11 Joinder 11 Joinder

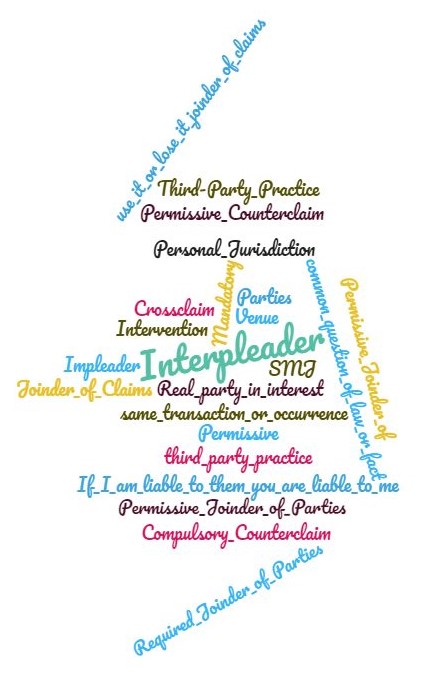

11.1 Joinder Wordcloud 11.1 Joinder Wordcloud

11.2 Joinder in U.S. Federal Court - The Tools 11.2 Joinder in U.S. Federal Court - The Tools

Joinder of Claims. Rule 18(a) allows a party bringing a claim to add to it any claim, related or unrelated, that it might have against the other party. There are no subject matter limitations. Subject matter jurisdiction must be established for the claim, though, and venue and personal jurisdiction when brought by a plaintiff.

Joinder of Parties. The joinder of parties rule is broad, but not as open ended as joinder of claims. Rule 20 provides two tests, both of which must be met. Parties may join as plaintiffs if they assert claims “arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences” and there is “any question of law or fact common to all plaintiffs” that will arise in the action. A nearly identical rule applies to joinder of defendants. If you stop to think through these two tests, it is hard to imagine a party whose potential presence arises from the same set of circumstances that would not be joinable. Note that this rule is permissive, not mandatory, and for a variety of reasons (e.g., preserving subject matter jurisdiction, only presenting defendants with deep pockets to the jury) a plaintiff might decide not to include certain defendants. For similar reasons a plaintiff might or might not choose to proceed with co-plaintiffs.

Development of a Lawsuit: The following charts attempt to give a visual depiction of how a lawsuit might develop and become more complicated at the joinder rules are employed.

P1 and P2 bring claims against D1 and D2. P1’s claims against D1 are unrelated to each other, but the first arises from the same transaction or occurrence as the claims against D2. P2’s claims against D1 and D2 will require resolution of “questions of law or fact” related to P1’s first claim against D1.

P1 D1

P2 D2

D1 and D2 bring counterclaims against P1. D1’s claim is related and hence mandatory, D2s is completely unrelated and hence permissive.

P1 D1

P2 D2

D2 brings cross claims against D1. One arises from the same transaction or occurrence; one does not. D1 counterclaims back against D2 with a claim unrelated to either of D2’s claims.

P1 D1

P2 D2

D2 now impleads 3D, claiming that if he owes money to P2, 3D owes money to him.

P1 D1

P2 D2 3D

It can get vastly more complicated, but that is enough to give you a sense.

Remember that for each claim you must establish subject matter jurisdiction, and will be expected to do so in any exam we give in this course. The applicability of venue and personal jurisdiction become murkier in practice, and we won’t test on that.

Claims by Plaintiff. Rule 18(a) allows the plaintiff to bring “as many claims as it has” against any defendant. As we saw, the Rules do not require that additional claims be brought, but as noted we will see when we get to claim preclusion that the plaintiff effectively must assert or lose every claim that arises from the same circumstances. With regard to defendants, as we saw in the brief discussion of joinder of parties, the plaintiff is not quite so unconstrained, but Rule 20 is broad enough to allow the plaintiff to bring as defendants pretty much any defendant where there is a connection between the claims against that defendant and the other defendants in the case. The plaintiff is not required by either the Rules or any other doctrine to join any defendants so long as they are not the sort required under Rule 19, and as we will see the sort required under Rule 19 is a much smaller group than those who might also be liable. The plaintiff may also file claims against other plaintiffs as a cross claim so long as the initial crossclaim meets the relatedness test in Rule 13. Remember also that the plaintiff can turn into a third party defendant upon assertion of a counterclaim or crossclaims from other plaintiffs, and in that circumstance the rules applying to defendants apply to the plaintiff to the extent she is a defendant. Remember that for all claims the requirements of personal jurisdiction, venue, and subject matter jurisdiction must be met aside from the rules.

Claims by Defendant. The range of claims by a defendant is also quite broad. First, she must assert or lose mandatory counterclaims, and may assert permissive counterclaims. For all claims, subject matter jurisdiction must be established. Venue and personal jurisdiction are generally viewed as waived with regard to claims against the plaintiff, and we won’t in this class look at the exceptional or theoretical case. The defendant may also assert crossclaims against other defendants so long as the first crossclaim asserted meets the relatedness test of Rule 13. Again, subject matter jurisdiction must be met. Cross claims are permissive, not mandatory, although counterclaims to a crossclaim can be mandatory, same as other crossclaims. Defendants can also ‘implead’ third parties that it claims are liable to it if it is liable to the plaintiff. Remember that for each claim there must be a basis for federal subject matter jurisdiction.

Pro Mnemonic Tip. If the joinder device involved begins with a C (such counterclaim or crossclaim) it is between parties already in the case. If it begins with the letter I (such as impleader or intervention) it involves bringing a new party into the case.

Now we will consider the various rules one at a time.

Rule 13. Counterclaim and Crossclaim. Counterclaims come in two varieties – compulsory and permissive. In general, if a claim arises out of the transaction or occurrence that underlies the plaintiff’s claim, it is a compulsory counterclaim. The exceptions are if it is the subject of an action that predated the plaintiff’s claim, if it requires adding a party over whom the court cannot get jurisdiction, or if the original claim was in rem or quasi in rem and the counterclaim would not be. The consequences of a counterclaim being compulsory are simple – if not brought, it cannot be brought in a different action. Permissive counterclaims are all counterclaims that are not mandatory.

Let’s see how this works. Perry Plaintiff sues Don Defendo claiming a breach of contract relating to Plaintiff’s of a million widgets to Defendo. Plaintiff claims that Defendo has only paid part of the purchase price. Defendo has two potential counterclaims. One would assert that the widgets were defective and that not only should Defendo not pay, but that he is entitled to get back the money he did pay plus special damages incurred because he was unable to deliver the widgets to his customers. The other arises from a sale of woodgets two years before, and which has no factual overlap with widget transaction. Whether or not Defendo likes the forum Plaintiff has selected, he must bring the widget counterclaim as a compulsory counterclaim. The other claim he may bring as a permissive counterclaim (and may choose to in order to consolidate his claims against Plaintiff or to increase his settlement leverage) or he can bring it in a separate court at a different time. What happens if Defendo fails to bring the widget claim as a compulsory counterclaim but files it in a different court? It will be dismissed because it should have been brought as a compulsory counterclaim.

Crossclaims are claims between two parties on the same side of the case – for example, between two plaintiffs or between two defendants. The first crossclaim requires a connection to the plaintiff’s claims. It is allowed only “if the claim arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the original action or of a counterclaim, or if the claim relates to any property that is the subject matter of the original action.” Once that claim is filed, however, Rule 18 kicks in and additional unrelated claims can be joined, and the party sued must respond with compulsory counterclaims and may respond with permissive counterclaims.

Rule 14. Third-Party Practice. Students often get confused about impleader. It is important to understand that impleader addresses a particular kind of situation, and does not provide a vehicle for bringing in all kinds of third parties, even if an argument can be made that they are the truly liable party. Look at the rule. It allows a defendant to bring in a defendant who “is or may be liable to it for all or part of the claim against it.” That does not mean “may be liable instead.” We saw an example of impleader in the Asahi case. The plaintiff sued the manufacturer of the motorcycle tire. The manufacturer of the motorcycle tire concluded – without necessarily admitting – that if there was a problem with the motorcycle tire, it was because the valve on the tire failed. The valve manufacturer was then impleaded on the theory that it should pay to the tire manufacturer all or part of the damages the tire manufacturer had to pay to the plaintiff. This was the part of the litigation that was still alive when the Supreme Court addressed the personal jurisdiction issues. Other common applications include guarantors and indemnitors (if I am held liable you promised to make me whole) and insurers. Note that the defendant/third party plaintiff does not have to admit liability to the original plaintiff but can bring in the third party defendant in case liability is established. Note also the key point – it must involve liability by the third party defendant to the original defendant/third party plaintiff related to the original claim.,

So, imagine a case where Perry Plaintiff is suing Don Defendo for an automobile accident in which he claims Defendo veered onto the sidewalk and ran him down. Defendo now wishes to implead Arnie Insurer who has insured Defendo against claims relating to his automobile driving, but has refused to defend this lawsuit. That would be a proper impleader. On the other hand, assume that Defendo wishes to implead Danny Driver, based on a claim that it was Driver, not Defendo, who actually struck Plaintiff. That would not be a proper impleader. Do you see why?

Rule 17. Plaintiff and Defendant; Capacity; Public Officers. Under the common law, actions had to be brought in the name of the party holding the ultimate legal right. Assignees, for example, could not sue in their own names. This led to contortions in pleading, and was abandoned under the pleading codes and also in equity. This rule carries forward the choice by the codes and equity to look not at nominal holders of rights but at the party – such as an assignee – actually affected. The party actually holding the right should be the party in the caption asserting or defending the claim. We won’t spend any more time on this rule.

Rule 18. Joinder of Claims. Rule 18(a) is very straightforward – so far as pleading goes, a plaintiff can bring any claim it has against a defendant. The same applies to those asserting counterclaims or crossclaims (so long as the first crossclaim against a party meets the relatedness test of Rule 13).

Rule 19. Required Joinder of Parties. Rule 19 can be difficult. A rule 19 situation arises when there is a potential party not joined in the lawsuit (Absentee) and someone argues that Absentee really, really needs to be part of the lawsuit. In a typical Rule 19 situation neither the plaintiff (who could have joined anyone who meets the standards of Rule 20, assuming SMJ, PJ, and Venue are met) or Absentee (who could have intervened, assuming SMJ) really want Absentee to be in the lawsuit. Rule 19 first sets out a three-part test. The test is of the either-or type, where meeting the standards of any one of the three parts of the test makes the Absentee a party to be joined if feasible. These tests are whether the party can give full relief without Absentee being joined, whether some interest of Absentee may be impaired if Absentee is not joined, or if failure to join Absentee can lead to multiple or inconsistent obligations (as in, an order from a different court ordering the defendant to do give to Party X an object that the first court might order the Defendant to give to Party Y).

Imagine that Student Z brings a lawsuit to order Evil Professor to deliver to her the Magic Water Bottle of Shenzhen, which Evil Professor took from the desk of Student Absentee and which Absentee is known to claim ownership of. Would Absentee’s interest be impaired if the court orders the bottle delivered to Student Z? Possibly. Might Evil Professor face inconsistent obligations if in a different suit Absentee obtains an order directing the that water bottle be delivered to her? Absolutely.

The first part is the easy part. Now let’s assume that the party to be joined cannot be joined – there is no personal jurisdiction or venue or inclusion of Absentee would destroy subject matter jurisdiction. The question then is whether to dismiss the lawsuit or to proceed without Absentee. The rule sets out a four part test to help the court work through that issue. We will read a case applying that rule so hold tight.

One thing to remember about Rule 19 from the perspective of transnational litigation is that the rule comes into play when a party cannot be joined - either because there is no personal jurisdiction or because adding the party would destroy subject matter jurisdiction. One does not to be as smart as you are to immediately see how those situations could arise in litigation involving overseas defendants.

Rule 20. Permissive Joinder of Parties. As the name of the rule suggests, Rule 20 allows but does not require joinder of parties. The test is two part – same transaction or occurrence plus a common question of law or fact. As noted above, for a number of reasons parties might choose not to join all permissible parties. For example, a defendant who would destroy federal subject matter jurisdiction can be left out. Similarly, a defendant who has no money may not be joined because the plaintiff does not want a verdict returned against a judgment proof defendant. Similar logic applies to co-plaintiffs. A plaintiff might want a very sympathetic co-plaintiff to be part of the same lawsuit; on the other hand, plaintiff might not want to be joined in a lawsuit with a co-plaintiff the presence of whom will in some way undercut the narrative plaintiff wants to present.

While plaintiff gets to choose whom to join, the plaintiff’s choice is not always the final word. First, in some cases, parties can be brought in under Rule 19. In addition, under Rule 24 parties can choose to join the lawsuit as defendants or plaintiffs through intervention.

Rule 21. Misjoinder and Nonjoinder of Parties. Rule 21 is another example of the Federal Rules trying to allow flexibility, and avoiding having results dictated by formalities rather than the ultimate merits. Under the common law, mistakes in joinder could lead to dismissal of a suit. Rule 21 gives the court power to deal flexibly so as to get the right array of parties before the court. As with Rule 17, we will not spend any more time on this.

Rule 22. Interpleader. Imagine you are walking down the street and there it is in front of you - The Magic Water Bottle of Shenzhen. In order to make sure it is not accidentally destroyed or discarded, you pick it up and carry it home. That said, you know it is not yours and you are happy to deliver it to its rightful owner. Imagine, though, that the issue of the rightful owner is not self-evident. Professor Evil steps forward and claims he owns it because he took it from Student A as punishment for the student not paying attention in class. Student A in turn asserts that Professor Evil had no right to take it and she is the true owner because Student B had given it to her when they were dating. Now imagine that Student B shows up and says that he had loaned, not given, the Magic Water Bottle of Shenzhen to Student A and demands that it be returned to him. What are you to do? Alternatively, imagine InsurCo has contractually agreed to provide $1,000,000 in insurance to BigCo. Now imagine that a typhoon hits the factory of BigCo, causing a release of BigCo’s latest production run of AI powered robot watchdogs, who run loose in the town biting people, leading to well more than $1,000,000 in damages.BigCo also has 1,000,000 in damages to its plant. InsurCo agrees that it owes the $1,000,000 under the policy, but doesn’t know who should get it.

In both cases, interpleader is the answer. The asset is placed in the custody of the court, and an interpleader action is used to determine who gets it.

Interpleader can get complicated because it comes in both statutory and a Federal Rules version. For our purposes, it’s enough that you know that this kind of procedural option exists; we will not spend time examing the fine points of how it works.

Rule 24. Intervention. Think back to our discussion under Rule 19. What if, instead of being forced to join the lawsuit, Absentee hears about it and wants to join? Rule 24 provides the means. Intervention as of right resembles Rule 19 in some respects. Setting aside intervention based on a statute, a party may intervene as of right when “claims an interest relating to the property or transaction that is the subject of the action, and is so situated that disposing of the action may as a practical matter impair or impede the movant's ability to protect its interest, unless existing parties adequately represent that interest.” If that fails, a party may intervene with the permission of the court. Note how permissive Rule 24 is. If the court approves, it only takes one “common question of law or fact” for intervention to be proper.

The core idea behind liberal joinder is efficiency. Systems of procedure can embody different choices about what can and should be contained in a single lawsuit. The approach taken by the common law writs, for example, was to severely limit what can be included to a single claim. The federal rules take a very different approach. They support bringing in one lawsuit all claims related to a set of facts.

In allowing broad joinder of claims and parties the federal rules pursue a goal of efficiency. Rather than splitting litigation over one incident into piecemeal litigation, the federal rules support and to some extent require bringing all the claims together for resolution at the same time.

This approach has advantages and costs. The goal of efficiency is indeed served by allowing witness testimony and exhibits to bear on multiple claims against multiple parties. On the other hand, the complexity of litigation that is allowed by the federal rules has costs of its own. Juries may struggle to keep track of how evidence bears on multiple counts, and keeping straight the varying legal standards that might be applied to a single set of facts can also be a challenge. Complexity also can arise in pretrial proceedings, as both discovery and motion practice are complicated by sorting through the many different kinds of claims that can be brought.

Nonetheless, the federal rules have firmly embraced liberal joinder of claims and parties. While you should bring your systems engineer mindset to bear on whether you agree this is a good idea, we also need to work through how the system established under the federal rules operates.

Mandatory and Compulsory – Litigant Choice. One aspect of the federal rules is the degree to which bringing claims into the same lawsuit is forced by mandatory joinder rules or merely allow by permissive joinder rules. This encompasses not just the rules themselves, but also doctrines that operate aside from the rules.

One of those doctrines is claim preclusion, also known as res judicata. Claim preclusion operates to prevent relitigation of the same claim over and over again. Put simply if you bring a lawsuit and lose – or win – you cannot bring exactly that claim again in hopes of the different and better result. Back in the days of the common law writs, claim preclusion barred relitigation of the same writ. At the same time, pleading under the writs allowed coming back to court with a different writ if the claim was barred because the wrong writ had been asserted.

Today, that is not the rule. Today, any claim arising from the same transaction or occurrence that could have been brought at the time the original lawsuit was brought will be barred under the doctrine of claim preclusion. For our purposes here, this means that as a practical matter litigants are not only permitted but effectively required to bring any causes of action relating to a transaction or occurrence or lose them forever. We will return to the issue of claim preclusion later in the course, but for now you can think of claim preclusion as akin to a rule that requires claimants to bring all claims arising from the same transaction or occurrence that can be brought in that forum or lose them. Think of it as a "use it or lose it" requirement with regard to all claims against the defendant arising from the transaction or occurrence that can be brought in that court, regardless of the legal theory.

A similar rule operates both under the doctrine of claim preclusion and under the rules with regard to counterclaims. Rule 13 covers counterclaims, and divides them into mandatory and permissive counterclaims. Mandatory counterclaims are those that arise from the same transaction or occurrence as the plaintiff’s claim. Rule 13 a requires that these counterclaims be brought in the federal action or lost forever. Put differently, a defendant cannot choose to file a separate action asserting what might be mandatory counterclaims, nor can the defendant save the counterclaim for use later. A use it here and now or lose it rule applies.

Other claims that might be brought are permissive. For example, neither plaintiffs nor defendants are required to bring in the same action any unrelated claims they may have, but they may bring those claims (assuming subject matter jurisdiction, personal jurisdiction, and venue). A defendant may bring as a permissive counterclaim any claim she has against the plaintiff, regardless of whether or not it is related in any way to the plaintiff’s claim against the defendant. (Note, as we will discuss below, that the other elements of selecting a proper courts must still be established).

Cross-claims are also permissive. A cross-claim is a claim that one defendant has against another defendant or that one plaintiff has against another plaintiff. As we will see, the first such cross-claim needs to arise from the same transaction or occurrence as an original claim by the plaintiff. Even though such a cross claim is related to the overall litigation, the cross claimant can choose to file it in another location or at a later time.

Also not mandatory are claims where a party seeks to implead another. In some cases, the defendant might be able to claim that if it is liable, another party is liable to it. We saw such a claim in the Asahi case where the tire manufacturer impleaded the manufacturer of the valve on the tire. While impleading is permitted, it is not required, and can be pursued as a separate action.

Permissive joinder also applies to joinder of parties. In general, a claimant is not required to join in the action every potentially liable defendant. There are some cases where party is considered under rule 19 to be both necessary and indispensable, but in the average run-of-the-mill case where there are multiple, potentially liable defendants, the plaintiff can choose which one or ones it chooses to pursue.

Again, bring your systems engineer eye to the issue of mandatory and permissive joinder of claims and parties. From a system standpoint, when does it make sense to require claims and parties to be joined in a single action whether or not the parties prefer it, and when does it make sense to allow them to make their own decisions?

Overlap with PJ, SMJ, Venue. An important thing to remember about joinder of claims and parties is that the federal rules only apply is that the federal rules do not displace or set aside the other doctrines that govern where and how a case may be brought. These requirements still apply. For each claim, personal jurisdiction, venue, and subject matter jurisdiction must be established.

For counterclaims, plaintiffs have been held unable to object to venue or personal jurisdiction. This may be seen as a kind of waiver, as plaintiff did choose the initial forum. Subject matter jurisdiction is an absolute requirement for all claims.

Joinder of Claims Reviewed.

Be able to fill in the following chart.

|

Joinder of Claims Device & FRCP No. |

Definition? |

Who Uses? (P , D or both?) |

Elements? |

Mandatory? |

|

1. 18a (the “kitchen sink” rule) |

||||

|

2. 13(g) Crossclaims |

||||

|

3a. 13(a) compulsory counterclaims |

||||

|

3b. 13(b) permissive counterclaims |

||||

|

4. 20(a) Joinder |

||||

|

5. 13(h) Joinder |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. 14a & b 3rd party claim/ impleader |

11.3 Joinder - Selected Rules 11.3 Joinder - Selected Rules

With the overview above fresh in your mind, read through the applicable rules that are relevant to our inquiry. Be sure to pay close attention to the language for those rules we will spend time with.

11.3.1 Rule 13. Counterclaim and Crossclaim 11.3.1 Rule 13. Counterclaim and Crossclaim

(a) Compulsory Counterclaim.

(1) In General. A pleading must state as a counterclaim any claim that—at the time of its service—the pleader has against an opposing party if the claim:

(A) arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the opposing party's claim; and

(B) does not require adding another party over whom the court cannot acquire jurisdiction.

(2) Exceptions. The pleader need not state the claim if:

(A) when the action was commenced, the claim was the subject of another pending action; or

(B) the opposing party sued on its claim by attachment or other process that did not establish personal jurisdiction over the pleader on that claim, and the pleader does not assert any counterclaim under this rule.

(b) Permissive Counterclaim. A pleading may state as a counterclaim against an opposing party any claim that is not compulsory.

(c) Relief Sought in a Counterclaim. A counterclaim need not diminish or defeat the recovery sought by the opposing party. It may request relief that exceeds in amount or differs in kind from the relief sought by the opposing party.

(d) Counterclaim Against the United States. These rules do not expand the right to assert a counterclaim—or to claim a credit—against the United States or a United States officer or agency.

(e) Counterclaim Maturing or Acquired After Pleading. The court may permit a party to file a supplemental pleading asserting a counterclaim that matured or was acquired by the party after serving an earlier pleading.

(f) [Abrogated. ]

(g) Crossclaim Against a Coparty. A pleading may state as a crossclaim any claim by one party against a coparty if the claim arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the original action or of a counterclaim, or if the claim relates to any property that is the subject matter of the original action. The crossclaim may include a claim that the coparty is or may be liable to the crossclaimant for all or part of a claim asserted in the action against the crossclaimant.

(h) Joining Additional Parties. Rules 19 and 20 govern the addition of a person as a party to a counterclaim or crossclaim.

(i) Separate Trials; Separate Judgments. If the court orders separate trials under Rule 42(b), it may enter judgment on a counterclaim or crossclaim under Rule 54(b) when it has jurisdiction to do so, even if the opposing party's claims have been dismissed or otherwise resolved.

11.3.2 Rule 14. Third-Party Practice 11.3.2 Rule 14. Third-Party Practice

a) When a Defending Party May Bring in a Third Party.

(1) Timing of the Summons and Complaint. A defending party may, as third-party plaintiff, serve a summons and complaint on a nonparty who is or may be liable to it for all or part of the claim against it. But the third-party plaintiff must, by motion, obtain the court's leave if it files the third-party complaint more than 14 days after serving its original answer.

(2) Third-Party Defendant's Claims and Defenses. The person served with the summons and third-party complaint—the “third-party defendant”:

(A) must assert any defense against the third-party plaintiff's claim under Rule 12;

(B) must assert any counterclaim against the third-party plaintiff under Rule 13a, and may assert any counterclaim against the third-party plaintiff under Rule 13(b) or any crossclaim against another third-party defendant under Rule 13(g);

(C) may assert against the plaintiff any defense that the third-party plaintiff has to the plaintiff's claim; and

(D) may also assert against the plaintiff any claim arising out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the plaintiff's claim against the third-party plaintiff.

(3) Plaintiff's Claims Against a Third-Party Defendant. The plaintiff may assert against the third-party defendant any claim arising out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the plaintiff's claim against the third-party plaintiff. The third-party defendant must then assert any defense under Rule 12 and any counterclaim under Rule 13(a), and may assert any counterclaim under Rule 13(b) or any crossclaim under Rule 13(g).

(4) Motion to Strike, Sever, or Try Separately. Any party may move to strike the third-party claim, to sever it, or to try it separately.

(5) Third-Party Defendant's Claim Against a Nonparty. A third-party defendant may proceed under this rule against a nonparty who is or may be liable to the third-party defendant for all or part of any claim against it.

(6) Third-Party Complaint In Rem. If it is within the admiralty or maritime jurisdiction, a third-party complaint may be in rem. In that event, a reference in this rule to the “summons” includes the warrant of arrest, and a reference to the defendant or third-party plaintiff includes, when appropriate, a person who asserts a right under Supplemental Rule C(6)(a)(i) in the property arrested.

(b) When a Plaintiff May Bring in a Third Party. When a claim is asserted against a plaintiff, the plaintiff may bring in a third party if this rule would allow a defendant to do so.

(c) Admiralty or Maritime Claim.

(1) Scope of Impleader. If a plaintiff asserts an admiralty or maritime claim under Rule 9(h), the defendant or a person who asserts a right under Supplemental Rule C(6)(a)(i) may, as a third-party plaintiff, bring in a third-party defendant who may be wholly or partly liable—either to the plaintiff or to the third-party plaintiff— for remedy over, contribution, or otherwise on account of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences.

(2) Defending Against a Demand for Judgment for the Plaintiff. The third-party plaintiff may demand judgment in the plaintiff's favor against the third-party defendant. In that event, the third-party defendant must defend under Rule 12 against the plaintiff's claim as well as the third-party plaintiff's claim; and the action proceeds as if the plaintiff had sued both the third-party defendant and the third-party plaintiff

11.3.3 Rule 18. Joinder of Claims 11.3.3 Rule 18. Joinder of Claims

(a) In General. A party asserting a claim, counterclaim, crossclaim, or third-party claim may join, as independent or alternative claims, as many claims as it has against an opposing party.

(b) Joinder of Contingent Claims. A party may join two claims even though one of them is contingent on the disposition of the other; but the court may grant relief only in accordance with the parties’ relative substantive rights. In particular, a plaintiff may state a claim for money and a claim to set aside a conveyance that is fraudulent as to that plaintiff, without first obtaining a judgment for the money.

11.3.4 Rule 19. Required Joinder of Parties 11.3.4 Rule 19. Required Joinder of Parties

(a) Persons Required to Be Joined if Feasible.

(1) Required Party. A person who is subject to service of process and whose joinder will not deprive the court of subject-matter jurisdiction must be joined as a party if:

(A) in that person's absence, the court cannot accord complete relief among existing parties; or

(B) that person claims an interest relating to the subject of the action and is so situated that disposing of the action in the person's absence may:

(i) as a practical matter impair or impede the person's ability to protect the interest; or

(ii) leave an existing party subject to a substantial risk of incurring double, multiple, or otherwise inconsistent obligations because of the interest.

(2) Joinder by Court Order. If a person has not been joined as required, the court must order that the person be made a party. A person who refuses to join as a plaintiff may be made either a defendant or, in a proper case, an involuntary plaintiff.

(3) Venue. If a joined party objects to venue and the joinder would make venue improper, the court must dismiss that party.

(b) When Joinder Is Not Feasible. If a person who is required to be joined if feasible cannot be joined, the court must determine whether, in equity and good conscience, the action should proceed among the existing parties or should be dismissed. The factors for the court to consider include:

(1) the extent to which a judgment rendered in the person's absence might prejudice that person or the existing parties;

(2) the extent to which any prejudice could be lessened or avoided by:

(A) protective provisions in the judgment;

(B) shaping the relief; or

(C) other measures;

(3) whether a judgment rendered in the person's absence would be adequate; and

(4) whether the plaintiff would have an adequate remedy if the action were dismissed for nonjoinder.

{c) Pleading the Reasons for Nonjoinder. When asserting a claim for relief, a party must state:

(1) the name, if known, of any person who is required to be joined if feasible but is not joined; and

(2) the reasons for not joining that person.

(d) Exception for Class Actions. This rule is subject to Rule 23.

11.3.5 Rule 20. Permissive Joinder of Parties 11.3.5 Rule 20. Permissive Joinder of Parties

(a) Persons Who May Join or Be Joined.

(1) Plaintiffs. Persons may join in one action as plaintiffs if:

(A) they assert any right to relief jointly, severally, or in the alternative with respect to or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences; and

(B) any question of law or fact common to all plaintiffs will arise in the action.

(2) Defendants. Persons—as well as a vessel, cargo, or other property subject to admiralty process in rem—may be joined in one action as defendants if:

(A) any right to relief is asserted against them jointly, severally, or in the alternative with respect to or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences; and

(B) any question of law or fact common to all defendants will arise in the action.

(3) Extent of Relief. Neither a plaintiff nor a defendant need be interested in obtaining or defending against all the relief demanded. The court may grant judgment to one or more plaintiffs according to their rights, and against one or more defendants according to their liabilities.

(b) Protective Measures. The court may issue orders—including an order for separate trials—to protect a party against embarrassment, delay, expense, or other prejudice that arises from including a person against whom the party asserts no claim and who asserts no claim against the party.

11.3.6 Rule 21. Misjoinder and Nonjoinder of Parties 11.3.6 Rule 21. Misjoinder and Nonjoinder of Parties

Misjoinder of parties is not a ground for dismissing an action. On motion or on its own, the court may at any time, on just terms, add or drop a party. The court may also sever any claim against a party.

11.3.7 Rule 22. Interpleader 11.3.7 Rule 22. Interpleader

(a) Grounds.

(1) By a Plaintiff. Persons with claims that may expose a plaintiff to double or multiple liability may be joined as defendants and required to interplead. Joinder for interpleader is proper even though:

(A) the claims of the several claimants, or the titles on which their claims depend, lack a common origin or are adverse and independent rather than identical; or

(B) the plaintiff denies liability in whole or in part to any or all of the claimants.

(2) By a Defendant. A defendant exposed to similar liability may seek interpleader through a crossclaim or counterclaim.

{b) Relation to Other Rules and Statutes. This rule supplements—and does not limit—the joinder of parties allowed by Rule 20. The remedy this rule provides is in addition to—and does not supersede or limit—the remedy provided by 28 U.S.C. §§1335, 1397, and 2361. An action under those statutes must be conducted under these rules.

11.3.8 Rule 24. Intervention 11.3.8 Rule 24. Intervention

(a) Intervention of Right. On timely motion, the court must permit anyone to intervene who:

(1) is given an unconditional right to intervene by a federal statute; or

(2) claims an interest relating to the property or transaction that is the subject of the action, and is so situated that disposing of the action may as a practical matter impair or impede the movant's ability to protect its interest, unless existing parties adequately represent that interest.

(b) Permissive Intervention.

(1) In General. On timely motion, the court may permit anyone to intervene who:

(A) is given a conditional right to intervene by a federal statute; or

(B) has a claim or defense that shares with the main action a common question of law or fact.

(2) By a Government Officer or Agency. On timely motion, the court may permit a federal or state governmental officer or agency to intervene if a party's claim or defense is based on:

(A) a statute or executive order administered by the officer or agency; or

(B) any regulation, order, requirement, or agreement issued or made under the statute or executive order.

(3) Delay or Prejudice. In exercising its discretion, the court must consider whether the intervention will unduly delay or prejudice the adjudication of the original parties’ rights.

(c) Notice and Pleading Required. A motion to intervene must be served on the parties as provided in Rule 5. The motion must state the grounds for intervention and be accompanied by a pleading that sets out the claim or defense for which intervention is sought.

11.4 Joinder - Selected Illustrative Cases 11.4 Joinder - Selected Illustrative Cases

11.4.1 Pace v. Timmermann's Ranch & Saddle Shop Inc. 11.4.1 Pace v. Timmermann's Ranch & Saddle Shop Inc.

Jeanne PACE and Dan Pace, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. TIMMERMANN’S RANCH AND SADDLE SHOP INC., et al., Defendants-Appellees.

No. 14-1940.

United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit.

Argued Oct. 29, 2014.

Decided Aug. 4, 2015.

*749Robert A. Handelsman, Chicago, IL, for Plaintiffs-Appellants.

David F. Ryan, Patton & Ryan, Chicago, IL, for Defendants-Appellees.

Before RIPPLE, KANNE, and SYKES, Circuit Judges.

In 2011, Timmermann’s Ranch and Saddle Shop (“Timmermann’s”) brought an action against its former employee, Jeanne Pace, for conversion, breach of fiduciary duty, fraud, and unjust enrichment. It alleged that Ms. Pace had stolen merchandise and money from the company. Ms. Pace filed her answer and a counterclaim in early 2011.

In 2013, Ms. Pace and Dan Pace, her husband, filed a separate action against Timmermann’s and four of its employees, Dale Timmermann, Carol Timmermann, Dawn Manley, and Tammy Rigsby (collectively “the individual defendants”). They alleged that these defendants had conspired to facilitate Ms. Pace’s false arrest. Ms. Pace alleged that, as a result of their actions, she had suffered severe and extreme emotional distress. Mr. Pace claimed a loss of consortium.

Ms. Pace filed a motion to consolidate these two actions. The court granted the motion with respect to discovery, but denied the motion with respect to trial and instructed Ms. Pace that she should request consolidation for trial after the close of discovery. In the midst of discovery, however, the district court dismissed Ms. Pace’s 2013 action after concluding that her claims were actually compulsory counterclaims that should have been filed with her answer to the company’s 2011 complaint. Ms. Pace appeals the dismissal of her 2013 action and the court’s denial of her motion to consolidate.

We hold that Ms. Pace’s claims against parties other than Timmermann’s were not compulsory counterclaims because Federal *750Rules of Civil Procedure 13 and 20, in combination, do not compel a litigant to join additional parties to bring what would otherwise be a compulsory counterclaim. We also hold that because Ms. Pace’s claim for abuse of process against Timmermann’s arose prior to the filing of her counterclaim, it was a mandatory counterclaim. We therefore affirm in part and reverse in part the judgment of the district court and remand the ease for further proceedings.

I

BACKGROUND

A.

The issues in this case present a somewhat complex procedural situation. For ease of reading, we first will set forth the substantive allegations of each party. Then, we will set forth the procedural history of this litigation in the district court.

1.

Timmermann’s boards, buys, and sells horses, as well as operates both a ranch and a “saddle shop,” in which it sells merchandise for owners and riders of horses. When this dispute arose, Carol and Dale Timmermann managed Timmermann’s. Dawn Manley and Tammy Rigsby were employees of Timmermann’s.

In its 2011 complaint, Timmermann’s alleged that, while employed as a bookkeeper at Timmermann’s, Ms. Pace had embezzled funds and stolen merchandise. According to the complaint, beginning at an unknown time, Ms. Pace regularly began removing merchandise from Timmer-mann’s without paying; she would then sell those articles on eBay for her personal benefit. Timmermann’s further alleged that it discovered that Ms. Pace was selling items on eBay through a private sting operation.

According to the complaint, in February 2011, a Timmermann’s employee discovered some of the company’s merchandise in Ms. Pace’s car. At this point, Timmer-mann’s fired Ms. Pace. Thereafter, during a review of its records, including the checking account maintained by Ms. Pace, Timmermann’s discovered that a check that Ms. Pace had represented as being payable to a hay vendor actually had been made payable to cash. Timmermann’s also discovered that, on at least eight occasions, Ms. Pace had utilized the company’s business credit card to make personal purchases.

2.

In her 2013 complaint, Ms. Pace alleged that her conduct while working at Timmer-mann’s was consistent with its usual course of business. She stated that Tim-mermann’s had a practice of allowing employees to use cash to purchase merchandise at cost or, alternatively, by deducting the merchandise’s value from the employee’s pay. She maintains that she had purchased the company’s merchandise under that established practice. She also alleged that Carol Timmermann, her supervisor, knew that she had sold the company’s merchandise at flea markets and never had objected.

Ms. Pace also maintained that she was instructed to write corporate checks out to cash and to note the payee in the check records. Pursuant to those instructions, Ms. Pace had written checks to cash and recorded the payee and purpose of the check in the check records. Ms. Pace further alleged that Carol Timmermann had instructed her to use Carol’s credit card, which was used as the corporate credit card, for personal purchases and to reimburse Carol, and not Timmermann’s, for those purchases.

*751According to Ms. Pace’s complaint, on February 14, 2011, Dale Timmermann called the Lake County, Illinois, Sheriffs Office and accused Ms. Pace of stealing over $100,000 in merchandise from Tim-mermann’s. On February 14 and 15, Dale Timmermann took affirmative steps to convince the Sheriffs Office to arrest Ms. Pace by stating that Ms. Pace had stolen approximately $100,000 in merchandise and that Ms. Pace had been changing inventory on the computer. Ms. Pace was taken into custody by the Lake County Sheriffs Office on February 15, 2011, and released on February 16.

Following her release from custody, the individual defendants continued to provide the Sherriffs Office with information about Ms. Pace’s allegedly unlawful conduct. On March 13, 2012, the State’s Attorney brought charges against Ms. Pace premised on the information provided by the company’s employees. Ms. Pace was charged with theft, forgery, and unlawful use of a credit card.

B.

We turn now to the procedural history of this litigation in the district court, a history that produced the situation before us today.

On March 3, 2011, Timmermann’s filed its civil complaint against Ms. Pace, alleging conversion, breach of fiduciary duty, fraud, and unjust enrichment. It sought to recover the value of the merchandise and money that Ms. Pace allegedly had stolen. Ms. Pace filed her answer and counterclaims on April 5, 2011.

On February 1, 2013, Ms. Pace and Mr. Pace (collectively “the Paces”) filed a complaint against Timmermann’s and the individual defendants, alleging that they had conspired to facilitate Ms. Pace’s false arrest. Ms. Pace alleged that she had suffered severe and extreme emotional distress; Mr. Pace claimed a loss of consortium. Specifically, the Paces’ complaint included seven counts: “false arrest/false imprisonment/in concert liability” (Count I); “abuse of process” (Count II); “intentional infliction of emotional distress” (Count III); “conspiracy to commit abuse of process and intentional infliction of emotional distress” (Count IV); “in concert activity” (Count V); “aiding and abetting abuse of process and intentional infliction of emotional distress” (Count VI); and “loss of consortium” (Count VII).1 Only four counts, Counts I — III and Count VII, listed Timmer-mann’s as a defendant. The remaining counts were directed at Dale and Carol Timmermann or the other individual defendants.

On March 15, 2013, Ms. Pace filed a motion to consolidate the two cases. On April 2, 2013, the district court Consolidated the cases for the purpose of discovery and pretrial practice. The court denied without prejudice the motion to consolidate the cases for trial; it stated that it would rule on a motion to consolidate for trial after discovery.

On May 2, 2013, Timmermann’s and the individual defendants moved to dismiss Ms. Pace’s action under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) and 13(a). They contended that her allegations should have been filed as compulsory counterclaims in the 2011 action. Thereafter, Ms. Pace moved to amend her 2011 counterclaim and to consolidate the cases for trial. The district court set a briefing schedule for the company’s motion to dismiss and held Ms. Pace’s motion to consolidate in abeyance.

In December 2013, the district court granted the company’s motion to dismiss. *752The court concluded that Ms. Pace’s separate claims were barred because they were compulsory counterclaims that should have been brought in the 2011 action because the claims arose out of the same transaction or occurrence. Noting that her 2013 complaint had indicated that the fear of being indicted caused her emotional distress, the court held that Ms. Pace’s claims were in existence when the 2011 action was filed; it therefore rejected Ms. Pace’s argument that her abuse-of-process claim was not in existence until she was charged. In the district court’s view, the absence of Mr. Pace and the individual defendants from the 2011 action did not preclude the court’s conclusion that Ms. Pace’s claims were compulsory counterclaims because Mr. Pace and the individual defendants could have been joined in the 2011 action under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 20.2

II

DISCUSSION

The Paces now appeal the dismissal of the 2013 action. They concede that Ms. Pace’s false arrest and emotional distress claims against Timmermann’s were compulsory counterclaims and therefore properly dismissed. They contend, however, that Ms. Pace’s claims against the individual defendants and Mr. Pace’s claims for loss of consortium were not compulsory counterclaims. They also submit that Ms. Pace’s abuse of process claim against Tim-mermann’s did not “exist” when the 2011 action was filed and therefore could not have been a compulsory counterclaim.

“We review de novo [a] district court’s grant of a motion to dismiss.” Thulin v. Shopko Stores Operating Co., LLC, 771 F.3d 994, 997 (7th Cir.2014); see also Transamerica Occidental Life Ins. Co. v. Aviation Office of Am., Inc., 292 F.3d 384, 389 (3d Cir.2002) (“[W]e review de novo the District Court’s determination that [the] suit should have been pursued as a compulsory counterclaim in the [prior] action.”).'

A.

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 13 governs compulsory counterclaims. Rule 13(a)(1) provides:

In General. A pleading must state as a counterclaim any claim that — at the time of its service — the pleader has against an opposing party if the claim:

(A) arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the opposing party’s claim; and

(B) does not require adding another party over whom the court cannot acquire jurisdiction.

The text of this subsection limits the definition of compulsory counterclaim to those claims that the pleader has against an opposing party; it does not provide for the joinder of parties. Instead, in a later subsection, it expressly incorporates the standards set out for the required joinder of parties under Rule 19 and the permissive joinder of parties under Rule 20. Specifically, subsection 13(h) provides: “Rules 19 and 20 govern the addition of a person as a party to a counterclaim or crossclaim.”

Rule 19 requires that a party be joined if, “in that person’s absence, the court cannot accord complete relief among existing parties,” or if proceeding in the party’s absence may “impair or impede the person’s ability to protect [his] interest” or “leave an existing party subject to a substantial risk of incurring double, multiple, or otherwise inconsistent obligations.” Fed.R.Civ.P. 19(a)(1). In contrast, Rule *75320 allows for parties to be joined if “any right to relief is asserted against them jointly, severally, or in the alternative with respect to or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences; and ... any question of law or fact common to all defendants will arise in the action.”3 Fed.R.Civ.P. 20(a)(2).

The district court did not hold, and Tim-mermann’s does not contend, that the individual defendants named in Ms. Pace’s complaint were opposing parties under Rule 13(a) in the 2011 action.4 Nor does the company’s claim that the individual defendants were required parties under Rule 19. Instead, Timmermann’s submits that, because the district court could have acquired jurisdiction over the individual defendants and could have joined them under Rule 20, it was appropriate to treat Ms. Pace’s claims as compulsory counterclaims. In essence, Timmermann’s combines the permissive joinder rule under Rule 20 with the compulsory counterclaim requirement in Rule 13 to create a rule for compulsory joinder.

The text of the rules, however, do not permit such an arrangement. Timmermann’s relies on the text of Rule 13(a)(1)(B), which provides that a claim is not a compulsory counterclaim if it “require[s] adding another party over whom the court cannot acquire jurisdiction.” Fed.R.Civ.P. 13(a)(1)(B). From this statement, Timmermann’s devises that, because the district court could have exercised jurisdiction over the individual defendants, the claims against them must be brought as compulsory counterclaims.5 Rule 13, *754however, does not require the joinder of parties. Its scope is limited to the filing of counterclaims. Although Rule 13(a)(1)(B), like Rule 19, encourages that all claims be resolved in one action with all the interested parties before the court,6 Rule 13 fulfills this objective by allowing, not mandating, that a defendant bring counterclaims that require additional parties.7 Whether a party must be joined in an action continues to be governed only by Rule 19. Rule 13(a)(1)(B) does not transform Rule 20 into a mandatory joinder rule.

The history of Rule 13 supports our conclusion that Rule 13 does not provide for compulsory joinder. Prior to 1966, Rule 13(h) read:

When the presence of parties other than those to the original action is required for the granting of complete relief in the determination of a counterclaim or cross-claim, the court shall order them to be brought in as defendants as provided in these rules, if jurisdiction of them can be obtained and their joinder will not deprive the court of jurisdiction of-the action.

As then written, Rule 13(h) was interpreted as an additional mandatory joinder rule, similar to Rule 19, which required that necessary parties be joined.8 To correct this use of Rule 13, subdivision (h) was amended in 1966 to provide: “Joinder of Additional Parties. Persons other than those made parties to the original action may be made parties to a counterclaim or cross-claim in accordance with the provisions of Rules 19 and 20.” In the note accompanying the amendment, the committee noted that Rule 13(h) had previously failed to reference that Rule 20 allows for the permissive joinder of parties. The committee continued:

The amendment of Rule 13(h) supplies the latter omission by expressly referring to Rule 20, as amended, and also incorporates by direct reference the revised criteria and procedures of Rule 19, as amended. Hereafter, for the purpose of determining who must or may be joined as additional parties to a counterclaim or cross-claim, ... amended Rules 19 and 20 are to be applied in the usual fashion.

Fed.R.Civ.P. 13 advisory committee’s note to 1966 amendment.9 The committee note thus highlights the limited nature of Rule 13, which operates only with regard to claims and does not mandate or otherwise influence the joinder of parties. The rule, supported by its accompanying note, di*755rects litigants to the framework under Rules 19 and 20, respectively, if they wish to join parties. To hold that Rule 13 compels the joinder of additional parties through the use of Rule 20 would read the term “opposing party” out of Rule 13(a).10

Requiring Ms. Pace to bring the claims against the individual defendants as a counterclaim in the initial action might well serve judicial economy, but the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure do not require such a result.11 The Rules strike a deli*756cate balance between (1) a plaintiffs interest in structuring litigation, (2) a defendant’s “wish to avoid multiple litigation, or inconsistent relief,” (3) an outsider’s interest in joining the litigation, and (4) “the interest of the courts and the public in complete, consistent, and efficient settlement of controversies.” Provident Tradesmens Bank & Tr. Co. v. Patterson, 390 U.S. 102, 109-11, 88 S.Ct. 733, 19 L.Ed.2d 936 (1968).12 The rules generally allow for a plaintiff to decide who to join in an action. See Applewhite v. Reichhold Chems., Inc., 67 F.3d 571, 574 (5th Cir.1995). A plaintiffs interest in structuring litigation is overridden only when the prejudice to the defendant or an absent party is substantial and cannot be avoided. See Fed.R.Civ.P. 19(b); see also Provident Tradesmens Bank & Tr. Co., 390 U.S. at 124-25, 88 S.Ct. 733. Otherwise, the threat of duplicative litigation generally is insufficient to override a plaintiffs interest in this regard.

Indeed, if Ms. Pace had brought her claim before Timmermann’s filed suit, she could have chosen to file separate actions against Timmermann’s and the individual defendants. See Temple v. Synthes Corp., 498 U.S. 5, 7, 111 S.Ct. 315, 112 L.Ed.2d 263 (1990) (per curiam) (noting that “[i]t has long been the rule that it is not necessary for all joint tortfeasors to be named as defendants in a single lawsuit”); see also Fed.R.Civ.P. 19 advisory committee’s note to 1966 amendment (stating that the rule “is not at variance with the settled authorities holding that a tortfeasor with the usual ‘joint-and-several’ liability is merely a permissive party to an action against another with like liability” and that the “[jjoinder of these tortfeasors continues to be regulated by Rule 20”).13 It *757makes little sense to require Ms. Pace to join the individual defendants under Rule 20 in order to bring all of her claims in the same action when, if she initially had been the plaintiff, she would not have been required to join those same parties.14

Timmermann’s recognizes that Rule 20 does not require a litigant to join additional parties.15 Therefore, because a party is not required to join additional parties under Rules 13 or 20, the district court erred by barring Ms. Pace’s claims against the individual defendants and Mr. Pace’s claims for failing to join them when she brought her counterclaim.

B.

We turn now to whether the district court appropriately characterized Ms. Pace’s claim against Timmermann’s for abuse of process as a compulsory counterclaim. Ms. Pace submits that her abuse of process claim did not exist until there was “process” in the form of an information or indictment. She contends that the facts alleged in the 2013 complaint that occurred before she was charged only demonstrated one element of the claim, the defendants’ mens rea. “In order to be a compulsory counterclaim, Rule 13(a) requires that a claim ... exist at the time of pleading_” Burlington N. R.R. Co. v. Strong, 907 F.2d 707, 710 (7th Cir.1990). Thus, “a party need not assert ... a compulsory counterclaim if it has not matured when the party serves his answer.” Id. at 712.

Under Illinois law, “[t]he only elements necessary to plead a cause of action for abuse of process are: (1) the existence of an ulterior purpose or motive and (2) some act in the use of legal process not .proper in the regular prosecution of the proceedings.” Kumar v. Bornstein, 354 Ill.App.3d 159, 290 Ill.Dec. 100, 820 N.E.2d 1167, 1173 (2004) (emphasis in *758original). Although neither an indictment nor an arrest is a necessary element to bring an abuse of process’ claim' under Illinois law, a plaintiff is required to plead some improper use of legal process. See id. To satisfy this requirement, a plaintiff must plead facts that “show that the process was used to accomplish some result that is beyond the purview of the process.” Id. In most circumstances, this requirement is met through an arrest or physical seizure of property. See id. (noting that “the relevant case law generally views an actual arrest or seizure of property as a sufficient fact to state a claim of abuse of process” (emphasis in original)).

Ms. Pace was arrested on.February 15, 2011. The company’s 2011 complaint was filed on March 3, 2011, and Ms. Pace filed her answer and counterclaim on April 5, 2011. Consequently, the only fact not in Ms. Pace’s possession at the time she filed ,her answer was the March 13, 2012 information. Illinois courts are clear, however, that an arrest is sufficient to bring an abuse of process claim. See id. Ms. Pace’s abuse of process claim therefore matured when she was arrested, which occurred before she filed her responsive pleading. Her failure to raise the abuse of process claim as a counterclaim along with her answer therefore contravenes Rule 13.

Indeed, in alleging an abuse of process, Ms. Pace primarily relies on her 2011 arrest, and not on the fact that she was charged. The complaint alleges that the defendants intentionally injured and caused injury to Ms. Pace by giving “false information to law enforcement and explicitly or implicitly urgfing] the arrest and/or the indictment of [Ms. Pace].”16 The complaint makes it clear that Ms. Pace could have brought her claim following her 2011 arrest, and thus, her abuse of process claim matured at that time.

Because we conclude that the district court erred in dismissing both Ms. Pace’s claims against the individual defendants and Mr. Pace’s claims, we need not address the party’s arguments about Ms. Pace’s motion to consolidate. The district court will have the opportunity to consider the motion to consolidate on remand.

Conclusion

We conclude that the district court erred in dismissing the Paces’ 2013 complaint in its entirety. Because neither Rule 13 nor Rule 20 provide for compulsory joinder, Ms. Pace’s claims against the individual defendants and Mr. Pace’s claims for loss of consortium were not compulsory counterclaims. Ms. Pace’s abuse of process claim against Timmermann’s was in existence when Ms. Pace filed her 2011 answer and counterclaim, and therefore the district court was correct to bar her subsequent abuse of process claim against Tim-mermann’s. The judgment of the district court is therefore affirmed in part and reversed in part and the case is remanded for proceedings consistent with this opinion. Ms. Pace may recover her costs in this appeal.

AFFIRMED IN PART, REVERSED AND REMANDED IN PART.

11.4.2 M.K. v. Tenet 11.4.2 M.K. v. Tenet

M.K. et al., Plaintiffs, v. George TENET, Director, Central Intelligence Agency, et al., Defendants.

No. CIV.A. 99-0095(RMU).

United States District Court, District of Columbia.

July 30, 2002.

*135 MEMORANDUM OPINION

Granting the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Amend the Complaint; Denying the Defendants’ Motion to Sever

I. INTRODUCTION

Employees of the United States Central Intelligence Agency (“CIA”) brought this as-yet-uncertified class action against that agency, that agency’s director, George Tenet, and 30 unnamed “John and Jane Does” (collectively “the defendants”). In a four-count amended complaint, six plaintiffs allege that the CIA violated the Privacy Act of 1974, as amended, 5 U.S.C. § 552a (“Privacy Act”), and several of their constitutional rights. In a proposed second amended complaint, which is a subject of this memorandum opinion, 15 plaintiffs altogether1 allege that the CIA obstructs the plaintiffs’ efforts to obtain assistance of counsel, thereby causing an invasion of privacy among other alleged violations of the Constitution. Additionally, the proposed second amended complaint states that beginning in 1997, the defendants’ policy and practice associated with the alleged obstruction of counsel violates the Privacy Act. Furthermore, the plaintiffs claim that the defendants’ alleged practice of obstruction of counsel violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000 et seq (“Title VII”). Before the court is the plaintiffs’ motion to amend the complaint with their proposed second amended complaint pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 15, and the defendants’ motion to sever the claims of the six existing plaintiffs pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 21. After consideration of the parties’ submissions and the relevant law, the court grants the plaintiffs’ motion to amend the complaint and denies the defendants’ motion to sever.

II. BACKGROUND

A. Factual Background

On January 13, 1999, plaintiffs M.K. and Evelyn M. Conway filed the complaint initiating the present action. On April 12, 1999, the plaintiffs filed an amended complaint adding M.D.E., R.B., Grace Tilden, Vivian Green, and George D. Mitford as plaintiffs.2 By order dated August 4, 1999, the court approved the voluntary dismissal without prejudice of plaintiff Green’s claims. Order dated August 4, 1999. By order dated March 3, 2000, the court approved the voluntary dismissal without prejudice of plaintiff M.D.E.’s claims. Order dated March 3, 2000. On November 30, 2001, the plaintiffs filed a proposed second amended complaint adding *136J.T., J.B., C.B., P.C., P.C.I., C. Lynn, Nathan (P), Elaine Livingston (P), and Betty E. Ya-les (P) as nine new plaintiffs.3 Second Am. Compl. (“2d Am. Compl”) at 2 n. 2. The court identifies the six existing plaintiffs as M.K., Conway, Tilden, R.B., C.T., and Mitford. Beginning in 1997 and continuing to the present, the plaintiffs claim that the defendants’ acts and omissions in denying the plaintiffs access to effective assistance of counsel violate the plaintiffs’ rights under the First, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments of the United States Constitution, the Privacy Act, and Title VII.2d Am. Compl. 1111 2-5, 444. Specifically, the nine new plaintiffs, in addition to the six existing plaintiffs, allege in the second amended complaint that the defendants’ September 4, 1998 notice entitled “Access to Agency Facilities, Information, and Personnel by Private Attorneys and Other Personal Representatives” deprives the plaintiffs’ counsel access to “official information” pertaining to the plaintiffs’ employment matters. Id. 1123. The defendants’ invocation of the September 4, 1998 notice has allegedly resulted in a denial of the plaintiffs’ access to CIA documents, policies, procedures, and regulations, thereby preventing counsel from effectively advising the plaintiffs of their rights. Id. The plaintiffs claim that the defendants have “willfully and intentionally failed to maintain accurate, timely, and complete records pertaining to the plaintiffs in their personnel, security, and medical files so as to ensure fairness to [the] plaintiffs, thus failing to comply with 5 U.S.C. § 552a(e)(5) [of the Privacy Act].” Am. Compl. 11116. What follows are the six existing plaintiffs’ factual allegations relating to the inaccuracy of the records in question.

Plaintiff M.K. complains of a letter of reprimand placed in her personnel file in April 1997, which concerns her responsibility for the loss of top-secret information contained on laptop computers sold at an auction. Id. 111115, 116a. Plaintiff Conway complains of a finding by the CIA Human Resources Staff or Personnel Evaluation Board concerning her ineligibility for foreign assignment. Id. HH23, 116b. Plaintiff Conway additionally avers that the CIA notified her of this finding in March 1997. Id. 1123.

Plaintiff C.T. complains of a Board of Inquiry determination that she was not qualified for the position she held with the CIA. Id. H1167, 116e. This Board of Inquiry convened after “early 1998.” Id. 111166-67. Plaintiff Mitford complains of receiving two negative Performance Appraisal Reports and two negative “spot reports” on unspecified dates in 1997, allegedly based on false information. Id. 111181, 116g. Plaintiff R.B. complains of inaccurate counter-intelligence and polygraph information contained in his file. Id. H 116f. Plaintiff R.B.’s last polygraph exam took place in February 1996. Id. H 76. Plaintiff Tilden makes no allegations relating to Count IV of the amended complaint (‘Violation of the Privacy Act”).

B. Procedural History

On March 24, 1999, the defendants filed a motion to dismiss pursuant to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 12(b)(1), (2), (3), and (6). On March 23, 2000, this court issued a Memorandum Opinion and supplemental order granting in part and denying in part the defendants’ motion to dismiss. M.K v. Tenet, 99 F.Supp.2d 12 (D.D.C.2000); Order dated Mar. 23, 2000. On April 20, 2001, the defendants filed a “motion for reconsideration” of that ruling pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 54(b), seeking to dismiss the plaintiffs’ remaining due process and Privacy Act claims. On November 30, 2001, the plaintiffs filed a motion for leave to file the second amended complaint along with the proposed second amended complaint. On December 3, 2001, this court issued a Memorandum Opinion and supplemental order granting in part and denying in part the defendants’ motion for reconsideration under Rule 54(b). M.K v. Tenet, 196 F.Supp.2d 8 (D.D.C.2001); Order dated Dec. 3, 2001. On December 4, 2001, this court set out the parties’ filing deadlines in its “Initial Scheduling and Procedures Order.” Order dated Dec. 4, 2001. On January 2, 2002, the defendants filed their instant motion to sever the claims of the six existing plaintiffs pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 21. On *137March 6, 2002, the plaintiffs filed a certificate of notification informing the CIA and the court of the 30 Doe defendants’ identities. For the reasons that follow, the court grants the plaintiffs’ motion to amend the complaint and denies the defendants’ motion to sever.

III. ANALYSIS

A. Legal Standard for a Motion to Amend

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 15(a) provides that a “party may amend the party’s pleading once as a matter of course at any time before a responsive pleading is served____” Fed. R. Civ. P. 15(a). Once a responsive pleading is filed, “a party may amend the party’s pleading only by leave of the court or by written consent of the adverse party; and leave shall be freely given when justice so requires.” Id.; see also Foman v. Davis, 371 U.S. 178, 182, 83 S.Ct. 227, 9 L.Ed.2d 222 (1962). The D.C. Circuit has held that for a trial court to deny leave to amend is an abuse of discretion unless the court provides a sufficiently compelling reason, such as “undue delay, bad faith, or dilatory motivef,] ... repeated failure to cure deficiencies by [previous] amendments [or] futility of amendment.” Firestone v. Firestone, 76 F.3d 1205, 1208 (D.C.Cir.1996) (quoting Foman, 371 U.S. at 182, 83 S.Ct. 227). The court may also deny leave to amend the complaint if it would cause undue prejudice to the opposing party. Foman, 371 U.S. at 182, 83 S.Ct. 227. In sum, a district court has wide discretion in granting leave to amend the complaint.

A court may deny a motion to amend the complaint as futile when the proposed complaint would not survive a Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss. James Madison Ltd. v. Ludwig, 82 F.3d 1085, 1099 (D.C.Cir.1996) (internal citations omitted). When a court denies a motion to amend a complaint, the court must base its ruling on a valid ground and provide an explanation. Id. “An amendment is futile if it merely restates the same facts as the original complaint in different terms, reasserts a claim on which the court previously ruled, fails to state a legal theory, or could not withstand a motion to dismiss.” 3 Moore’s Federal Practice § 15.15[3] (3d ed.2000).

B. Legal Standard for Severance

Claims against different parties can be severed for trial or other proceedings under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 20(b), 21, and 42(b). In re Vitamins Antitrust Litig., 2000 WL 1475705, at 16-17, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7397, at * 74 (D.D.C.2000) (Hogan, J.). Specifically, Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 21 governs the misjoinder of claims. Brereton v. Communications Satellite Corp., 116 F.R.D. 162 (D.D.C.1987) (Richey, J.) (holding that an appropriate remedy for mis-joinder is severance of claims brought by the improperly joined party). Rule 21 provides, in relevant part:

Misjoinder of parties is not ground for dismissal of an action. Parties may be dropped or added by order of the court on motion of any party or of its own initiative at any stage of the action and on such terms as are just. Any claim against a party may be severed and proceeded with separately.

Fed. R. Crv. P. 21. In determining whether the parties are misjoined, the joinder standard of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 20(a) applies. Rule 20(a) provides, in relevant part:

All persons may join in one action as plaintiffs if they assert any right to relief jointly, severally, or in the alternative in ■ respect of or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence or series of transactions or occurrences and if any question of law or fact common to all these persons will arise in the action.

The purpose of Rule 20 is to promote trial convenience and expedite the final resolution of disputes, thereby preventing multiple lawsuits, extra expense to the parties, and loss of time to the court as well as the litigants appearing before it. Anderson v. Francis I. duPont & Co., 291 F.Supp. 705, 711 (D.Minn.1968). The determination of a motion to sever is within the discretion of the trial court. In re Nat’l Student Marketing Litig., 1981 WL 1617, at *10 (D.D.C.1981) *138(Parker, J.); Bolling v. Mississippi Paper Co., 86 F.R.D. 6, 7 (N.D.Miss.1979).

There are two prerequisites for joinder under Rule 20(a): (1) a right to relief must be asserted by, or against, each plaintiff or defendant relating to or arising out of the same transaction or occurrence or series of transactions or occurrences, and (2) a question of law or fact common to all of the parties must arise in the action. Mosley v. Gen. Motors Corp., 497 F.2d 1330, 1333 (8th Cir.1974). “In ascertaining whether a particular factual situation constitutes a single transaction or occurrence for purposes of Rule 20, a case by case approach is generally pursued.” Id.

Additionally, “the court should consider whether an order under Rule 21 would prejudice any party, or would result in undue delay.” Id.; see also Brereton, 116 F.R.D. at 163 (stating that Rule 21 must be read in conjunction with Rule 42(b), which allows the court to sever claims in order to avoid prejudice to any party). The court may also consider whether severance will result in less jury confusion. Henderson v. AT & T Corp., 918 F.Supp. 1059, 1063 (S.D.Tex.1996) (directing in part that the claims of former employees from separate offices, which alleged various combinations of race, age, and national origin discrimination be severed because the claims were “highly individualized” and would be “extraordinarily confusing for the jury”); but see In re Vitamins Antitrust Litig., 2000 WL 1475705, at 17, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7397, at *75-76 (stating that courts “consistently deny motions to sever where [the] plaintiffs allege that [the] defendants have engaged in a common scheme or pattern of behavior” (citing Brereton, 116 F.R.D. at 164)).

C. The Court Grants the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Amend the Complaint

The plaintiffs ask this court for leave to file their second amended complaint in order “to address deficiencies found by the [c]ourt and to avail themselves of favorable intervening precedent,” referring to the D.C. Circuit’s decision in Jacobs v. Schiffer, 204 F.3d 259 (D.C.Cir.2000).4 Pis.’ Mot. at 2, 5. The plaintiffs state that the D.C. Circuit’s decision in Jacobs supports the plaintiffs’ claim that the defendants have violated the plaintiffs’ First Amendment rights by not allowing the plaintiffs to disclose to their attorneys government documents that are available to the plaintiffs.5 Jacobs, 204 F.3d *139at 261; Pis.’ Mot. at 5. Additionally, the plaintiffs seek to “address subsequent arguments raised by [the][d]efendants in their [m]otion for [reconsideration filed on April 20, 2001, and to add additional claims and [plaintiffs, all related through [the][d]efen-dants’ pattern and practice of obstruction of counsel.” Pis.’ Mot. at 2. Also, the plaintiffs seek to expand their allegations of the defendants’ violations of their right to effective assistance of counsel under the First Amendment to a “wide range of wrongful conduct,” as compared to the “plaintiffs’ initial allegations that the defendants merely refused to provide access to government documents.” Id. at 5.

The defendants challenge the plaintiffs’ proposed amendment asserting that the plaintiffs’ “factually diverse” claims are unrelated to each other. Defs.’ Opp’n at 1-2. Specifically, the defendants argue that “neither the existing six plaintiffs nor the proposed nine plaintiffs have alleged claims factually in common with one another.” Id. According to the defendants, the “wide range of wrongful conduct” that the plaintiffs allege in their proposed second amended complaint arises out of “unique sets of facts and circumstances, involving completely different types of [a]gency actions, proceedings or personnel matters, such as employment terminations, revocations of security clearances, forced resignations, disciplinary proceedings, failure to obtain promotions ... and retaliation.” Id. The plaintiffs’ proposed second amended complaint, however, cites to numerous obstruction-of-counsel situations, including denying counsel access to requested CIA policies, procedures, and documents upon request. 2d Am. Compl. 111124-27, 36-37, 64. Additionally, the plaintiffs allege that when they requested the presence of counsel, the defendants failed to accommodate that request and attempted to restrict the plaintiffs’ access to counsel. Id. HH59, 62, 65.

The defendants counter that they would suffer “undue prejudice” if the court grants the plaintiffs’ motion to amend. Defs.’ Opp’n at 6 (citing Atchinson v. District of Columbia, 73 F.3d 418, 425 (D.C.Cir.1996) (quoting Foman, 371 U.S. at 182, 83 S.Ct. 227)). The defendants further assert that the burden on the defendants “against fifteen substantially different sets of facts and legal arguments in one case far outweighs any practical benefit that might accrue from considering” the eases of the six existing plaintiffs and the nine new plaintiffs. Id.

1. The Plaintiffs Have Not Repeatedly Failed to Cure Deficiencies by Previous Amendments

The plaintiffs seek leave to amend their complaint to address prior deficiencies6 named by the court in its March 2000 Memorandum Opinion and to avail themselves of intervening legal precedent. Pis.’ Mot. at 5. As such, the court deems these justifications reasonable and concludes that the deficiencies that the plaintiffs seek to address are not “repeated failure[s] to cure deficiencies by amendments previously allowed.” Foman, 371 U.S. at 182, 83 S.Ct. 227.