7 Subject Matter Jurisdiction 7 Subject Matter Jurisdiction

7.1 Subject Matter Jurisdiction Wordcloud 7.1 Subject Matter Jurisdiction Wordcloud

7.2 Introduction to Subject Matter Jurisdiction 7.2 Introduction to Subject Matter Jurisdiction

7.2.1 Overview - The Constitutional Basis 7.2.1 Overview - The Constitutional Basis

Federal subject matter jurisdiction involves a fundamental aspect of American constitutional governance – the federal government is a government of limited powers. Put differently, the federal government in the United States can only exercise those powers granted to it under the Constitution. While in many areas constitutional amendments such as the 14th Amendment and judicial interpretations have expanded federal power so as to make it seem almost unlimited, where federal courts are concerned the limitations on federal power remain very much alive.

The U.S. Constitution sets forth the judicial function of the federal government in Article 3. Article 3, Section 2, lists the kinds of cases the federal government may entertain in its courts. No cases can be heard by federal courts that are not included in the categories identified in Article 3, Section 2.

Unlike the Constitutional limitations on judicial power that we have looked at previously (personal jurisdiction and notice), subject matter jurisdiction is not waivable by the parties. The parties cannot consent to subject matter jurisdiction when it is absent or doubtful. Put differently, the interest here is in limiting the reach of the federal government to the Constitutional scope, and it is not within the power of any litigant, even the government, to extend that power through consent. If at any stage of litigation a lack of subject matter jurisdiction is recognized, the case must be dismissed.

We will not examine every type of case that Section 2 authorizes for federal court. We will limit our review to federal question cases, and cases that involve diversity or alienage jurisdiction. In addition, we will look at supplemental jurisdiction, which is when the court hearing a case that has a basis for subject matter jurisdiction over some counts can exercise jurisdiction over aspects of the case or controversy that might not on their own qualify for federal jurisdiction, and removal processes, which allow cases to be moved from state courts to federal courts in certain situations.

As we have seen before, subject matter jurisdiction involves Constitutional and statutory layers. In addition to the Constitutional grant, there must be an enabling statute which grants and sometimes limits the power of federal courts to hear cases that fall within the Article 3, Section 2 grant.

One term that might prove confusing in this context is 'general jurisdiction.' You remember that term from our discussion of personal jurisdiction. Here, it means something very different. Just as federal courts are courts of 'limited jurisdiction,' state court systems are courts of 'general jurisdiction' in the sense that their reach is not limited by a Constitutional grant. Unless a statute or the Constitution takes a case away from a state court, the state courts have the power to resolve the case.

To further complicate things, while state court systems are courts of general jurisdiction, not every court in a state court system will be one of general jurisdiction. Some courts in the state system have a limited purpose - hearing divorce cases or traffic violations, for example. Often, the main state trial courts - sometimes called Circuit Courts or Superior Courts or Courts of Common Pleas, although to be extra confusing New York calls its trial courts Supreme Courts - are referred to as courts of general jurisdiction because they are empowered under state law to hear a full range of cases.

Don't let the terms lead you astray. Keep in mind the basic principle - federal courts are limited in their power, and can only hear certain kinds of cases. State courts, on the other hand, can hear both federal and state cases. In fact, they can hear any case that is not reserved to the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal courts. There are a few such areas, but they are the exception. (Exclusive areas of federal jurisdiction are copyright cases, admiralty cases, lawsuits involving the military, immigration laws, and bankruptcy proceedings.)

As a practical matter, this means that state and federal courts often have what is called concurrent jurisdiction. Their jurisdictions overlap, and many cases can be heard in either federal court or state court. State law cases, as we will see in this section, can be heard in federal court if diversity or alienage jurisdiction exists. In addition, even the claim on its own does not meet the requirements of diversity or alienage jurisdiction, so-called 'supplemental jurisdiction' allows claims that arise in the same case or controversy to be in federal court alongside claims for which there is a federal jurisdictional basis. In other cases, even though a federal jurisdictional basis exists, the parties may simply prefer for any number of reasons to proceed in state court on either state or federal claims.

This means that litigants often have the ability to select a forum. Sometimes, pejoratively, this is called forum shopping. Whether you view it as a good thing, a bad thing, or just an inevitable thing in a system that allows multiple courts to hear the same case, it is a feature of the US system. Understanding federal subject matter jurisdiction in all its complexity is an essential step to knowing when and how forums can be selected.

In the section that follows, we will explore all that in more detail. For the most part, you will find this complicated with lots of rules, but not hard to understand. Keep in mind that forum selection can be an important and sometimes outcome-determining tool in the litigator's toolbox, so this is worth understanding well.

7.2.2 Article III, Section 2 7.2.2 Article III, Section 2

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls; to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; to Controversies between two or more States; between a State and Citizens of another State; between Citizens of different States; between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

7.2.3 Capron v. Van Noorden, 6 U.S. (2 Cranch) 126 (1804) 7.2.3 Capron v. Van Noorden, 6 U.S. (2 Cranch) 126 (1804)

Feb Term 1804

Opinion

A plaintiff may assign for error the want of jurisdiction in that court to which he has chosen to resort.

A party may take advantage of an error in his favor, if it be an error of the Court.

The Courts of the U.S. have not jurisdiction unless the record shews that the parties are citizens of different states, or that one is an alien, &c.

Error to the Circuit Court of North Carolina. The proceedings stated Van Noorden to be late of Pitt county, but did not allege Capron, the plaintiff, to be an alien, nor a citizen of any state, nor the place of his residence.

Upon the general issue, in an action of trespass on the case, a verdict was found for the defendant, Van Noorden, upon which judgment was rendered.

The writ of Error was sued out by Capron, the plaintiff below, who assigned for error, among other things, first “That the circuit court aforesaid is a court of limited jurisdiction, and that by the record aforesaid it doth not appear, as it ought to have done, that either the said George Capron, or the said Hadrianus Van Noorden was an alien at the time of the commencement of said suit, or at any other time, or that one of the said parties was at that or any other time, a citizen of the state of North Carolina where the suit was brought, and the other a citizen of another state; or that they the said George and Hadrianus were for any cause whatever, persons within the jurisdiction of the said court, and capable of suing and being sued there.”

And secondly, “That by the record aforesaid it manifestly appeareth that the said Circuit Court had not any jurisdiction of the cause aforesaid, nor ought to have held plea thereof, or given judgment therein, but ought to have dismissed the same, whereas the said Court hath proceeded to final judgment therein.”

Harper, for the plaintiff in error, stated the only question to be whether the plaintiff had a right to assign for error, the want of jurisdiction in that Court to which he had chosen to resort.

It is true, as a general rule, that a man cannot reverse a judgment for error in process or delay, unless he can shew that the error was to his disadvantage; but it is also a rule, that he may reverse a judgment for an error of the Court, even though it be for his advantage. As if a verdict be found for the debt, damages, and costs; and the judgment be only for the debt and damages, the defendant may assign for error that the judgment was not also for costs, although the error is for his advantage.

Here it was the duty of the Court to see that they had jurisdiction, for the consent of parties could not give it.

It is therefore an error of the Court, and the plaintiff has a right to take advantage of it. 2 Bac.Ab.Tit. Error. (K.4.)—8 Co. 59.(a) Beecher's case.—1 Roll.Ab. 759—Moor 692.—1 Lev. 289. Bernard v. Bernard.

The defendant in error did not appear, but the citation having been duly served, the judgment was reversed.

7.2.4 Notes on Capron v. Van Noorden 7.2.4 Notes on Capron v. Van Noorden

1. Capron v. Van Noorden. The antiquated language and differences in the judicial system in Capron v. Van Noorden can make it a bit difficult to get started with the case. The facts are quite simple, though: the plaintiff filed a case in federal court, making inadequate jurisdictional allegations; the trial court accepted the case and ruled for the defendant; the plaintiff then sought to have the suit dismissed on grounds that there was never federal subject matter jurisdiction. Even though the plaintiff contributed mightily to the situation, in the end it was the duty of the court to establish that federal subject matter jurisdiction existed. As the allegations were inadequate, there was no federal subject matter jurisdiction, and the case had to be dismissed. Because the court never had subject matter jurisdiction, the proceedings in the trial court were void and of no effect.

2. Basic Principles. Some very basic principles are present in Capron v. Van Noorden. First, a federal court must have subject matter jurisdiction or it cannot hear a case - even if the parties wish it to. Second, the basis for jurisdiction must appear in the pleadings or the record; the court cannot assume it or rely upon conclusory allegations. Third, it is the responsibility of the court to establish subject matter jurisdiction. It must, own its own, sua sponte, take the steps necessary to determine jurisdiction and to dismiss the case if jurisdiction is not shown. The parties can raise the issue at any time, and the court should address it on its own if the parties fail to note the problem.

7.2.5 Challenging Subject Matter Jurisdiction 7.2.5 Challenging Subject Matter Jurisdiction

It should be clear from Capron that a lack of subject matter jurisdiction can be made at any time during the original litigation - even when the case is on appeal at the U.S. Supreme Court. Indeed, if no litigant raises the issue, the court can and should examine the issue on its own. As subject matter jurisdiction cannot be waived, there is no special procedure to avoid waiver. At any point in the litigation, the case must be dismissed if there is no subject matter jurisdiction. You will see examples of that as we go forward in this section.

One might wonder if, on occasion, litigants might be tempted to trick the other side by litigating a case where they know that subject matter jurisdiction does not exist. If they win, and the other side does not recognize the jurisdictional defect, they stay silent and keep the benefit of the win; if they lose, they can assert the lack of subject matter jurisdiction, the case is dismissed, and they are free to try again. What if defendants wait until after a statute of limitations has passed before revealing the lack of subject matter jurisdiction?

Something like this arose in Wojan v. General Motors Corp., 851 F.2d 969 (7th Cir.1988). In Wojan, the plaintiff, a resident of Michigan, filed suit in Illinois, stating in its jurisdictional statement that General Motors was incorporated in Delaware and licensed to do business as an out-of-state corporation in Illinois. It did not mention where General Motors had its principal place of business, which quite famously is in Michigan. In its answer, General Motors admitted that it was incorporated in Delaware and expressed a lack of knowledge as to plaintiff's residence. Neither the judge nor the plaintiff apparently noticed that General Motors said nothing about its principal place of business, which as we will see shortly is relevant to establishing diversity jurisdiction for corporations. General Motors later, in its answer, admitted the existence of diversity jurisdiction, notwithstanding that few U.S. corporations are more firmly and widely associated with their principal place of business than General Motors is with Michigan and the automobile manufacturing center of Detroit, also known as Motor City or Motown.

After five and a half years of litigation, and apparently having had a long-deferred moment of recognition when a new associate on the case asked why there was subject matter jurisdiction, General Motors finally asserted that there was no subject matter jurisdiction, and the case was dismissed without prejudice allowing, in theory, Wojan to refile in state court. Without researching what statute of limitations applied to such a case in Illinois in the 1980s, it seems highly likely that the applicable statute of limitations had passed when the jurisdictional defect was raised with the court almost eight years after the original accident, and so Wojan's litigation was likely at an end except for a possible malpractice claim against her lawyer.

Wojan sought Rule 11 sanctions against General Motors for admitting subject matter jurisdiction when it should have denied jurisdiction. While the Seventh Circuit noted that the General Motors lawyers (and the trial judge) were not without fault, it held that it was the duty of the plaintiff to establish the basis for subject matter jurisdiction at the outset, and that awaiting General Motors' response on a jurisdictional allegation that a moment's thought would have shown defective was not reasonable. One can imagine situations where deliberate and cunning failure to alert the court to a lack of subject matter jurisdiction could lead to ethical concerns or sanctions (in Wojan the defense lawyers seem to have been more asleep than intentionally deceptive), but it is clear that in every case, notwithstanding the equities, if subject matter jurisdiction is lacking the court has no choice and has to dismiss the case.

What happens after a case is over? Can an apparent lack of subject matter jurisdiction be used to set aside a judgment as void upon a collateral attack as can be done when personal jurisdiction is lacking?

The answer turns out to be a bit complicated. When the case has been adversely litigated between the parties in federal court, it seems fairly clear that the judgment cannot be challenged collaterally on the grounds that there was no subject matter jurisdiction. In Chicot County Drainage Distr. v. Baxter State Bank, 308 U.S. 371 (1940), a federal statute apparently in effect at the time the case was tried provided a basis for federal subject matter jurisdiction. No one, therefore, questioned subject matter jurisdiction and judgment was entered. When that federal statute was found to be unconstitutional, removing the jurisdictional basis, an effort was made to collaterally attack the judgment. The Court held that the subject matter jurisdiction could not be collaterally attacked but should have been litigated in the first proceeding.

The situation gets a bit murky when the first case involves a default judgment (and a bit murkier because people differ on whether to characterize Chicot as a default case, given that it was actively litigated but where the parties bringing the collateral challenge had not actually appeared in the first litigation). Remember that, whether anyone actively litigates the case or not, the federal court should always determine that it has subject matter jurisdiction, so in theory there should be a determination as to subject matter jurisdiction in every case. Perhaps as a result of this, while there is some academic support for being open to collateral attacks in some situations (see Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 65) courts in general do not set aside judgments based on collateral attacks on subject matter jurisdiction.

7.3 Diversity and Alienage As a Basis For Subject Matter Jurisdiction 7.3 Diversity and Alienage As a Basis For Subject Matter Jurisdiction

Please note that in the section that follows we are talking about cases that arise under state law. What claims, based on state law, nonetheless have a right to be decided in federal court? (Remember that federal law can be created by the federal legislature and to a limited extent by federal courts. Parallel to that state legislatures and state courts can create law that is binding within their states.) The jurisdictional answer with regard to original (versus supplemental) jurisdiction has to do with where the parties are from. The story begins with the diversity and alienage clauses of Article III, Section 2, but the implementation of those grants of constitutional authority by the following statute also matters.

7.3.1 28 U.S. Code § 1332. Diversity of citizenship; amount in controversy; costs 7.3.1 28 U.S. Code § 1332. Diversity of citizenship; amount in controversy; costs

(a) The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of all civil actions where the matter in controversy exceeds the sum or value of $75,000, exclusive of interest and costs, and is between—

(1) citizens of different States;

(2) citizens of a State and citizens or subjects of a foreign state, except that the district courts shall not have original jurisdiction under this subsection of an action between citizens of a State and citizens or subjects of a foreign state who are lawfully admitted for permanent residence in the United States and are domiciled in the same State;

(3) citizens of different States and in which citizens or subjects of a foreign state are additional parties; and

(4) a foreign state, defined in section 1603(a) of this title, as plaintiff and citizens of a State or of different States.

(b) Except when express provision therefor is otherwise made in a statute of the United States, where the plaintiff who files the case originally in the Federal courts is finally adjudged to be entitled to recover less than the sum or value of $75,000, computed without regard to any setoff or counterclaim to which the defendant may be adjudged to be entitled, and exclusive of interest and costs, the district court may deny costs to the plaintiff and, in addition, may impose costs on the plaintiff.

(c) For the purposes of this section and section 1441 of this title—

(1) a corporation shall be deemed to be a citizen of every State and foreign state by which it has been incorporated and of the State or foreign state where it has its principal place of business, except that in any direct action against the insurer of a policy or contract of liability insurance, whether incorporated or unincorporated, to which action the insured is not joined as a party-defendant, such insurer shall be deemed a citizen of—

(A) every State and foreign state of which the insured is a citizen;

(B) every State and foreign state by which the insurer has been incorporated; and

(C) the State or foreign state where the insurer has its principal place of business; and

(2) the legal representative of the estate of a decedent shall be deemed to be a citizen only of the same State as the decedent, and the legal representative of an infant or incompetent shall be deemed to be a citizen only of the same State as the infant or incompetent.

(d) [Omitted for Now]

7.3.2 Determining Domicile 7.3.2 Determining Domicile

7.3.2.1 Mas v. Perry 7.3.2.1 Mas v. Perry

Jean Paul MAS and Judy Mas, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. Oliver H. PERRY, Defendant-Appellant.

No. 73-3008

Summary Calendar.*

United States Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit.

Feb. 22, 1974.

Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc Denied April 3, 1974.

*1398Sylvia Roberts, John L. Avant, Baton Rouge, La., for defendant-appellant.

Dennis R. Whalen, Baton Rouge, La., for plaintiffs-appellees.

Before WISDOM, AINSWORTH and CLARK, Circuit Judges.

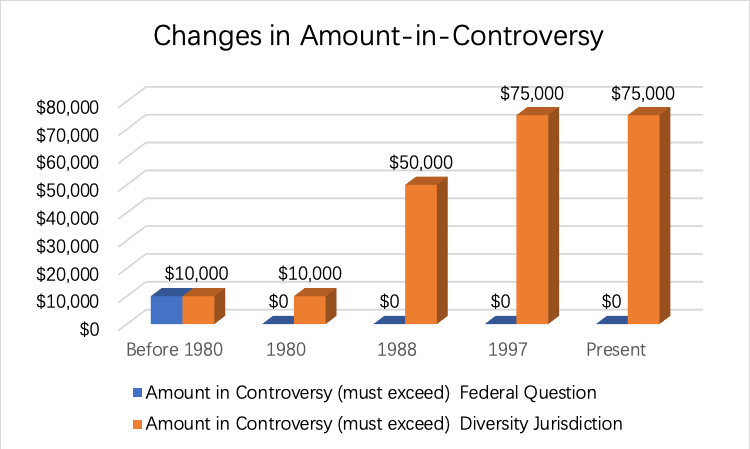

This case presents questions pertaining to federal diversity jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1332, which, pursuant to article III, section II of the Constitution, provides for original jurisdiction in federal district courts of all civil actions that are between, inter alia, citizens of different States or citizens of a State and citizens of foreign states and in which the amount in controversy is more than $10,000.

Appellees Jean Paul Mas, a citizen of France, and Judy Mas were married at her home in Jackson, Mississippi. Prior to their marriage, Mr. and Mrs. Mas were graduate assistants, pursuing coursework as well as performing teaching duties, for approximately nine months and one year, respectively, at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Shortly after their marriage, they returned to Baton Rouge to resume their duties as graduate assistants at LSU. They remained in Baton Rouge for approximately two more years, after which they moved to Park Ridge, Illinois. At the time of the trial in this case, it was their intention to return to Baton Rouge while Mr. Mas finished his studies for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mr. and Mrs. Mas were undecided as to where they would reside after that.

Upon their return to Baton Rouge after their marriage, appellees rented an apartment from appellant Oliver H. Perry, a citizen of Louisiana. This appeal arises from a final judgment entered on a jury verdict awarding $5,000 to Mr. Mas and $15,000 to Mrs. Mas for damages incurred by them as a result of the discovery that their bedroom and bathroom contained “two-way” mirrors and that they had been watched through them by the appellant during three of the first four months of their marriage.

At the close of the appellees’ case at trial, appellant made an oral motion to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction.1 The motion was denied by the district court. Before this Court, appellant challenges the final judgment below solely on jurisdictional grounds, contending that appel-lees failed to prove diversity of citizenship among the parties and that the requisite jurisdictional amount is lacking with respect to Mr. Mas. Finding no merit to these contentions, we affirm. Under section 1332(a)(2), the federal judicial power extends to the claim of Mr. Mas, a citizen of France, against the appellant, a citizen of Louisiana. Since we conclude that Mrs. Mas is a citizen of Mississippi for diversity purposes, the district court also properly had jurisdiction under section 1332(a) (1) of her claim.

It has long been the general rule that complete diversity of parties is *1399required in order that diversity jurisdiction obtain; that is, no party on one side may be a citizen of the same State as any party on the other side. Strawbridge v. Curtiss, 7 U.S. (3 Cranch) 267, 2 L.Ed. 435 (1806); see eases cited in 1 W. Barron & A. Holtzoff, Federal Practice and Procedure § 26, at 145 n. 95 (Wright ed. 1960). This determination of one’s State citizenship for diversity purposes is controlled by federal law, not by the law of any State. 1 J. Moore, Moore’s Federal Practice j[ 0.74 [1], at 707.1 (1972). As is the case in other areas of federal jurisdiction, the diverse citizenship among adverse parties must be present at the time the complaint is filed. Mullen v. Torrance, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 537, 539, 6 L.Ed. 154, 155 (1824); Slaughter v. Toye Bros. Yellow Cab Co., 5 Cir., 1966, 359 F.2d 954, 956. Jurisdiction is unaffected by subsequent changes in the citizenship of the parties. Morgan’s Heirs v. Morgan, 15 U.S. (2 Wheat.) 290, 297, 4 L.Ed. 242, 244 (1817); Clarke v. Mathewson, 37 U.S. (12 Pet.) 164, 171, 9 L.Ed. 1041, 1044 (1838); Smith v. Sperling, 354 U.S. 91, 93 n. 1, 77 S.Ct. 1112, 1113 n. 1, 1 L.Ed. 2d 1205 (1957). The burden of pleading the diverse citizenship is upon the party invoking federal jurisdiction, see Cameron v. Hodges, 127 U.S. 322, 8 S.Ct. 1154, 32 L.Ed. 132 (1888); and if the diversity jurisdiction is properly challenged, that party also bears the burden of proof, McNutt v. General Motors Acceptance Corp., 298 U.S. 178, 56 S.Ct. 780, 80 L.Ed. 1135 (1936); Welsh v. American Surety Co. of New York, 5 Cir., 1951, 186 F.2d 16, 17.

To be a citizen of a State within the meaning of section 1332, a natural person must be both a citizen of the United States, see Sun Printing & Publishing Association v. Edwards, 194 U.S. 377, 383, 24 S.Ct. 696, 698, 48 L.Ed. 1027 (1904); U.S.Const. Amend. XIV, § 1, and a domiciliary of that State. See Williamson v. Osenton, 232 U.S. 619, 624, 34 S.Ct. 442, 58 L.Ed. 758 (1914); Stine v. Moore, 5 Cir., 1954, 213 F.2d 446, 448. For diversity purposes, citizenship means domicile; mere residence in the State is not sufficient. See Wolfe v. Hartford Life & Annuity Ins. Co., 148 U.S. 389, 13 S.Ct. 602, 37 L.Ed. 493 (1893); Stine v. Moore, 5 Cir., 1954, 213 F.2d 446, 448.

A person’s domicile is the place of “his true, fixed, permanent home and principal establishment, and to which he has the intention of returning whenever he is absent therefrom . ” Stine v. Moore, 5 Cir., 1954, 213 F.2d 446, 448. A change of domicile may be effected only by a combination of two elements: (a) taking up residence in a different domicile with (b) the intention to remain there. Mitchell v. United States, 88 U.S. (21 Wall.) 350, 22 L.Ed. 584 (1875); Sun Printing & Publishing Association v. Edwards, 194 U.S. 377, 24 S.Ct. 696, 48 L.Ed. 1027 (1904).

It is clear that at the time of her marriage, Mrs. Mas was a domiciliary of the State of Mississippi. While it is generally the case that the domicile of the wife — and, consequently, her State citizenship for purposes of diversity jurisdiction — is deemed to be that of her husband, 1 J. Moore, Moore’s Federal Practice ¶ 0.74 [6. — 1], at 708.51 (1972), we find no precedent for extending this concept to the situation here, in which the husband is a citizen of a foreign state but resides in the United States. Indeed, such a fiction would work absurd results on the facts before us. If Mr. Mas were considered a domiciliary of France — as he would be since he had lived in Louisiana as a student-teaching assistant prior to filing this suit, see Chicago & Northwestern Railway Co. v. Ohle, 117 U.S. 123, 6 S.Ct. 632, 29 L.Ed. 837 (1886); Bell v. Milsak, W.D.La., 1952, 106 F.Supp. 219— then Mrs. Mas would also be deemed a domiciliary, and thus, fictionally at least, a citizen of France. She would not be a citizen of any State and could *1400not sue in a federal court on that basis; nor could she invoke the alienage jurisdiction to bring her claim in federal court, since she is not an alien. See C. Wright, Federal Courts 80 (1970). On the other hand, if Mrs. Mas’s domicile were Louisiana, she would become a Louisiana citizen for diversity purposes and could not bring suit with her husband against appellant, also a Louisiana citizen, on the basis of diversity jurisdiction. These are curious results under a rule arising from the theoretical identity of person and interest of the married couple. See Linscott v. Linscott, S.D.Iowa, 1951, 98 F.Supp. 802, 804; Juneau v. Juneau, 227 La. 921, 80 So.2d 864, 867 (1954).

An American woman is not deemed to have lost her United States citizenship solely by reason of her marriage to an alien. 8 U.S.C. § 1489. Similarly, we conclude that for diversity purposes a woman does not have her domicile or State citizenship changed solely by reason of her marriage to an alien.

Mrs. Mas’s Mississippi domicile was disturbed neither by her year in Louisiana prior to her marriage nor as a result of the time she and her husband spent at LSU after their marriage, since for both periods she was a graduate assistant at LSU. See Chicago & Northwestern Railway Co. v. Ohle, 117 U.S. 123, 6 S.Ct. 632, 29 L.Ed. 837 (1886). Though she testified that after her marriage she had no intention of returning to her parents' home in Mississippi, Mrs. Mas did not effect a change of domicile since she and Mr. Mas were in Louisiana only as students and lacked the requisite intention to remain there. See Hendry v. Masonite Corp., 5 Cir., 1972, 455 F.2d 955, cert. denied, 409 U. S. 1023, 93 S.Ct. 464, 34 L.Ed.2d 315. Until she acquires a new domicile, she remains a domiciliary, and thus a citizen, of Mississippi. See Mitchell v. United States, 88 U.S. (21 Wall.) 350, 352, 22 L.Ed. 584, 587-588 (1875); Sun Printing & Publishing Association v. Edwards, 194 U.S. 377, 383, 24 S.Ct. 696, 698, 48 L.Ed. 1027 (1904); Welsh v. American Security Co. of New York, 5 Cir., 1951, 186 F.2d 16, 17.2

Appellant also contends that Mr. Mas’s claim should have been dismissed for failure to establish the requisite jurisdictional amount for diversity cases of more than $10,000. In their complaint Mr. and Mrs. Mas alleged that they had each been damaged in the amount of $100,000. As we have noted, Mr. Mas ultimately recovered $5,000.

It is well settled that the amount in controversy is determined by the amount claimed by the plaintiff in good faith. KVOS, Inc. v. Associated Press, 299 U.S. 269, 57 S.Ct. 197, 81 L. Ed. 183 (1936); 1 J. Moore, Moore’s Federal Practice ¶ 0.92 [1] (1972). Federal jurisdiction is not lost because a judgment of less than the jurisdictional amount is awarded. Jones v. Landry, 5 Cir., 1967, 387 F.2d 102; C. Wright, Federal Courts 111 (1970). That Mr. Mas recovered only $5,000 is, therefore, not compelling. As the Supreme Court stated in St. Paul Mercury Indemnity Co. v. Red Cab Co., 303 U.S. 283, 288-290, 58 S.Ct. 586, 590-591, 82 L.Ed. 845:

[T]he sum claimed by the plaintiff controls if the claim is apparently made in good faith.

It must appear to a legal certainty that the claim is really for less than the jurisdictional amount to justify dismissal. The inability of the plain*1401tiff to recover an amount adequate give the court jurisdiction does not show his bad faith or oust the jurisdiction. . to

. . . His good faith in choosing the federal forum is open to challenge not only by resort to the face of his complaint, but by the facts disclosed at trial, and if from either source it is clear that his claim never could have amounted to the sum necessary to give jurisdiction there is no injustice in dismissing the suit.

Having heard the evidence presented at the trial, the district court concluded that the appellees properly met the requirements of section 1332 with respect to jurisdictional amount. Upon examination of the record in this case, we are also satisfied that the requisite amount was in controversy. See Jones v. Landry, 5 Cir., 1967, 387 F.2d 102.

Thus the power of the federal district court to entertain the claims of appellees in this case stands on two separate legs of diversity jurisdiction: a claim by an alien against a State citizen; and an action between citizens of different States. We also note, however, the propriety of having the federal district court entertain a spouse’s action against a defendant, where the district court already has jurisdiction over a claim, arising from the same transaction, by the other spouse against the same defendant. See ALI Study of the Division of Jurisdiction Between State and Federal Courts, pt. I, at 9-10. (Official Draft 1965.) In the case before us, such a result is particularly desirable. The claims of Mr. and Mrs. Mas arise from the same operative facts, and there was almost complete interdependence between their claims with respect to the proof required and the issues raised at trial. Thus, since the district court had jurisdiction of Mr. Mas’s action, sound judicial administration militates strongly in favor of federal jurisdiction of Mrs. Mas’s claim.

Affirmed.

7.3.2.2 Sheehan v. Gustafson 7.3.2.2 Sheehan v. Gustafson

John D. SHEEHAN, Sr., Appellant, v. Deil O. GUSTAFSON, Appellee.

No. 91-3078.

United States Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit.

Submitted May 15, 1992.

Decided June 23, 1992.

*1215Timothy D. Kelly, Minneapolis, Minn., argued, for appellant.

Alan L. Kildow, Bloomington, Minn., argued, for appellee.

Before ARNOLD, Chief Judge, LAY, Senior Circuit Judge, and BOWMAN, Circuit Judge.

John D. Sheehan, Sr., appeals the order of the District Court1 dismissing his action for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. We affirm.

Sheehan, a Nevada citizen, commenced an action in February 1991 against Deil 0. Gustafson alleging breach of an oral contract involving the proceeds of the sale of the Tropicana Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada. Sheehan brought his action in federal court in Minnesota, asserting that diversity jurisdiction was proper under 28 U.S.C. § 1332(a) (1988), because Gustaf-son, according to the complaint, was a citizen of Minnesota. Gustafson moved to dismiss the complaint for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. The District Court granted that motion in July 1991, holding that Gustafson, like Sheehan, was a citizen of Nevada and thus there was no diversity of the parties. Sheehan appeals.

A district court’s conclusion as to citizenship for purposes of federal diversity jurisdiction is a mixed question of law and fact (albeit primarily fact). Blakemore v. Missouri Pac. R.R., 789 F.2d 616, 618 (8th Cir.1986). The findings of fact upon which the legal conclusion of citizenship is based thus are subject to review by this Court under the clearly erroneous standard. Id.

The statute conferring diversity jurisdiction in federal court requires that the parties be citizens of different states. 28 U.S.C. § 1332(a)(1). Section 1332(a) must be strictly construed, in view “of the constitutional limitations upon the judicial power of the federal courts, and of the Judiciary Acts in defining the authority of the federal courts when they sit, in effect, as state courts.” Indianapolis v. Chase Nat’l Bank, 314 U.S. 63, 76, 62 S.Ct. 15, 20, 86 L.Ed. 47 (1941) (footnote omitted); accord Owen Equip. & Erection Co. v. Kroger, 437 U.S. 365, 377, 98 S.Ct. 2396, 2404, 57 L.Ed.2d 274 (1978). Thus the burden falls upon the party seeking the federal forum, if challenged, to demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that the parties are citizens of different states. Blake-more, 789 F.2d at 618. The District Court found facts that are not clearly erroneous and determined that Sheehan failed to carry his burden. We cannot say the court erred as a matter of law.

Courts look to the facts as of the date an action is filed to determine whether or not diversity of citizenship exists between the parties. Yeldell v. Tutt, 913 F.2d 533, 537 (8th Cir.1990). “For purposes of diversity jurisdiction, the terms ‘domicile’ and ‘citizenship’ are synonymous.” Id. Therefore, to determine if Gustafson is a citizen of a state other than Nevada, the proper analysis is the two-part test for domicile: Gustafson’s presence in the purported state of domicile and his intention to remain there indefinitely. See id.

The facts of this case, as found by the District Court, indicate that in February 1991 Gustafson had a presence in both Nevada and Minnesota (as well as California and Florida). Gustafson was a citizen of Minnesota until 1973 when he moved to Las Vegas, Nevada, to manage the Tropicana Hotel, which he had purchased in 1972. In 1975, he sold eighty percent of his interest in the hotel. In 1983, Gustafson was convicted in federal court in Minnesota of misappropriation of bank funds and was incarcerated from 1984 to 1987.

The facts found by the District Court that are evidence of Minnesota domicile as *1216of February 1991 include Gustafson’s bank and investment accounts in the state; ownership of property in Minnesota by a corporation controlled by Gustafson, including a condominium whose address Gustafson uses as his own in his monthly reports to his probation officer; Gustafson’s use of corporate vehicles when in the state; location of Gustafson’s secretary and office in Minneapolis, where he regularly checks for messages and mail; location of Gustafson’s physician, dentist, and attorney in the state; and his use of Minnesota addresses and bank accounts for some of his Nevada businesses.

The facts found supporting Nevada domicile include Gustafson’s holding a Nevada driver’s license since 1973 and the registration of his personal vehicles in the state; Gustafson’s filing of Minnesota tax returns as a non-resident since 1974, with a Nevada permanent address shown; Gustafson’s voter registration in Nevada since 1973; his current valid passport showing a Nevada address; Gustafson’s last will (dated July 2,1989) containing a statement that he is domiciled in Clark County, Nevada; use of his parents’ home address in Boulder, Nevada, as Gustafson’s permanent address since the mid-1980’s; and current (as of 1991) construction of a new home on his ranch in Ely, Nevada.2

The facts demonstrate Gustafson’s presence and intent to remain in Nevada, that is, domicile in Nevada. Sheehan did not show by a preponderance of the evidence that Gustafson’s domicile was in fact in Minnesota at the time suit was filed. Shee-han’s evidence to show domicile in Minnesota primarily demonstrates Gustafson’s business contacts and occasional presence in the state; the Nevada contacts are more indicative of intent to remain.

Finding no clearly erroneous findings of fact and no error of law, we affirm the decision of the District Court.

7.3.2.3 Belleville Catering Co. v. Champaign Market Place, L.L.C. 7.3.2.3 Belleville Catering Co. v. Champaign Market Place, L.L.C.

BELLEVILLE CATERING CO., et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. CHAMPAIGN MARKET PLACE, L.L.C., Defendant-Appellee.

No. 02-3975.

United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit.

Argued Oct. 22, 2003.

Decided Dec. 1, 2003.

*640Stephen B. Evans (argued), Deeba Sau-ter Herd, St. Louis, MO, for Plaintiffs-Appellants.

Jerome P. Lyke (argued), Flynn, Palmer & Tague, Champaign, IL, for Defendant Appellee.

Before FLAUM, Chief Judge, and EASTERBROOK and WILLIAMS, Circuit Judges.

Once again litigants’ insouciance toward the requirements of federal jurisdiction has caused a waste of time and money. See, e.g., Hart v. Terminex International, 336 F.3d 541 (7th Cir.2003); Meyerson v. Showboat Marina Casino Partnership, 312 F.3d 318 (7th Cir.2002); Meyerson v. Harrah’s East Chicago Casino, 299 F.3d 616 (7th Cir.2002); Indiana Gas Co. v. Home Insurance Co., 141 F.3d 314 (7th Cir.1998); Guaranty National Title Co. v. J.E.G. Associates, 101 F.3d 57 (7th Cir. 1996); Kanzelberger v. Kanzelberger, 782 F.2d 774 (7th Cir.1986).

Invoking the diversity jurisdiction, see 28 U.S.C. § 1332, the complaint alleged that the corporate plaintiff is incorporated in Missouri and has its principal place of business there, and that the five individual plaintiffs (guarantors of the corporate plaintiffs obligations) are citizens of Missouri. It also alleged that the defendant is a “Delaware Limited Liability Company, with its principle [sic] place of business in the State of Illinois.” Defendant agreed with these allegations and filed a counterclaim. The parties agreed that a magistrate judge could preside in lieu of a district judge, see 28 U.S.C. § 636(c), and the magistrate judge accepted these jurisdictional allegations at face value. A jury trial was held, ending in a verdict of $220,000 in defendant’s favor on the counterclaim. Plaintiffs appealed; the jurisdictional statement of their appellate brief tracks the allegations of the complaint. Defendant’s brief asserts that plaintiffs’ jurisdictional summary is “complete and correct.”

It is, however, transparently incomplete and incorrect. Counsel and the magistrate judge assumed that a limited liability company is treated like a corporation and thus is a citizen of its state of organization and its principal place of business. That is not right. Unincorporated enterprises are analogized to partnerships, which take the citizenship of every general and limited partner. See Carden v. Arkoma Associates, 494 U.S. 185, 110 S.Ct. 1015, 108 L.Ed.2d 157 (1990). In common with other courts of appeals, we have held that limited liability companies are citizens of every state of which any member is a citizen. See Cosgrove v. Bartolotta, 150 F.3d 729 (7th Cir.1998). So who are Champaign Market Place LLC’s members, and of what states are they citizens? Our effort to explore jurisdiction before oral argument led to an unexpected discovery: Belleville Catering, the corporate plaintiff, appeared to be incorporated in Illinois rather than Missouri!

At oral argument we directed the parties to file supplemental memoranda addressing jurisdictional details. Plaintiffs’ response concedes that Belleville Catering is (and always has been) incorporated in Illinois. Counsel tells us that, because the lease between Belleville Catering and Champaign Market Place refers to Belleville Catering as “a Missouri corporation,” he assumed that it must be one. That confesses a violation of Fed. *641R.Civ.P. 11. People do not draft leases with the requirements of § 1332 in mind — perhaps the lease meant only that Belleville Catering did business in Missouri — and counsel must secure jurisdictional details from original sources before making formal allegations. That would have been easy to do; the client’s files doubtless contain the certificate of incorporation. Or counsel could have done what the court did: use the Internet. Both Illinois and Missouri make databases of incorporations readily available. Counsel for the defendant should have done the same, instead of agreeing with the complaint’s unfounded allegation.

Both sides also must share the blame for assuming that a limited liability company is treated like a corporation. In the memorandum filed after oral argument, counsel for Champaign Market Place relate that several of its members are citizens of Illinois. Citizens of Illinois thus are on both sides of the suit, which therefore cannot proceed under § 1332. Moreover, for all we can tell, other members are citizens of Missouri. Champaign Market Place says that one of its members is another limited liability company that “is asserting confidentiality for the members of the L.L.C.” It is not possible to litigate under the diversity jurisdiction with details kept confidential from the judiciary. So federal jurisdiction has not been established. The complaint should not have been filed in federal court (for Belleville Catering had to know its own state of incorporation), the answer should have pointed out a problem (for Champaign Market Place’s lawyers had to ascertain the legal status of limited liability companies), and the magistrate judge should have checked all of this independently (for inquiring whether the court has jurisdiction is a federal judge’s first duty in every case).

Failure to perform these tasks has the potential, realized here, to waste time (including that of the put-upon jurors) and run up legal fees. Usually parties accept the inevitable and proceed to state court once the problem becomes apparent. Perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of this proceeding, however, is the following passage in defendant’s post-argument memorandum:

Defendant-Appellee, Champaign Market Place L.L.C., prays that this Court in the exercise of its Appellate jurisdiction decide the case on the merits and affirm the judgment entered on the jury’s verdict. Surely in the past this Court has decided a case on the merits where an examination of the issue would have shown a lack of subject matter jurisdiction in the District Court. It would be unfortunate in the extreme for Cham-paign Market Place L.L.C. to lose a judgment where Belleville Catering Company, Inc. misrepresented (albeit unintentionally) its State of incorporation in its Complaint.... [Tjhere was no reason for Champaign Market Place L.L.C. to question diversity of citizenship, since it is not, and never has been, a citizen of Missouri.

This passage — and there is more in the same vein — leaves us agog. Just where do appellate courts acquire authority to decide on the merits a case over which there is no federal jurisdiction? The proposition that the Seventh Circuit has done so in the past — a proposition unsupported by any citation — accuses the court of dereliction combined with usurpation. “A court lacks discretion to consider the merits of a case over which it is without jurisdiction”. Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. v. Risjord, 449 U.S. 368, 379, 101 S.Ct. 669, 66 L.Ed.2d 571 (1981). And while counsel feel free to accuse the judges of ultra vires conduct, and to invite some more of it, they exculpate themselves. Lawyers for *642defendants, as well as plaintiffs, must investigate rather than assume jurisdiction; to do this, they first must learn the legal rules that determine whose citizenship matters (as defendant’s lawyers failed to do). And no entity that claims confidentiality for its members’ identities and citi-zenships is well situated to assert that it could believe, in good faith, that complete diversity has been established.

One more subject before we conclude. The costs of a doomed foray into federal court should fall on the lawyers who failed to do their homework, not on the hapless clients. Although we lack jurisdiction to resolve the merits, we have ample authority to govern the practice of counsel in the litigation. See, e.g., Willy v. Coastal Corp., 503 U.S. 131, 112 S.Ct. 1076, 117 L.Ed.2d 280 (1992); Cooter & Gell v. Hartmarx Corp., 496 U.S. 384, 393-98, 110 S.Ct. 2447, 110 L.Ed.2d 359 (1990); Szabo Food Service, Inc. v. Canteen Corp., 823 F.2d 1073 (7th Cir.1987). The best way for counsel to make the litigants whole is to perform, without additional fees, any further services that are necessary to bring this suit to a conclusion in state court, or via settlement. That way the clients will pay just once for the litigation. This is intended not as a sanction, but simply to ensure that clients need not pay for lawyers’ time that has been wasted for reasons beyond the clients’ control.

The judgment of the district court is vacated, and the proceeding is remanded with instructions to dismiss the complaint for want of subject-matter jurisdiction.

7.3.2.4 Notes on Diversity of the Parties 7.3.2.4 Notes on Diversity of the Parties

1. Complete versus Minimal Diversity. Strawbridge v. Curtiss, 7 U.S. (3 Cranch) 267 (1806) announced a rule of complete diversity. At the time, it was unclear whether the rule was based on the Constitution or on the predecessor statute to Section 1332. It is now clear that the case is to be read as one of statutory interpretation, with the Constitution only requiring minimal diversity. See State Farm v. Tashire, 386 U.S. 523 (1967). You might ask: what is complete diversity and what is minimal diversity? Complete diversity requires that no defendant be from the same state as any plaintiff. For example, NY & NJ v. PA & DE satisfies complete diversity; NY & NJ v. PA & NJ does not. Minimal diversity merely requires that some defendant be from a different state from some plaintiff. NY & NJ v. NJ does satisfy minimal diversity. Later on in the course we will discuss a part of Section 1332 we are skipping over now, the Class Action Fairness Act. This statute allows certain types of class actions to be brought in federal court where there is only minimal diversity. For ordinary § 1332(a) diversity claims, however, full diversity is required.

2. Determining Domicile Generally. The test for creating a new domicile for individuals has two elements: 1) residence in a state with 2) intent to remain 'indefinitely.' Indefinitely does not include an uncertain period of time but with a departure expected (for example, 'until I finish my degree'); it means an intent to remain perhaps permanently. Once fixed, it takes more than a change of residence to reset domicile. There must be an intention to stay indefinitely. Without that intent, domicile remains where it has been. What would have happened in Mas if the plaintiff had decided at any point while she was resident in Louisiana that she wanted to make Louisiana her permanent home? What would her domicile be if after the facts in this case she moved to, say, Ohio, but did not form an intent to remain indefinitely?

3. Determining Domicile for Corporations and Unincorporated Entities. As Judge Easterbrook reminds us, the test for determining domicile depends on the nature of the party. Individuals are treated differently from corporations, which are treated differently from partnerships, LLCs, and other unincorporated associations such as labor unions. For unincorporated associations, we look to the residence of each partner or member. As a practical matter, for some organizations such as national labor unions this makes bringing a diversity claim essentially impossible as there are likely to be members in every state. For corporations, the rule makes clear that there are possibly two domiciles, very similar to what we saw in Daimler - the state of incorporation and the principal place of business. In Hertz Corp. v. Friend, 559 U.S. 77 (2010), the Court made clear that the principal place of business is not where a corporation conducts the most business or makes the most sales, but where its 'nerve center' is. As a practical matter, in almost every case the nerve center will be the location of the corporate headquarters.

4. Note on LLCs: You might not have covered Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) in Business Associations, which often focuses on corporations and partnerships. LLCs are a relatively recent innovation in company structure, having originated in the latter part of the 20th century in the US. They combine some aspects of partnerships that are often attractive to investors (such as tax pass-throughs so losses are deductible by investors) and aspects of corporations that are attractive as well (such as limited liability). They have become a very popular structure for smaller, privately held companies. Beyond LLCs, partnerships, and corporations, note that the variety of business organizations in the US can be bewildering. It is important to pay close attention to what the structure is. The situation gets more complicated, and beyond the scope of this course, when foreign business entities are involved. China has LLCs, for example. What would be the domicile of a Chinese LLC that has US domiciliaries and Chinese domiciliaries as members? So far as we know, no case to date has confronted that.

5. Time for determining domicile of parties. People and companies, including parties and potential parties to litigation, sometimes move. At what time do we assess domicile? At the time the action arose? At the time the lawsuit was filed? At the time the court is deciding the issue? The answer is simple - at the time the lawsuit is filed. Subsequent moves will not divest the court of jurisdiction. Moves that take place before filing, even if they have the effect of either creating or denying diversity, will not normally be questioned so long as the move is a real move in good faith and not a pretense. What would be the analysis if Mas had moved to Ohio, permanently and with an intention to stay, before filing suit? What would the analysis be if after the facts giving rise to the lawsuit but before filing she had decided to remain in Louisiana indefinitely?

6. Pleading Domicile. The party asserting a claim must plead those facts essential to establish subject matter jurisdiction. Because courts are not free to hear cases that fall outside the limited subject matter reach of the federal courts, this is not something federal judges will ignore. A litigant who makes conclusory or unclear allegations of subject matter jurisdiction may - and probably will - be allowed an opportunity to amend the complaint to make the allegations sufficient, but if the litigant fails to get the job done the case will be dismissed. This will happen even if the true, but unalleged facts, would support a finding of subject matter jurisdiction if the court knew about them. See Sienna Ventures, LLC v. Halley Equipment Leasing, LLC, 2018 WL 3153475 (E.D.N.Y Apr. 2, 2018) (Dismissing for lack of subject matter jurisdiction where after three tries plaintiff's jurisdictional allegations of “subject matter jurisdiction exists in this case" were not enough even though Sienna Ventures, LLC is a New York Limited Liability Company and its sole member is a citizen and resident of New York, and Halley Equipment Leasing, LLC is a Texas Limited Liability Company.” The complaint failed to state the domiciles of all the LLC members, which if they had been alleged would have satisfied subject matter jurisdiction).

7. Proving Domicile. As both Mas and Sheehan v. Gustafson note, establishing domicile depends on a two part test - presence in a state and intent to remain. But how do we determine domicile when it is disputed? Do we just take a party's word at face value? Sheehan v. Gustafson makes several things clear. First, it is the burden of the claimant to establish subject matter jurisdiction. Second, we do not simply accept assertions at face value, but look to evidence such as where one votes or has a driver's license to inform the assessment. Third, while the burden is on the claimant, if the issue is disputed the court will normally allow discovery in order to establish the facts (with the costs and process of discovery something that should be taken into account before domicile is challenged). Finally, the determination is one within the discretion of the trial court, and reviewing courts will apply an abuse of discretion standard when reviewing the determination of the trial court. In some cases, and Sheehan v. Gustafson is an excellent example, determining residence can be far from straightforward. You will note from Sheehan v. Gustafson that a number of documents can be used to show domicile, from passports to driver's licenses to voter registrations, and they may not be consistent. Compare that to China, where official residency is determined by a hukou document, with important consequences that flow from the official documentation.

8. U.S. Citizens Domiciled in No State: Can diversity or alienage jurisdiction be asserted over someone who is a U.S. citizen but not domiciled in any state in the U.S.? In the age of globalization, this has become not uncommon, as U.S. citizens establish residency in foreign countries and for tax or other reasons have no connection with any single US state. Are they citizens of a state? Are they subjects or citizens of a foreign country? If you think about it, you will see that they are neither - still US citizens but not resident in any state. Note what the court in Mas said when it considered what would be the impact of imputing her husband's residency to her: "She would not be a citizen of any State and could not sue in a federal court on that basis; nor could she invoke the alienage jurisdiction to bring her claim in federal court, since she is not an alien."

9. Citizenship of Wife. Mas v. Perry discusses a rule where for US citizens the domicile of the wife was set conclusively as that of the husband. Like many other legal rules from earlier eras that assumed that wives were subordinate to husbands, that rule no longer applies. The established domicile of a spouse, either spouse, might be probative as a factual matter in a close factual case, but today there will be no conclusions reached based solely on the domicile of the husband.

10. Why Diversity? Diversity jurisdiction has long been controversial. After all, in every case a state court could also resolve the dispute, and there are those who argue (mostly not experienced trial lawyers) that prejudice against out of state parties is a thing of the past. Maintaining diversity access has many costs. First, it complicates things procedurally. As you should have noticed over and over again in the progression of this course, battling over forum selection is something lawyers spend a lot of time engaged in, and diversity jurisdiction creates opportunities for extensive procedural battles related to such issues. It also imposes significant burdens on the federal courts. In 2019, of 286,289 total cases filed in district court that year 94,206 - or nearly 33 percent - were diversity cases. Arguments are also made that diversity cases are more time consuming than the average case, and more likely to go trial. Diversity cases also shift resolution of state law issues to the federal courts, whereas without diversity at least some of these state legal issues would be resolved within the state system whose law is involved. On the other hand, diversity jurisdiction allows national procedural tools such as multidistrict litigation to be employed on mass tort or other aggregate cases. Many lawyers and parties also passionately believe that the days of local prejudice against outsiders are not an artifact of history but remain a live concern. Then, there are those who appreciate and value the forum selection potential - they might prefer a federal jury venire, which tends to draw from a wider area than a state jury pool, or they may prefer federal judges, who tend to be highly capable. In any event, diversity jurisdiction abides, and you should not expect it to quickly or easily go away.

7.3.2.5. US Federal Court Cases By Type

7.3.2.6 Problems and Hypotheticals 7.3.2.6 Problems and Hypotheticals

See if you can work through the following problems. Answers will eventually be provided, but you will be much better prepared for the exam (and life as a lawyer who must resolve such issues with no one giving you the answer) if you make the effort to solve problems like this on your own.

Judy Moore was born and raised in the university town of Oxford, Mississippi, where both her parents were professors. At age 18 she enrolled in college in Wellesley, Massachusetts, and after graduation with a degree in economics began a graduate program in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Early on during her ten years in Massachusetts she learned that she didn't like snow, and hoped that when she graduated she could secure a teaching job in a warmer climate. Near the end of her doctoral studies, she traveled for a job interview to Athens, Georgia, where she was offered and quickly accepted a job as a university professor. She liked Athens, and hoped she could spend the rest of her life there. While in Athens, unfortunately, she was injured when a car owned by LaGlace Enterprises struck her. The car was driven by Justah Dope, a student at the University of Georgia. Dope was originally from Chattanooga, Tennessee, and planned to move to New York, New York, to pursue a career as an actor upon graduation, but he has little likelihood of actually securing a job offer there and may be forced to remain in Georgia indefinitely. LaGlace Enterprises is a limited liability company created under the laws of Mississippi and headquartered in Columbia, South Carolina. The members (owners) are Perry Miroir, a resident of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and Edgar Espejo, a resident of Athens, Georgia. Once back in Massachusetts, Moore consulted with a lawyer, who advised her to bring a lawsuit. The lawsuit was filed in federal district court in Georgia shortly before Moore obtained her PH.D. degree against Dope and LaGlace Enterprises. Shortly after the lawsuit was filed but before the judge could hear a motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, Moore moved to Georgia to start her new job. With regard only to the diversity of the parties, please analyze the issues.

MuchoDinero, LLC, is a limited liability company created under the laws of Nevada and headquartered in Tucson, Arizona. It has members (owners) from Arizona, California, and Utah. LotsaMonie, LLC, is a limited liability company created under the laws of Washington state and headquartered in Portland, Oregon. It has members from Oregon, Washington state, and Idaho. MuchoDinero filed a suit against LotsaMonie in federal district court in Portland. The complaint alleged “subject matter jurisdiction exists in this case as MuchoDinero is a Nevada Limited Liability Company and LotsaMonie is a Washington state Limited Liability Company.” After giving MuchoDinero repeated opportunities to amend its complaint, the judge dismissed the lawsuit for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. Did the judge act properly?

7.3.3 Alienage Jurisdiction 7.3.3 Alienage Jurisdiction

7.3.3.1 Hebei Tiankai Wood & Land Constr. Ltd. v. Chen, 348 F Supp 3d 198 (EDNY 2018). 7.3.3.1 Hebei Tiankai Wood & Land Constr. Ltd. v. Chen, 348 F Supp 3d 198 (EDNY 2018).

MEMORANDUM & ORDER

JACK B. WEINSTEIN, Senior United States District Judge:

Table of Contents

I. Introduction...200

II. Facts...200

A. Transaction...200

B. Dispute...201

C. Motion to Realign and Dismiss...202

III. Law...202

A. Summary Judgment Standard of Review...202

B. Diversity Jurisdiction...203

C. Antagonism Doctrine...203

IV. Application of Law to Facts...204

A. Plaintiff's Showing of Antagonism...204

B. Importance of Alienage Jurisdiction...204

V. Conclusion...206

I. Introduction

This litigation arises from a transnational business transaction gone wrong. In 2017, Hebei Tiankai Wood & Land Construction Co. Ltd. (“Plaintiff”) and Kirin Transportation, Inc. (“Kirin”) agreed that Plaintiff would become majority shareholder of Kirin. At the time of the transaction, Frank Chen (“Chen”) was the sole owner of Kirin. Plaintiff alleges that Chen made false representations to induce Plaintiff to invest $300,000 in Kirin and then misused the money.

Chen moved to dismiss under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(1) for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. The court ordered the motion converted to one for summary judgement.

Plaintiff is a citizen of China, while Chen and Kirin, the nominal defendant, are citizens of New York. Chen argues that Plaintiff's fraudulent inducement and breach of fiduciary duty claims are derivative, properly belonging to Kirin, so Kirin should be aligned as a plaintiff. Realignment of Kirin as plaintiff would destroy diversity, requiring the case to be dismissed.

Plaintiff argues that the “doctrine of antagonism”—applicable between Kirin and Plaintiff—applies, so that realignment is not required.

Chen disagrees. He contends that Plaintiff is Kirin's majority shareholder so that there is no antagonism between these two.

Chen's argument is not persuasive. First, even if Plaintiff has de jure control of Kirin, Chen has de facto control. Chen is alleged to have forcefully rebuffed Plaintiff's attempts to take control of Kirin, even though Plaintiff is now majority shareholder of Kirin. The caselaw is clear that a court should ensure that the parties are aligned so that there is a real collision of interests.

The real collision of interests is between Plaintiff on one side and Chen and Kirin on the other. Second, at its core, this is a dispute between nationals of the United States and of China, making it desirable to try the case in federal court if subject matter jurisdiction exists.

Kirin should remain as a named defendant. This court has jurisdiction over Plaintiff's claims. Chen's motion is denied.

II. Facts

A. Transaction

Plaintiff is a construction company based in China. Compl. ¶ 4, ECF No. 1, *201 May 10, 2018; Answer Ex. C, ECF No. 9-3. Chinese nationals Qiuxiang Shi (“Shi”) and Yingjie Li (“Li”) are the sole owners, officers, and managers of Plaintiff. Compl. ¶¶ 8, 17. In November 2017, Shi and Li traveled to New York and were introduced to Chen, then the sole shareholder of Kirin. Id. ¶¶ 9–11; Answer ¶¶ 9–11, ECF No. 9, May 29, 2018. Chen is a resident of the State of New York; Kirin is a New York corporation. Compl. ¶¶ 5–6; Answer ¶¶ 5–6. Kirin is alleged to be only a nominal defendant. Compl. ¶ 6.

Chen invited Shi and Li to Kirin's headquarters in Queens, New York. Id. ¶ 12; Answer ¶ 12. He wanted the duo to invest in Kirin. Id. Plaintiff alleges that Chen represented that Kirin was a successful company looking to expand its business; he gave Shi and Li documents to “highlight the financial strength” of the company. Compl. ¶¶ 13–14. It is undisputed that Chen stated that if Shi and Li invested in Kirin, Kirin would sponsor Shi for an L-1 visa. Id. ¶ 18; Answer ¶ 18. Plaintiff alleges that the visa would have allowed Shi to travel to the United States to participate in the management of Kirin and monitor operations of the company. Compl. ¶ 18. Chen organized meetings with law firms specializing in immigration law to demonstrate his intent to help obtain the visa if Plaintiff invested in Kirin. Id. ¶ 19; Answer ¶ 19.

The parties agree that Chen offered Shi and Li 51% of the shares of Kirin for $300,000 in capital investment. Compl. ¶ 20; Answer ¶ 20. Plaintiff alleges that Chen also promised to pay Shi a substantial salary as a manager. Compl. ¶ 20. On November 28, 2017, Chen gave Shi and Li a contract memorializing the agreement; in exchange for $300,000, Kirin agreed to tender 51% of Kirin's shares to Plaintiff and to file an L-1 visa petition for Shi. Id. ¶¶ 20, 22; Answer Ex. E, ¶¶ 1–2, ECF No. 9-5. Chen signed an engagement letter with a lawyer to work with Kirin to obtain the visa. Compl. ¶ 26; Answer ¶ 26. On the same day, Plaintiff tendered a certified check to Kirin for $300,000. Compl. ¶ 28; Answer ¶ 28. A stock certificate in turn issued to Plaintiff was for 102 shares, a majority of those in the company. See Decl. Frank Chen Ex. B, ECF No. 18-4.

B. Dispute

What had seemed like a straightforward transaction then began to unravel. In January 2018, per Plaintiff's allegations, Chen contacted Shi and Li asking for additional funds to be invested in Kirin so that Kirin could help obtain a visa for Shi. Compl. ¶ 30. Allegedly, Chen represented that the funds already invested “had been used up.” Id. ¶ 31. Plaintiff became suspicious and asked Kirin for documents and records, which Chen refused to produce. Id. ¶ 32. The parties agree that in April 2018, Plaintiff discovered that it was not listed as a shareholder on Kirin's 2017 tax returns. Id. ¶ 35; Answer ¶ 35.

Plaintiff attempted to establish control of Kirin. Plaintiff alleges that it sent a representative to take over Kirin, but its employees (pursuant to Chen's instructions), refused the representative access to the premises and inspection of books and records. Compl. ¶ 33. Alleged is that Kirin's bank refused to make account records available, and that Chen had never told Kirin's employees of Plaintiff's investment, never informed the landlord of the property where Kirin operated of Plaintiff's investment, and never made Plaintiff an authorized signatory on any of Kirin's bank accounts. Id. ¶¶ 33–34.

Chen denies these allegations. Answer ¶¶ 33–34. But, based on the record, they appear to be true. See Hr'g Tr. 4:15–19, *202 5:1–3, Dec. 19, 2018 (parties agree no evidentiary hearing was required).

In April 2018, Shi, as chair and director of Kirin, removed Chen from all positions at Kirin and named Shi chief executive officer of Kirin. Decl. Frank Chen Ex. D, ECF No. 18-5. Shi also named an interim chief executive officer of Kirin, effective immediately. Decl. Frank Chen Ex. D, ECF No. 18-6.

Chen took steps to counter these moves. On April 17, 2018, his attorney Xiangan Gong (“Gong”) wrote to Plaintiff's counsel opposing the “attempted take-over of the business.” Decl. Jacob Chen Opp. Frank Chen’s Mot. Dismiss Ex. A, ECF No. 23-2 (“Pl. Ex. B”). Gong wrote:

The stock transfer agreement between the parties entered last November was never finalized: (1) Frank Chen was and still is the one who actually supervises and manages the company's daily business operation, Qiuxiang Shi had never participated into company's management or business operation; (2) the lease was signed by Frank Chen; (3) Frank Chen was the only authorized personnel for the company's bank account.

Id. (emphasis added). In the same email, Gong wrote, “[Chen] CANNOT LEAVE THE COMPANY AND LET YOUR CLIENT OPERATE THE BUSINESS WITH HIS LEASE, SUBJECT HIM TO VIOLATION OF THE LEASE.” Id. (capitalization in original).

On May 1, 2018, Gong repeated Chen's position that he properly maintained control of Kirin. Decl. Jacob Chen Opp. Frank Chen’s Mot. Dismiss Ex. B, ECF No. 23-3 (“Pl. Ex. B”). Gong wrote,

[Chen] prefers to do a clean-cut closing then your client takes full control of the corporation and its business operation.... [Chen] cannot gives [sic] up the management right when the lease agreement and most importantly the company's TLC license was under his name.

Id.

C. Motion to Realign and Dismiss

In May, Plaintiff brought three causes of action against Chen and Kirin: (1) fraudulent inducement; (2) breach of contract; and (3) breach of fiduciary duty. Compl. at 6–9. Alleged is that a demand for Kirin to institute suit against Chen would be futile. Id. ¶ 7. Chen and Kirin filed a joint answer in response to Plaintiff's complaint. Answer at 1. By August, Chen had hired new counsel for himself, but he declined to hire new counsel for Kirin. Minute Entry, ECF No. 25, Aug. 15, 2018.

Chen's new attorney filed a motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, arguing that Kirin should be realigned as a plaintiff, thus destroying the complete diversity of citizenship required for this court to have subject matter jurisdiction. See Def. Chen's Notice Mot. & Mot. to Dismiss Under Rule 12(b)(1) for Lack of Subject Matter Jurisdiction at 4, ECF No. 18, Aug. 5, 2018.

This court converted Chen's motion to dismiss to a motion for summary judgment. Order, ECF No. 26, Aug. 27, 2018. A hearing on the motion was held on December 19, 2018. See Hr'g Tr., Dec. 19, 2018. The parties agreed that the motion could be decided without an evidentiary hearing. Id. 4:15–19, 5:1–3.

III. Law

A. Summary Judgment Standard of Review

12At the summary judgment stage, “the judge's function is not ... to weigh the evidence and determine the truth of the matter but to determine whether there is a genuine issue for trial.” *203 Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 249, 106 S.Ct. 2505, 91 L.Ed.2d 202 (1986). The movant must show that “there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(a). A genuine dispute of material fact exists for summary judgment purposes when, “the evidence, viewed in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, is such that a reasonable jury could decide in that party's favor.” Chaohui Tang v. Wing Keung Enterprises, Inc., 210 F.Supp.3d 376, 388 (E.D.N.Y. 2016) (quotation marks and citation omitted).

B. Diversity Jurisdiction

3District courts have original jurisdiction of civil actions between a citizen of one state and a citizen of a foreign state when the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000. 28 U.S.C. § 1332(a). Alienage jurisdiction is a subset of diversity jurisdiction.

456“[D]iversity jurisdiction is available only when all adverse parties to a litigation are completely diverse in their citizenships.” Herrick Co. v. SCS Communications, Inc., 251 F.3d 315, 321 (2d Cir. 2001). Federal diversity jurisdiction cannot be conferred by the parties' own determination of who should be plaintiffs and who should be defendants. Rather, “the federal courts are required to realign parties according to their real interests so as to produce an actual collision of interests.” Lewis v. Odell, 503 F.2d 445, 447 (2d Cir. 1974); see also City of Indianapolis v. Chase Nat. Bank of City of New York, 314 U.S. 63, 69, 62 S.Ct. 15, 86 L.Ed. 47 (1941) (it is the court's duty to “look beyond the pleadings, and arrange the parties according to their sides in the dispute” (citation omitted)).

C. Antagonism Doctrine

78Generally, a shareholder has no individual cause of action for a wrong against a corporation. Abrams v. Donati, 66 N.Y.2d 951, 498 N.Y.S.2d 782, 489 N.E.2d 751, 751 (N.Y. 1985). This results in the corporation being aligned as the plaintiff in litigation brought to remedy harm to a corporation because the corporation is the real party in interest. See Liddy v. Urbanek, 707 F.2d 1222, 1224 (11th Cir. 1983).

91011When, however, “management is aligned against the stockholder and defends a course of conduct which [the stockholder] attacks,” there is “antagonism” and the corporation should be aligned as a defendant. Smith v. Sperling, 354 U.S. 91, 95, 77 S.Ct. 1112, 1 L.Ed.2d 1205 (1957). Fraud, breach of trust, and illegality on behalf of the management in control are strong indicators of antagonism. Id. (collecting cases); ZB Holdings, Inc. v. White, 144 F.R.D. 42, 46 (S.D.N.Y. 1992) (“[I]f the complaint in a derivative action alleges that the controlling shareholders or dominant officials of the corporation are guilty of fraud or malfeasance, then antagonism exists, and the corporation should be aligned as a defendant.”). Antagonism may also exist where management is hostile to the interests of shareholders. Smith, 354 U.S. at 97, 77 S.Ct. 1112; Rogers v. Valentine, 426 F.2d 1361, 1363 (2d Cir. 1970) (upholding the district court's decision that a corporation should be aligned as a defendant when management had refused to institute suit on behalf of the corporation and demand would be futile).

12Courts should normally determine the issue of antagonism without delving into the merits of the claims. See Smith, 354 U.S. at 95, 77 S.Ct. 1112 (“the instant case is a good illustration” of why not “to delve into the merits” “for it has been over *204 eight years in the courts on this question of jurisdiction”).

IV. Application of Law to Facts

A. Plaintiff's Showing of Antagonism

13It is assumed for purposes of this opinion that Plaintiff's claims are derivative and intended to remedy wrongs to the corporation. Nevertheless, Kirin remains properly aligned as a defendant because of antagonism.

First, though Plaintiff has de jure control of Kirin, Chen has de facto control. It is undisputed that Chen is managing Kirin and Plaintiff's attempts to obtain control have failed. Those attempts are alleged to have been forcefully rebuffed by Chen. At his direction, Kirin's employees denied Plaintiff access to Kirin's operating premises and books and records. Chen also denied Plaintiff access to Kirin's bank by failing to make Plaintiff a signatory on Kirin's bank account.

Chen has explicitly refused to cede control of Kirin to Plaintiff. In April 2018, Shi, chair and sole director of the corporation, “removed” Chen from all positions in Kirin and appointed a new chief executive officer of Kirin. But Chen refused to cede management of Kirin to Shi's appointee. See Pl. Ex. A (“Mr. Chen DOES oppose the attempted take-over of the business.” (emphasis in original) ); id. (“Frank Chen was and still is the one who actually supervises and manages the company's daily business operation”); Pl. Ex. B (“[Chen] cannot gives [sic] up the management right”).

In view of Chen's actual management of Kirin and Plaintiff's alleged inability to wrest control from him despite being majority shareholder, it is highly unlikely that Chen would institute either of Plaintiff's derivative claims against Kirin. Based on the facts alleged in the complaint, such a demand would be futile. In these circumstances, antagonism exists. See Rogers, 426 F.2d at 1363 (upholding the district court's decision that a corporation should be aligned as a defendant when management had refused to institute suit on behalf of the corporation and demand would be futile).

14Second, Plaintiff alleges that Chen has engaged in fraud by wasting the investment in Kirin by Plaintiff and by engaging in other acts of malfeasance, including failing to list Plaintiff as a shareholder on Kirin's 2017 tax returns. When the dominant official of the corporation is accused of fraud, the corporation is appropriately aligned as a defendant. See ZB Holdings, 144 F.R.D. at 46 (concluding that “the requisite antagonism” existed because plaintiff alleged that the corporation's directors—the “dominant officials”—had engaged in common law fraud and misrepresentation).

Chen argues that antagonism cannot be found because Plaintiff is the majority shareholder of Kirin. Majority “control” of a corporation, however, is only one “circumstance indicating a lack of antagonism.” Taylor v. Swirnow, 80 F.R.D. 79, 83 (D. Md. 1978) (concluding that the parties lacked antagonism when plaintiffs owned a majority share in the corporation, among other reasons).

The court's role is to determine where the real collision of interests lies. The pleadings show that collision between Plaintiff on one side and Chen and Kirin on the other.

B. Importance of Alienage Jurisdiction

This litigation, at its core, is a transnational business dispute between a Chinese corporation and a New York citizen. It is the transnational nature of the action—and the fact that all relevant activity took place *205 in the United States—that make it vital that the parties be able to litigate in a United States court. Reliability of the United States courts is apparent.