading standards reflected] the uneasy compromise . .. between a qualified immunity privilege rooted in the need to preserve the effectiveness of government as contemplated by our constitutional structure and the pleading requirements of Rule 8(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.” Id., at 178 (internal quotation marks and citations omitted). Judge Cabranes nonetheless expressed concern at the prospect of subjecting high-ranking Government officials — entitled to assert the defense of qualified immunity and charged with responding to “a national and international security emergency unprecedented in the history of the American Republic” — to the burdens of discovery on the basis of a complaint as nonspecific as respondent’s. Id., at 179. Reluctant to vindicate that concern as a member of the Court of Appeals, ibid., Judge Cabranes urged this Court to address the appropriate pleading standard “at the earliest opportunity,” id., at 178. We granted certiorari, 554 U. S. 902 (2008), and now reverse.

*671II

We first address whether the Court of Appeals had subject-matter jurisdiction to affirm the District Court’s order denying petitioners’ motion to dismiss. Respondent disputed subject-matter jurisdiction in the Court of Appeals, but the court hardly discussed the issue. We are not free to pretermit the question. Subject-matter jurisdiction cannot be forfeited or waived and should be considered when fairly in doubt. Arbaugh v.Y & H Corp., 546 U. S. 500, 514 (2006) (citing United States v. Cotton, 535 U. S. 625, 630 (2002)). According to respondent, the District Court’s order denying petitioners’ motion to dismiss is not appealable under the collateral-order doctrine. We disagree.

A

With exceptions inapplicable here, Congress has vested the courts of appeals with “jurisdiction of appeals from all final decisions of the district courts of the United States.” 28 U. S. C. § 1291. Though the statute’s finality requirement ensures that “interlocutory appeals — appeals before the end of district court proceedings — are the exception, not the rule,” Johnson v. Jones, 515 U. S. 304, 309 (1995), it does not prevent “review of all prejudgment orders,” Behrens v. Pelletier, 516 U. S. 299, 305 (1996). Under the collateral-order doctrine a limited set of district-court orders are reviewable “though short of final judgment.” Ibid. The orders within this narrow category “are immediately appeal-able because they ‘finally determine claims of right separable from, and collateral to, rights asserted in the action, too important to be denied review and too independent of the cause itself to require that appellate consideration be deferred until the whole case is adjudicated.’” Ibid, (quoting Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp., 337 U. S. 541, 546 (1949)).

A district-court decision denying a Government officer’s claim of qualified immunity can fall within the narrow class *672of appealable orders despite “the absence of a final judgment.” Mitchell v. Forsyth, 472 U. S. 511, 530 (1985). This is so because qualified immunity — which shields Government officials “from liability for civil damages insofar as their conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights,” Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U. S. 800, 818 (1982) — is both a defense to liability and a limited “entitlement not to stand trial or face the other burdens of litigation.” Mitchell, 472 U. S., at 526. Provided it “turns on an issue of law,” id., at 530, a district-court order denying qualified immunity “ ‘conclusively determine^]’ ” that the defendant must bear the burdens of discovery; is “conceptually distinct from the merits of the plaintiff’s claim”; and would prove “effectively unreviewable on appeal from a final judgment,” id., at 527-528 (citing Cohen, supra, at 546). As a general matter, the collateral-order doctrine may have expanded beyond the limits dictated by its internal logic and the strict application of the criteria set out in Cohen. But the applicability of the doctrine in the context of qualified-immunity claims is well established; and this Court has been careful to say that a district court’s order rejecting qualified immunity at the motion-to-dismiss stage of a proceeding is a “final decision” within the meaning of § 1291. Behrens, 516 U. S., at 307.

B