16 Claim and Issue Preclusion - Res Judicata 16 Claim and Issue Preclusion - Res Judicata

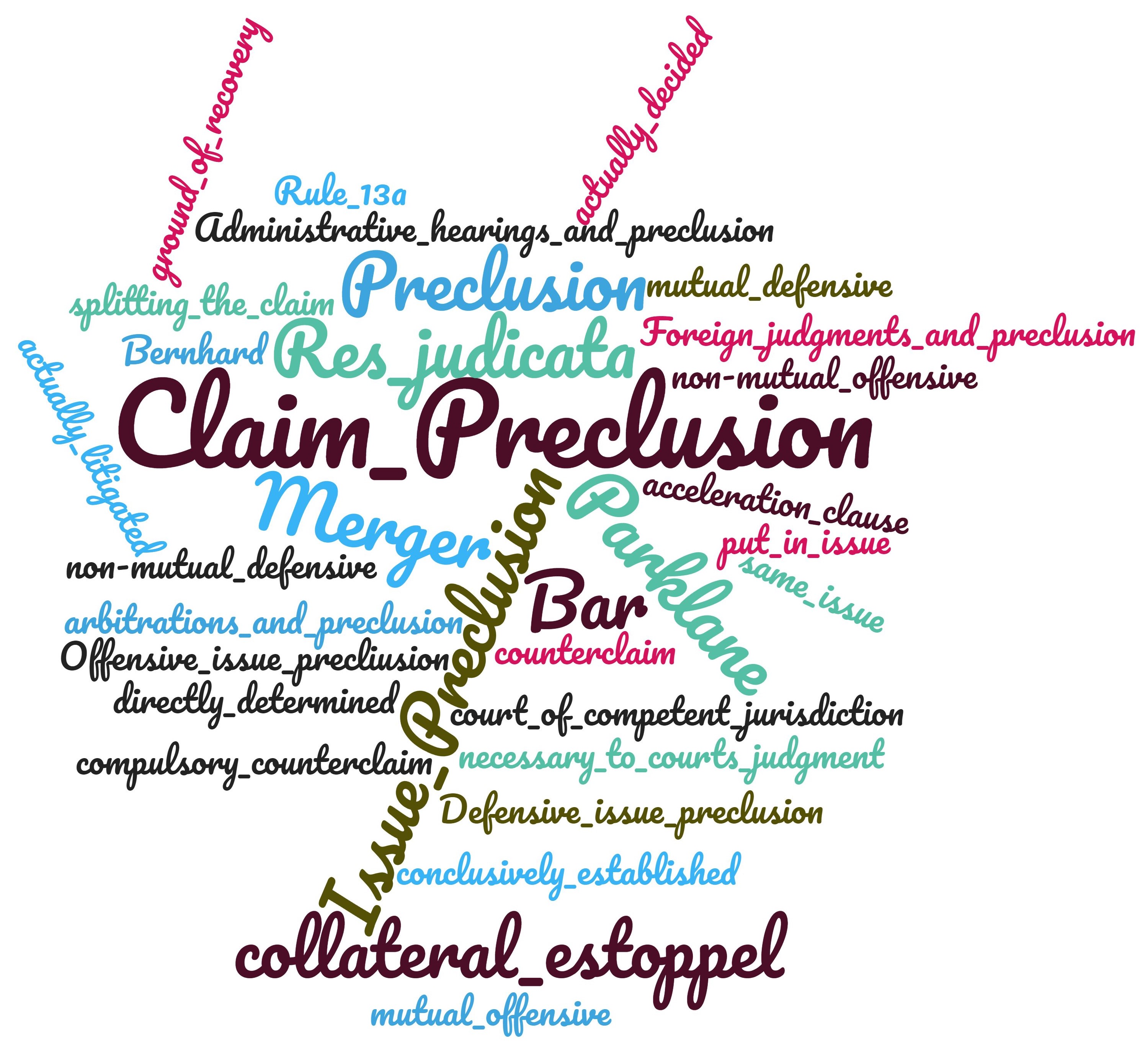

16.1 Preclusion Wordcloud 16.1 Preclusion Wordcloud

16.2 Introduction and Terminology 16.2 Introduction and Terminology

Claim and issue preclusion address principles that are easy to grasp in the abstract but sometimes difficult to apply. To make things a bit more complex, over the decades both the substance of the rules and the terminology used have shifted a bit.

Claim preclusion addresses the first concern of preclusion - that a party gets only one chance to bring a claim. Once a claim is won or lost, there cannot be a redo in hopes of doing better next time around. This involves both fairness to the parties, who are entitled to not be 'vexed' with duplicative litigation, but also institutional concerns as it is important to the authority of the courts that judgments have effect.

The meaning of 'claim' has shifted a bit over time. At one time, it was closely tied to the cause of action but today it usually involves more of an occurrence or transaction test. The modern application of claim preclusion precludes different causes of action so long as they are based on the same transaction or occurrence. As we shall see, bringing only some causes of action that might be brought can mean that the rest of them cannot be brought later.

The modern terminology is what we use in this course- claim preclusion. At one time, this same concept was referred to as res judicata (Latin for the thing has been decided), which is extra confusing because the term res judicata was also applied to the entire universe of preclusion, claim and issue preclusion combined.

There are more old terms tied to the concept. One old term and concept that has continued is forbidding "splitting the cause of action." This means that part of a claim cannot be brought in one suit, and the rest saved for another forum. When a party was victorious in the first suit, the doctrine of merger applies - the second attempt to bring the claim is merged into what was awarded the first time and cannot be brought separately. When the party was not victorious in the first suit, the doctrine of bar applies - the first loss bars the bringing of a second action. We will use the term claim preclusion rather than merger or bar, but you should recognize those terms as they often appear in older (and some new) cases.

Issue preclusion addresses the second concern of preclusion - once an issue is decided against a party, they are not allowed to relitigate it. Again, as we will see, the substance of this has shifted a bit. At one time, issue preclusion only applied if the parties were the same as in the first action or in privity with those in the first action. As we shall see, the potential use of issue preclusion is a bit broader now. Again, with regard to terminology, what we will call issue preclusion was once called collateral estoppel.

The third concern of preclusion is that before being precluded a party shall have had a "full and fair" chance to litigate the claim in a proper forum. As we shall see, there some details to sort out with regard to what constitutes a full and fair chance in a proper forum.

The fourth and final overriding concern of preclusion that we will address is that it must be asserted by the party seeking to benefit from it, and asserted sufficiently early in the litigation, to be applied. It's not one of those doctrines that can be invoked at any point of the litigation.

Note that in both claim preclusion and issue preclusion the question of whether the first court reached the correct result is not a concern. The policies at issue favor finality over accuracy.

16.3 Claim Preclusion 16.3 Claim Preclusion

16.3.1 Claim Preclusion Generally 16.3.1 Claim Preclusion Generally

At its most basic level, claim preclusion makes perfect sense: having litigated once to a fair and final resolution, a party should not be allowed to bring the same case again in hopes of a better result. Basic fairness and efficient administration of a judicial system argue for finality of result, which necessarily involves not allowing the parties to start with the same suit all over again.

As always, it’s not quite as simple as all that. What exactly do we mean by the ‘same case’ and what is required for us to conclude that the case was litigated to a fair and final resolution?

Courts require three conditions to be met before claim preclusion applies. First, the claim must be the same as what was litigated in the prior case. That requires that we define what we mean by the claim – are we looking only at the same cause of action or, in the old days, writ, or are we looking at something more akin to an occurrence or transaction test? Second, the first case must have been resolved by a final, valid judgment ‘on the merits.’ What exactly do we mean by that? Finally, in the area of claim preclusion, the parties must be sufficiently the same parties as those who litigated the first case.

The cases that follow will help illustrate how these issues play out.

16.3.2 Reeder v. Succession of Palmer 16.3.2 Reeder v. Succession of Palmer

This case was decided before the passage of 28 U.S.C. § 1367, which now governs supplemental jurisdiction. While we did not go deep into the cases that developed the doctrine of pendent jurisdiction, you will remember that before the adoption of § 1367 a line of cases developed the doctrine of pendent jurisdiction, which addressed essentially the same issue. We can see no reason why the shift to supplemental jurisdiction under § 1367 would change the court's analysis.

O. William REEDER v. The SUCCESSION OF Michael B. PALMER, Lynn Paul Martin, Individually and d/b/a LPM Enterprises and Bank of LaPlace.

Nos. 92-C-2965, 92-C-3002.

Supreme Court of Louisiana.

Sept. 3, 1993.

Rehearing Denied Oct. 7, 1993.

*1269Ellis B. Murov, Robert E. Kerrigan, John F. Willis, Deutsch, Kerrigan & Stiles, New Orleans, for applicant.

Stephen W. Rider, McGlinchey, Stafford, Cellini & Lang, New Orleans, Joseph Accar-do, Jr., Bruce A. North, Lynn P. Martin, Accardo, Edrington & Golden, La Place, for respondent.

The question before us is whether this state court action is barred by res judicata because of a prior federal court judgment in the defendants’ favor in a suit based on the same factual transaction or wrong as the *1270instant ease. Reeder sued for damages in federal court under federal securities statutes as the result of an alleged Ponzi or pyramid scheme perpetrated by Martin, Palmer, and others, and included a pendent state securities law claim (Reeder I). The federal district court dismissed Reeder’s case with prejudice for failure to state a claim on the ground that post-dated checks, issued to Reeder in return for his investments in a bogus air travel business, did not qualify as “securities” or “investment contracts” under federal or Louisiana securities law. Reeder v. Succession of Palmer, 736 F.Supp. 128 (E.D.La.1990). The federal court of appeal affirmed without opinion. Reeder v. Succession of Palmer, 917 F.2d 560 (5th Cir.1990).

Reeder then sued Martin and Palmer in a virtually identical action in state court, with the exceptions that his petition did not rely on federal statutes and included not only state securities claims, but also state contract, tort and unfair trade practices claims. (Reeder II). The state trial court sustained the defendants’ exceptions of res judicata and no cause of action, and dismissed Reed-er’s case with prejudice. The state court of appeal affirmed in part and reversed in part, holding that the federal court’s dismissal of the state securities -law claim operated as an adjudication on the merits for res judicata purposes, that the state tort claims had prescribed, that the state unfair trade practices claim was perempted, but that, although Reeder failed to state a cause of action in contract, his state law claim on this ground was not barred by res judicata and, therefore, he would be allowed an opportunity to amend his petition to remedy this deficiency. Reeder v. Succession of Palmer, 604 So.2d 1070 (La.App. 5th Cir.1992).

We reverse the court of appeal judgment in part and reinstate the trial court’s judgment dismissing Reeder’s state case with prejudice. The federal court had pendent jurisdiction over all of Reeder’s state law claims because they arose out of the same transaction or wrong as those presented in the federal proceeding. Therefore, Reeder was obligated to file in his first suit all the legal theories he wished to assert. The res judicata effect of the federal court judgment precludes the omitted state law claims because it is not clear that the federal district court would have declined to exercise pendent jurisdiction over them.

1. BACKGROUND

Dr. O. William Reeder filed a complaint in federal court alleging that Lynn Paul Martin, the late Michael B. Palmer, and others had defrauded him in violation of federal and Louisiana securities laws by operating an alleged Ponzi or pyramid scheme, (hereinafter Reeder I). Reeder’s complaint specifically requested that the federal district court exercise pendent jurisdiction over plaintiffs factually-related state securities law claim filed in the federal proceeding.

According to Reeder’s complaint, Palmer initially persuaded him in October of 1986 to invest in Martin’s “travel club” and thereafter acted as intermediary between him and Martin. Palmer and Martin allegedly solicited funds from individuals to purchase blocks of advance airline tickets for groups taking gambling trips to Las Vegas casinos, for which the casinos were to reimburse Martin and pay a commission. Martin purportedly promised to return all of the funds invested plus interest at the rate of 6% per month on the total invested. In reality, the “travel club” never engaged in legitimate business, and when the club repaid capital contributions and so-called dividends, the money was covertly taken from capital invested by other victims of the scheme. Reeder alleged that with each investment he received two post-dated checks drawn on Martin’s account with the Bank of LaPlaee; one check represented a return of principal, and the other represented a fixed interest payment. Reeder’s complaint stated that over the course of one and one-half years, he invested approximately $245,000 in Martin’s “travel club” and received only $68,000 in return, for a net loss of $185,000.

In April of 1988, Martin turned himself in to federal authorities and confessed to having operated a Ponzi scheme in violation of federal securities laws. Martin was indicted and pleaded guilty to federal criminal charges in connection with that scheme. See United States v. Lynn Paul Martin, No. 89-390 “C”(2) (E.D.La.). Because Palmer commit*1271ted suicide in May of 1988, his succession was named as a defendant in Reeder I.

In Reeder I, the federal district court concluded that no “securities” as defined under the federal or state securities laws were involved in Martin’s “travel club” scheme and dismissed Reeder’s case with prejudice. Reeder v. Succession of Palmer, 736 F.Supp. 128 (E.D.La.1990). The federal appellate court affirmed. Reeder v. Succession of Palmer, 917 F.2d 560 (5th Cir.1990). Reeder then activated a previously-filed state court suit against Martin and Palmer based on a petition virtually identical to his federal court action (Reeder II). Reeder sought damages based on factual allegations substantially the same as those in his federal complaint but grounded his suit in state securities law and other state law theories, rather than on federal statutes. The state trial court sustained the defendants’ exceptions of res judicata and no cause of action, and dismissed Reeder II with prejudice. The state court of appeal agreed that res judicata barred the state securities law claim, disposed of other claims on different grounds, but held that the contract claim was not barred by the federal court judgment. Reeder v. Succession of Palmer, 604 So.2d 1070 (La.App. 5th Cir.1990). We granted certiorari to determine whether the court of appeal correctly applied the principles of res judicata.

2. LAW AND ANALYSIS

When a state court is required to determine the preclusive effects of a judgment rendered by a federal court exercising federal question jurisdiction, it is the federal law of res judicata that must be applied. McNeal v. Paine, Webber, Jackson & Curtis, 249 Ga. 662, 293 S.E.2d 331 (1982); Anderson v. Phoenix Inv. Counsel of Boston, 387 Mass. 444, 440 N.E.2d 1164 (1982); Rennie v. Freeway Transport, 294 Or. 319, 656 P.2d 919 (1982); Jeanes v. Henderson, 688 S.W.2d 100 (Tex.1985), reh’g of cause overruled (May 1, 1985); Commercial Box & Lumber Co. v. Uniroyal, Inc., 623 F.2d 371, 373 (5th Cir.1980); Aerojet-General Corp. v. Askew, 511 F.2d 710 (5th Cir.), appeal dismissed and cert. denied, 423 U.S. 908, 96 S.Ct. 210, 46 L.Ed.2d 137 (1975); Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 87 (1982); C. Wright, A. Miller, & E. Cooper, Federal Practice and Procedure, Jurisdiction § 4468 (1981). Cf. Pilie & Pilie v. Metz, 547 So.2d 1305 (La.1989). Federal res judicata principles have been heavily influenced by the great advances in the Restatement Second of Judgments. Federal courts and commentators often cite and rarely depart from the Restatement view. 18 Wright, Miller & Cooper, Federal Practice and Procedure § 4401 (1981).

Under federal precepts, “claim preclusion” or “true res judicata” treats a judgment, once rendered, as the full measure of relief to be accorded between the same parties on the same “claim” or “cause of action.” When the plaintiff obtains a judgment in his favor, his claim “merges” in the judgment; he may seek no further relief on that claim in a separate action. Conversely, when a judgment is rendered for a defendant, the plaintiffs claim is extinguished; the judgment then acts as a “bar.” Under these rules of claim preclusion, the effect of a judgment extends to the litigation of all issues relevant to the same claim between the same parties, whether or not raised at trial. The aim of claim preclusion is thus to avoid multiple suits on identical entitlements or obligations between the same parties, accompanied, as they would be, by the redetermination of identical issues of duty and breach. Kaspar Wire Works, Inc. v. Leco Engineering & Mach., 575 F.2d 530 (5th Cir.1978) (Rubin, J., citing authorities). See Restatement (Second) of Judgments §§ 18-20 (1982).

Claim preclusion will therefore apply to bar a subsequent action on res judicata principles where parties or their privies have previously litigated the same claim to a valid final judgment. In most cases, the key question to be answered in adjudging the propriety of a claim preclusion defense is whether in fact the claim in the second action is “the same as,” or “identical to,” one upon which the parties have previously proceeded to judgment. The authorities do not provide a uniform definition of the terms “claim” or “cause of action” in connection with the application of res judicata. The clear trend, however, in the most recent decisions, in harmony with such procedural concepts as the *1272“transaction or occurrence” test for compulsory counterclaims as stated in Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 13(a) and the “common nucleus of operative fact” standard for pendent federal jurisdiction of United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715, 86 S.Ct. 1130, 16 L.Ed.2d 218 (1966), has been towards the adoption of § 24 of the Restatement 2d, of Judgments. That Section sets forth a “transactional analysis” as to what constitutes a “claim,” the extinguishment of which prohibits subsequent litigation with respect to the transaction(s) from which it arose. A majority of the federal circuit courts, as well as the Claims Court, have thus far expressly adopted the Restatement’s transactional approach. Annotation, Proper Test to Determine Identity of Claims for Purposes of Claim Preclusion by Res Judicata Under Federal Law, 82 A.L.R.Fed. 829, 837 (1987); e.g., Southmark Properties v. Charles House Corp., 742 F.2d 862 (5th Cir.1984). See Pilie & Pilie v. Metz, 547 So.2d 1305, 1310 (La.1989) (citing authorities).

Section 24 of the Restatement (Second) of Judgments (1982) adopts a “transactional” view of claim for purposes of the doctrines of merger and bar, as follows:

§ 24. Dimensions of “Claim” for Purposes of Merger or

Bar — General Rule Concerning “Splitting”

(1) When a valid and final judgment rendered in an action extinguishes the plaintiffs claim pursuant to the rules of merger or bar (see §§ 18, 19), the claim extinguished includes all rights of the plaintiff to remedies against the defendant with respect to all or any part of the transaction,- or series of connected transactions, out of which the action arose.

(2) What factual grouping constitutes a “transaction”, and what groupings constitute a “series”, are to be determined pragmatically, giving weight to such considerations as whether the facts are related in time, space, origin, or motivation, whether they form a convenient trial unit, and whether their treatment as a unit conforms to the parties’ expectations or business understanding or usage.

Illustrations of how the rule of § 24 applies to various situations are set forth in Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 25 (1982) as follows:

§ 25. Exemplifications of General Rule Concerning Splitting

The rule of § 24 applies to extinguish a claim by the plaintiff against the defendant even though the plaintiff is prepared in the second action

(1) To present evidence or grounds or theories of the case not presented in the first action, or

(2) To seek remedies or forms of relief not demanded in the first action.

Comment e of § 25 of the Restatement (Second) of Judgments (1982) explains the effects of the rules of §§ 24 and 25 in a case in which a given claim may be supported by theories or grounds arising from both state and federal law as follows:

A given claim may find support in theories or grounds arising from both state and federal law. When the plaintiff brings an action on the claim in a court, either state or federal, in which there is no jurisdictional obstacle to his advancing both theories or grounds, but he presents only one of them, and judgment is entered with respect to it, he may not maintain a second action in which he tenders the other theory or ground. If however, the court in the first action would clearly not have had jurisdiction to entertain the omitted theory or ground (or, having jurisdiction, would clearly have declined to exercise it as a matter of discretion), then a second action in a competent court presenting the omitted theory or ground should be held not precluded. * * *

See, e.g., Texas Employers’ Ins. Ass’n v. Jackson, 862 F.2d 491, 501 (5th Cir.1988); Langston v. Insurance Co. of North America, 827 F.2d 1044, 1046-47 (5th Cir.1987); Ocean Drilling & Explor. Co. v. Mont Boat Rental Serv., Inc., 799 F.2d 213, 216, 217 (5th Cir.1986) applying §§ 24 and 25 of Restatement (Second) of Judgments (1982).

Succinctly stated, if a set of facts gives rise to a claim based on both state and federal law, and the plaintiff brings the action in a federal court which had “pendent” jurisdiction to hear the state cause of action, *1273but the plaintiff fails or refuses to assert his state law claim, res judicata prevents him from subsequently asserting the state claim in a state court action, unless the federal court clearly would not have had jurisdiction to entertain the omitted state claim, or, having jurisdiction, clearly would have declined to exercise it as a matter of discretion. Restatement (Second) of Judgments §§ 24, 25 and 25, Comment e. E.g., Woods Exploration & Producing Co. v. Aluminum Co. of America, 438 F.2d 1286, 1315 (5th Cir.1971); Anderson v. Phoenix Inv. Counsel of Boston, 387 Mass. 444, 440 N.E.2d 1164, 1168 (1982). In cases of doubt, therefore, it is appropriate for the rules of res judicata to compel the plaintiff to bring forward his state theories in the federal action, in order to make it possible to resolve the entire controversy in a single lawsuit. Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 25, Reporter’s Note at 228; Woods Exploration & Producing Co. v. Aluminum Co. of America, 438 F.2d 1286, 1315 (5th Cir.1971). Applying these precepts to the case at hand, we conclude that each of the state law claims asserted by the plaintiff in Reeder II is precluded by the res judicata bar of the federal court judgment dismissing Reeder I with prejudice.

First, the present state law claims arise from the same set of facts or transaction as the federal and state securities law claims which the parties litigated to a valid final judgment on the merits in the federal court. The text and substance of the Ponzi scheme transaction or series of connected transactions alleged in the two actions are virtually the same, both involving the alleged intentional and/or negligent misrepresentations by Martin, Palmer and others to Reed-er and other investors disguising the true nature and operations of the alleged travel club pyramid scheme and the preeariousness of their investments.

Second, the federal district court had pendent jurisdiction to hear the state law claims which Reeder chose not to assert in that forum. Pendent jurisdiction, in the sense of judicial power, exists when there is a federal claim of “substance sufficient to confer subject matter jurisdiction on the court”, and the relationship between that claim and the state claim is such that they “derive from a common nucleus of operative fact”, so that “if, considered without regard to their federal or state character, a plaintiff[ ] ... would ordinarily be expected to try them all in one judicial proceeding....” United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715, 725, 86 S.Ct. 1130, 1138, 16 L.Ed.2d 218 (1966).

The requirement of substantiality does not refer to the value of the interests that are at stake but to whether there is any foundation of plausibility to the claim. Duke Power v. Carolina Environmental Study Group, Ind., 438 U.S. 59, 98 S.Ct. 2620, 57 L.Ed.2d 595 (1978); Garvin v. Rosenau, 455 F.2d 233 (6th Cir.1972). If the plaintiff raises a substantial federal question, the court has jurisdiction of the case and its decision must go to the merits of the case. A loose factual connection between the claims has been held enough to satisfy the requirements that they arise from a common nucleus of operative fact and that they be such that a plaintiff ordinarily would be expected to try them all in one judicial proceeding. Tower v. Moss, 625 F.2d 1161 (5th Cir.1980); Frye v. Pioneer Logging Machinery, Inc., 555 F.Supp. 730 (D.C.S.C.1983), citing Wright, Miller & Cooper, Federal Practice and Procedure. See id., § 3567.1 (1984). Therefore, it is clear that under these principles the federal court in Reeder I had pendent jurisdiction, in the sense of judicial power, over Reeder’s state law claims arising from the same transaction as his federal question claim. In fact, Reeder, by his own federal complaint, invoked the Reeder I court’s exercise of pendent jurisdiction over his state securities law claim.

Third, we cannot say that the federal district court in Reeder I “would clearly have declined to exercise” its pendent jurisdiction over the omitted state law tort, contract, unfair trade practice claims, and other state claims if Reeder had advanced them in that court along -with his state law securities act claim. Pendent jurisdiction is a doctrine of discretion which allows the trial court a wide latitude of choice in deciding whether to exercise that judicial power. See United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715, 725, 86 S.Ct. 1130, 1138, 16 L.Ed.2d 218 (1966). A federal *1274court must consider and weigh in each case, and at every stage of the litigation, the values of judicial economy, convenience, fairness, and comity in order to decide whether to exercise jurisdiction over a ease brought in that court involving pendent state law claims. When the balance of these factors indicates that a case properly belongs in state court, the federal court should decline the exercise of jurisdiction by dismissing the case without prejudice. The doctrine of pendent jurisdiction thus is a doctrine of flexibility, designed to allow courts to deal with cases involving pendent claims in the manner that most sensibly accommodates a range of concerns and values. Carnegie-Mellon Univ. v. Cohill, 484 U.S. 343, 108 S.Ct. 614, 98 L.Ed.2d 720 (1988); Rosado v. Wyman, 397 U.S. 397, 90 S.Ct. 1207, 25 L.Ed.2d 442 (1970); United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, supra.

In Gibbs, the Court stated that “if the federal claims are dismissed before trial ... the state claims should be dismissed as well.” 383 U.S. at 726, 86 S.Ct. at 1139. More recently, however, the Court has made clear that this statement does not establish a mandatory rule to be applied inflexibly in all cases. Jurisdiction is thus not automatically lost because the court ultimately concludes that the federal claim is without merit. See Carnegie-Mellon Univ. v. Cohill, 484 U.S. at 350, n. 7, 108 S.Ct. at 619 n. 7; Rosado v. Wyman, 397 U.S. at 403-405, 90 S.Ct. at 1213-1214. In fact, a countervailing policy in favor of hearing pendent state claims was expressed by the Court in Hagans v. Lavine, 415 U.S. 528, 94 S.Ct. 1372, 39 L.Ed.2d 577 (1974): “[I]t is evident from Gibbs that pendent state law claims are not always, or even almost always, to be dismissed and not adjudicated. On the contrary, given advantages of economy and convenience and no unfairness to litigants, Gibbs contemplates adjudication of these claims.” Id. at 545-546, 94 S.Ct. at 1383-1384.

The principles and standards of pendent jurisdiction support and mesh with the principles of res judicata. The plaintiff is required to bring forward his state theories in the federal action in order to make it possible to resolve the entire controversy in a single lawsuit. Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 25, Reporter’s Note at 228 (1982); Woods Exploration & Producing Co. v. Aluminum Co. of America, 438 F.2d at 1315. The federal district court, exercising its discretion, may decline jurisdiction of some or all of the plaintiffs state law claims if the court finds that the objectives of judicial economy, convenience and fairness to litigants, as well as other factors, will be served better thereby. United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. at 726, 86 S.Ct. at 1139. To insure that this decision will be made fairly and impartially by the court, rather than by a party seeking the tactical advantage of splitting claims, however, the claim preclusion rules further provide that, unless it is clear that the federal court would have declined as' a matter of discretion to exercise its pendent jurisdiction over state law claims omitted by a party, a subsequent state action on those claims is barred. Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 25, Comment e; Woods Exploration and Producing Co. v. Aluminum Co. of America, supra; Anderson v. Phoenix Inv. Counsel of Boston, 440 N.E.2d at 1169.

In view of the breadth of the federal trial courts’ discretion and the necessary indeterminacy of the discretionary standards, in order for a subsequent court to say that a federal district court clearly would have declined its jurisdiction of a claim not filed, the subsequent court must find that the previous case was an exceptional one which clearly and unmistakably required declination. The rules do not countenance a plaintiffs action in failing to plead a theory in a federal court with the hope of later litigating the theory in a state court as a second string to his bow. Therefore, the action on such omitted claims is barred if it is merely possible or probable that the federal court would have declined to exercise its pendent jurisdiction. Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 25, Comment e. See also Anderson v. Phoenix Inv. Counsel of Boston, 387 Mass. 444, 440 N.E.2d 1164, 1169 (1982).

Reeder I was not an exceptional case in which the federal court clearly or unmistakably would have declined to exercise its pendent jurisdiction over the related state law claims, had Reeder included them in his *1275complaint. In fact, the federal court did not decline to exercise its pendent jurisdiction over the only state law claim that it was asked to adjudicate, viz., Reeder’s claim for damages based on state securities law arising out of the same transaction or series of connected transactions as the state tort, contract, and unfair trade practices claims. Because the federal district court had exclusive jurisdiction of one of the federal securities law claims, 15 U.S.C. § 78aa, the federal court was the only forum in which it was possible to resolve the entire controversy in a single lawsuit. In these circumstances, the assertion of pendent jurisdiction is especially compelling. Cf., Aldinger v. Howard, 427 U.S. 1, 18, 96 S.Ct. 2413, 2422, 49 L.Ed.2d 276 (1976); Boudreaux v. Puckett, 611 F.2d 1028, 1031 (5th Cir.1978) (discussing pendent party jurisdiction where the federal court maintains exclusive jurisdiction over the underlying federal claim).

In a very similar case arising out of the same Ponzi scheme, the same federal district court did not decline pendent jurisdiction over state securities, fraud, and negligence law claims even after dismissing the federal securities law claim with prejudice for failure to state a claim. In fact, the federal district court considered and rendered final judgment on the merits on each of the pendent state law claims, ultimately dismissing each claim with prejudice. Guidry v. Bank of LaPlace, 740 F.Supp. 1208 (E.D.La.1990). On appeal, the Guidry court of appeal affirmed as to the dismissal of some of the state claims with prejudice, but required that some be dismissed without prejudice. Moreover, that court did not say that the federal district court clearly should have declined to exercise jurisdiction even as to the few pendent state law claims that were dismissed without prejudice. Guidry v. Bank of LaPlace, 954 F.2d 278 (5th Cir.1992). Therefore, in the present case, although it may have been possible for the district court to decline pendent jurisdiction of the omitted remaining state law claims, we cannot say that it was even probable, much less clear or unmistakable, that the federal court would have done so.

Our conclusion in this regard is bolstered by opinions of other courts which have held that, by the operation of federal res judicata principles, federal judgments under federal securities acts barred subsequent suit between the same parties deriving from a corn-mon nucleus of operative facts presenting state claims omitted from the earlier federal proceeding. See McNeal v. Paine, Webber, Jackson & Curtis, Inc., 249 Ga. 662, 293 S.E.2d 331 (1982) (federal judgment under Securities Exchange Act of 1934 barred negligence, breach of fiduciary duty, and fraud claims in state court); Anderson v. Phoenix Investment Counsel of Boston, Inc., 387 Mass. 444, 440 N.E.2d 1164 (1982) (federal judgment under Investment Advisers Act of 1940 barred unfair and deceptive trade practices claim in state court); Rennie v. Freeway Transport, 294 Or. 319, 656 P.2d 919 (1982) (federal judgment under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 barred fraud claim in state court); Jeanes v. Henderson, 688 S.W.2d 100 (Tex.), reh’g of cause overruled (May 1, 1985) (federal judgment under Securities Exchange Act of 1934 barred declaratory judgment action in state court). See also Browning Debenture Holders Comm. v. DASA Corp., 560 F.2d 1078 (2d Cir.1977) (prior final judgment based on federal securities laws barred litigation of pendent claims, even if the prior judgment did not explicitly rule on state law breach of fiduciary duty claims). In each of these cases, the state court could not find that it was clear, unmistakable or highly probable that the federal district court would have declined to exercise pendent jurisdiction over the factually-related state law claims. Thus, in each of the respective cases, federal res judicata barred the state claims later presented in state court.

DECREE

For these reasons, the judgment of the court of appeal affirming the trial court judgment sustaining the exception of res judicata as to the state securities claim is affirmed. The judgment of the court of appeal reversing the balance of the trial court’s judgment is vacated. The trial court’s judgment dismissing Reeder II, in its entirety, with prejudice is therefore reinstated.

AFFIRMED IN PART; REVERSED IN PART.

16.3.3 Jones v. Morris Plan Bank 16.3.3 Jones v. Morris Plan Bank

Wytheville

William B. Jones v. Morris Plan Bank of Portsmouth.

June 10, 1937.

Present, All the Justices.

*287The opinion states the case.

Thomas L. Woodward, for the plaintiff in error.

G. Curtis Hand, for the defendant in error.

delivered the opinion of the court.

William B. Jones instituted an action for damages against the Morris Plan Bank of Portsmouth for the conversion of his automobile. The parties will be designated here as they were in the trial court.

After the plaintiff had introduced all of his evidence and before the defendant had introduced any evidence on its behalf, the latter’s counsel moved to strike the evidence of the plaintiff and the court sustained the motion. A verdict for the defendant resulted.

The facts are that the plaintiff purchased from J. A. Parker, a dealer in automobiles, a Plymouth sedan, agreeing to pay therefor $595. He paid a part of the purchase price by the delivery of a used car to Parker of the agreed value of $245 and after crediting that amount on the purchase price and adding a finance charge of $78.40, there remained an unpaid balance due the dealer of $428. This latter *288amount was payable in 12 monthly installments of $35.70 each and evidenced by one note in the principal sum of $428.40. The note contained this provision: “The whole amount of this note (less any payments made hereon) becomes immediately due and payable in the event of nonpayment at maturity of any installment thereof.” The note was secured by the usual conditional sales contract used in like transactions, in which it was agreed that the title to the car would be retained by the dealer until the entire purchase price was paid in full. One of the provisions in the contract reads thus: “Said note or this contract may be negotiated or assigned or the payment thereof renewed or extended without passing title of said goods to purchaser.” Under this provision the contract was assigned to the defendant on the same day it was executed and the note was indorsed by Parker and delivered to the defendant at the same time.

Installment payments due on the note for May and June were not made when payable and for them an action was instituted in the Civil and Police Court of the city of Suffolk. No appearance was made by the defendant (Jones) in that action and judgment was obtained against him for the two payments. Execution issued upon the judgment and it was satisfied while in the hands of the sergeant of said city, by Jones, the plaintiff here, paying the full amount of the execution to the said sergeant.

Later the defendant instituted another action against Jones in the same court for the July installment which had become due and was unpaid, and to that action Jones filed a plea of res adjudicata, whereupon the defendant here (Morris Plan Bank of Portsmouth) took a non-suit.

On September 7, 1935, after the plaintiff had parked the automobile in the street in front of his home and had the key in his possession, the defendant, in the night time, through its agent, took possession of the automobile without the consent of the plaintiff and later sold it and applied the proceeds upon the note.

*289Afterwards, the plaintiff instituted the present action for conversion to recover damages for the loss of the automobile. His action in the court below was founded upon the theory that when the May and June installments became due and were unpaid, then under the acceleration clause in the note, the entire balance due thereon matured and at once became due and the defendant having elected to sue him for only two installments instead of the entire amount of the note, and having obtained a judgment for the two installments and satisfaction of the execution issued thereon, it waived its right to collect the balance. He also contends that the note was satisfied in the manner narrated and that the conditional sales contract, the sole purpose of which was to secure the payment of the note, served its purpose and ceased to exist, and, therefore, the title to the automobile was no longer retained, but upon the satisfaction of the note, passed to the plaintiff and was his property when the agent of the defendant removed it and converted it to its own use.

The position of the defendant is that in an action for conversion it is essential that the plaintiff establish his ownership of the property at the time of the conversion. It asserts that the title to the automobile, which was the subject of the alleged conversion, was not vested in the plaintiff at the time of the action, nor since, because the condition in the contract was that the title should be retained by the seller (whose rights were assigned to the defendant) until the entire purchase price was paid, and that the purchase price had never been paid, and, therefore, the plaintiff has never had title to the automobile and could not maintain the action of conversion.

The defendant also contends that the note and conditional sales contract were divisible; that successive actions could be brought upon the installments as they matured, and that it was not bound, at the risk of waiving its right to claim the balance, to sue for all installments in one action.

The defendant does not deny that the acceleration clause *290matured all installments upon the default in the payment of the May and June payments.

This court has definitely recognized and upheld a provision in a note accelerating its maturity on non-payment of interest or installments. Nickels v. People’s Building, Loan & Saving Association, 93 Va. 380, 382, 25 S. E. 8; Fant v. Thomas, 131 Va. 38, 108 S. E. 847, 19 A. L. R. 280; Country Club v. Wilkins, 166 Va. 325, 186 S. E. 23, 24.

We decide that under the unconditional acceleration provision in the note involved here and in the absence of the usual optional provision reserved to the holder, the entire amount due upon the note became due and payable when default was made in paying an installment. Therefore, when the action before the Civil and Police Justice of Suffolk was instituted, all the installments were due and payable.

Was it essential that the defendant here institute an action for all of the installments then due, or could it institute its action for only two of the installments and later institute another action for other installments? The answer to that question depends upon the nature of the transaction. If a transaction is represented by one single and indivisible contract and the breach gives rise to one single cause of action, it cannot be split into distinct parts and separate actions maintained for each.

On the other hand if the contract is divisible, giving rise to more than one cause of action each may be proceeded upon separately.

Was the contract here single and indivisible or was it divisible? Our answer is that the note and conditional sales contract constituted one single contract. The sole purpose of the conditional sales contract was to retain the title in the seller until the note was paid. When that condition was performed, the contract ended.

One of the principal tests in determining whether a demand is single and entire, or whether it is several, so as to give rise to more than one cause of action, is the identity of *291facts necessary to maintain the action. If the same evidence will support both actions there is but one cause of action.

In the case at bar, all of the installments were due. The evidence essential to support the action on the two installments for which the action was brought would be the identical evidence necessary to maintain an action upon all of the installments. All installments having matured at the time the action was begun, under well settled principles, those not embraced in that action are now barred.

The well established rule forbidding the splitting of causes of action is clearly stated in 1 Am. Jur., “Actions,” §96. It is there said: “One may bring separate suits on separate causes of action even if joinder of the separate causes in one action is permissible, subject, however, to the power of the court to order consolidation. On the other hand, one who has a claim against another may take a part in the satisfaction of the whole, or maintain an action for a part only, of the claim, although there is some authority to the effect that a part of a demand cannot be waived for the purpose of giving an inferior court jurisdiction. ' But after having brought suit for a part of a claim, the plaintiff is barred from bringing another suit for another part. The law does not permit the owner of a single or entire cause of action or an entire or indivisible demand, without the consent of the person against whom the cause or demand exists to divide or split that cause or demand so as to make it the subject of several actions. The whole cause must be determined in one action. If suit is brought for a part of a claim, a judgment obtained in that action precludes the plaintiff from bringing a second action for the residue of the claim, notwithstanding the second form of action is not identical with the first, or different grounds for relief are set forth in the second suit. This principle not only embraces what was actually determined, but also extends to every other matter which the parties might have litigated in the case. The rule is founded upon the plainest and most substantial justice, namely, that litigation should have an *292end and that no person should be unnecessarily,harassed with a multiplicity of suits.”

In the same work, under the same title, § 107, we find the following: “A contract to pay money in installments is divisible in its nature. Hence, each default in the payment of an installment may be the subject of an independent action provided it is brought before the next instalment becomes due, generally speaking, however, a recovery for one installment will bar an action for the recovery of other installments then due. In other words, each action should include every installment due at the time it is commenced, unless a suit is, at the time, pending for the recovery thereof, or other special circumstances exist.”

In I Corpus Juris Secundum, “Actions,” § 102, page 1308, it is said: “The object of the rule against splitting causes of action is to prevent a multiplicity of suits. The law does not favor such a multiplicity; instead it favors any action that will prevent other actions involving the same transaction. The rule exists mainly for the protection of defendant, is intended to suppress serious grievances, and is applied to prevent vexatious litigation and to avoid the costs and expenses incident to numerous suits on the same cause of action. It is based on the maxims, Interest reipublicae ut sit finis litium (It concerns the commonwealth that there be a limit to litigation), and Nemo debet bis vexari pro una et eadem causa (No one ought to be twice vexed for one and the same cause).”

Again in the same work and volume at page 1309 the nature of the rule is said to be: “The rule against splitting causes of action is based on principles of public policy. It is a salutary principle. It is a rule of justice, not to be classed among technicalities, and is not altogether a rule of original legal right, but is rather an equitable interposition of the courts to prevent a multiplicity of suits through reasons of public policy. As a defense it is not an estoppel, but a bar.”

See also, Kennedy v. New York, 196 N. Y. 19, 89 N. E. 360, 25 L. R. A. (N. S.) 847; Matheny v. Preston Hotel *293Co., 140 Tenn. 41, 203 S. E. 327; Stroud v. Conine, 114 Ark. 304, 169 S. W. 959.

The general rule established in Virginia is the same as that prevailing in the majority of jurisdictions. See Digest of Virginia and West Virginia Reports, vol. 1, page 79; Hite v. Long, 6 Rand. 457, 18 Am. Dec. 719; Huff v. Broyles, 26 Gratt. (67 Va.) 283, 285; St. Lawrence Boom & Manufacturing Co. v. Price, 49 W. Va. 432, 38 S. E. 526; Hamilton v. Goodridge, 164 Va. 123, 178 S. E. 874.

In Hancock v. White Hall Tobacco Warehouse Co., 102 Va. 239, 46 S. E. 288, it was held that “A demand arising from an entire contract cannot be divided and made the subject of several suits; and if several suits are brought for a breach of such a contract, a judgment upon the merits in either will bar a recovery in the others.”

Our conclusion is that the court below erroneously struck the evidence of the plaintiff, because when the defendant instituted its action for only two of the installments (when all of the others were due), obtained a judgment on them and procured satisfaction of the execution issued thereon, it constituted a complete bar to any action for the other installments; therefore, the appellant is not allowed to set up, in defense of the present action for the conversion of the automobile, the fact that other installments have not been paid though they were due when the first action was instituted. At the time the defendant lost its right to institute any action for the remaining installments, the title to the automobile passed to the plaintiff. He was the owner at the time the agent of the defendant took possession of it and exposed it to sale.

It follows that the judgment of the court below will be reversed, and the case will be remanded for the sole purpose of determining the quantum of damages.

Reversed and remanded.

16.3.4 Claim Preclusion Reviewed 16.3.4 Claim Preclusion Reviewed

Nature of a Claim. Both of the cases we read address the nature of a claim. What are the boundaries of a claim? Older cases looked to the boundaries of a 'claim' in terms of the cause of action pursued, looking to whether the same facts would be needed to prove the new causes of action being advanced in a separate action or whether allowing the new case would conflict with the result in the first case. More modern approaches take a broader transactional approach. The Restatement of the Law of Judgments 2d defines it this way in Section 24:

(1) When a valid and final judgment rendered in an action extinguishes the plaintiff's claim pursuant to the rules of merger or bar (see §§ 18, 19), the claim extinguished includes all rights of the plaintiff to remedies against the defendant with respect to all or any part of the transaction, or series of connected transactions, out of which the action arose.

(2) What factual grouping constitutes a “transaction”, and what groupings constitute a “series”, are to be determined pragmatically, giving weight to such considerations as whether the facts are related in time, space, origin, or motivation, whether they form a convenient trial unit, and whether their treatment as a unit conforms to the parties' expectations or business understanding or usage.

As noted in the Reeder v. Succession of Palmer case, this approach is followed in the federal courts and in many state courts. The net of it is that when a judgment is issued by a federal court on a federal question claim, causes of action arising from the same transaction or occurrence that might have been brought and that were not brought are barred.

Defenses and Mandatory Counterclaims. Claim preclusion can also arise when a defense is asserted or a counterclaim is not brought. For example, in Mitchell v. Federal Intermediate Credit Bank, 165 S.C. 457, 164 S.E. 136 (1932), a farmer borrowed $9,000 from a bank to buy seed potatoes. When the potatoes were harvested, the farmer delivered them to an agent of the bank, who sold them for $18,000. The agent, however, embezzled the proceeds and did not deliver them to the bank. The bank sued the farmer for the $9,000. As a defense, the farmer asserted that he had delivered the potatoes and claimed the bank's claim should be offset by the proceeds. The farmer did not, however, assert a counterclaim for the remaining $9,000. The court held for the farmer on the defense. The farmer later brought a separate action for the remaining $9,000. The court held that the farmer lost his claim by not asserting it as a counterclaim in the first action:

The transaction out of which the case at bar arises is the same transaction that Mitchell pleaded as a defense in the federal suit. He might, therefore, "have recovered in that action, upon the same allegations and proofs which he there made, the judgment which he now seeks if he had prayed for it." He did not do this, but attempted to split his cause of action, and to use one portion of it for defense in that suit and to preserve the remainder for offense in a subsequent suit, which, under applicable principles, could not be done.

The Mitchell case predated the federal rules, but the same result would be dictated today by the mandatory counterclaim rule.

Valid, Final, and On the Merits. The standard language for application of preclusion is that the first judgment has to be valid, final, and on the merits. Validity you should have a sense of based on our study of personal jurisdiction and notice. If the court does not have the power to bind a party, the judgment is not valid. Remember, however, that if in the first action the defendant appeared and contested personal jurisdiction, it will not be attackable collaterally. What about if there was no subject matter jurisdiction? This turns out to be a bit slipperier, but in general if the judgment is final and the court found it had subject matter jurisdiction, as it always should do in federal court, the validity of subject matter jurisdiction will not be reopened.

Finality is also a bit slippery. Finality requires that the trial phase of the case be final, with nothing more to do than execute the judgment, or a test similar to the finality rule with regard to appeals. Interestingly, finality does not depend upon the resolution of all appeals. While a court may stay its decision on whether to apply claim preclusion while a case is on appeal, it also can apply claim conclusion when the trial phase is final but the appeal is pending.

On the merits is the trickiest of all. The paradigm cases at either end are quite clear. There are a number of reasons that a court might find it is unable to hear the case - lack of personal jurisdiction, subject matter jurisdiction, venue, or improper notice, to name some. In those cases, the resolution will be on procedural grounds, and not on the merits, and claim preclusion will not apply. The plaintiff will be free to refile elsewhere. The other extreme is equally clear. If the plaintiff has received a full trial on the merits, and the facts are found against her, the resolution is on the merits, and claim preclusion applies. There are, however, a range of settings where the preclusive effect of judgments can be unclear. A dismissal for failure to state a claim under Rule 12(b)(6) may or may not have preclusive effects depending on the pleading rules and the opportunity (or not) to replead. A voluntary dismissal, although with prejudice in the court where it was rendered, may or may not have preclusive effect elsewhere. And so on. For our purposes, limited in time as we are, recognizing the clarity of the outer boundaries and the indeterminacy of special situations is as far as we have time to go.

Identity of the Parties. The transaction test for claims allows claim preclusion to bar causes of action that might have been brought but that weren't, but what about parties? Are claims barred against parties who might have been joined but were not? No. Claim preclusion only applies when the parties are the same.

Acceleration Clauses. Acceleration clauses are routinely used in modern debt contracts. If a debtor falls behind on a contract, the lender wants to be free to bring the issue to a head and seek immediate payment of the entire debt. This can give a lender significant leverage over a borrower who had counted on a long period of time to repay the loan but is late on one payment.

Without an acceleration clause, claim preclusion will not apply to payments that are not yet due. The plaintiff has no right to those claims until the time for the payment arrives. In the absence of an acceleration clause, the plaintiff has to bring the claims in series as payments become due.

If there is an acceleration clause, however, all payments become due at once, and are barred by claim preclusion if not sought in the first action. This was the lesson learned by the bank in the Jones case.

16.4 Issue Preclusion 16.4 Issue Preclusion

16.4.1 Issue Preclusion Generally 16.4.1 Issue Preclusion Generally

When can factual and legal determinations made in one case be used in another case? That is what is at stake when we address issue preclusion.

The historical standard for issue preclusion was expressed as follows:

The general principle announced in numerous cases is that a right, question or fact distinctly put in issue and directly determined by a court of competent jurisdiction, as a ground of recovery, cannot be disputed in a subsequent suit between the same parties or their privies; and even if the second suit is for a different cause of action, the right, question or fact once so determined must, as between the same parties or their privies, be taken as conclusively established, so long as the judgment in the first suit remains unmodified. This general rule is demanded by the very object for which civil courts have been established, which is to secure the peace and repose of society by the settlement of matters capable of judicial determination. Its enforcement is essential to the maintenance of social order; for, the aid of judicial tribunals would not be invoked for the vindication of rights of person and property, if, as between parties and their privies, conclusiveness did not attend the judgments of such tribunals in respect of all matters properly put in issue and actually determined by them.

Harlan, J., in Southern Pacific Railroad Co. v. United States

Note the elements included in Justice Harlan's formulation:

- The issue must be the same. This can involve not just the boundaries of the issue but also whether the standard of proof in the first action is as high as in the second action or if the evidence needed to prove an issue has changed since the first action.

- The issue must have been 'distinctly put in issue' or as it is often phrased 'actually litigated' - that is, rather than being a potential issue it must be one that the parties actually put in active dispute. This element means that default judgments, while having claim preclusion effect if valid, will not have issue preclusion effect.

- The issue must be 'directly determined' which is to say 'actually decided' by the court. An issue not determined by the first court will not be given issue preclusion effect.

- The issue must be 'a ground of recovery' or as is sometimes put 'necessarily decided.' Statements in dicta, for example, do not give rise to issue preclusion.

There are some other limitations on issue preclusion. If the first court was of limited jurisdiction, that might prevent the application of issue preclusion. For example, in the US state small claims courts are often limited to claims of relatively low dollar value - below $10,000 or even below $1,000. If the second claim is for $1,000,000, the second court will not give preclusive effect to the findings of the small claim court.

You will not be surprised to learn that for each of the elements of issue preclusion complicating issues can arise. You will also not be surprised to learn that courts faced with the complicating issues did not all decide them the same way. To unpack the issues involved and the alternate paths would take time. For our purposes, with time limited, we will not explore the frontiers of the doctrine.

The rule stated by Justice Harlan remains correct but not complete. In the following cases we will explore the degree to which the second dispute has to be between the same parties or their privies.

16.4.2 Rios v. Davis 16.4.2 Rios v. Davis

At the time this case was decided, a finding of contributory negligence on the part of the plaintiff was sufficient to prevent the plaintiff from recovering. You will see how that matters to the case.

Juan C. RIOS, Appellant, v. Jessie Hubert DAVIS, Appellee.

No. 3847.

Court of Civil Appeals of Texas. Eastland.

Nov. 22, 1963.

Rehearing Denied Dec. 20, 1963.

*387Potash, Cameron, Bernat & Studdard, Brewster & Hoy, El Paso, for appellant.

Scott, Hulse, Marshall & Feuille, El Paso, for appellee.

Juan C. Rios brought this suit against Jessie Hubert Davis in the District Court to recover damages in the sum of $17,500.-00, alleged to have been sustained as a result of personal injuries received on December 24, 1960, in an automobile collision. Plaintiff alleged that his injuries were proximately caused by negligence on the part of the defendant. The defendant answered alleging that Rios was guilty of contributory negligence. Also, among other defenses, the defendant urged a plea of res judicata and collateral estoppel based upon the findings and the judgment entered on December 17, 1962, in a suit between the same parties in the County Court at Law of El Paso County. The plea of res judicata was sustained and judgment was entered in favor of the defendant Jessie Hubert Davis. Juan C. Rios has appealed.

It is shown by the record that on April 11, 1961, Popular Dry Goods Company brought suit against appellee Davis in the El Paso County Court at Law, seeking to recover for damages to its truck in the sum of $443.97, alleged to have been sustained in the same collision here involved. Davis answered alleging contributory negligence on the part of Popular and joined appellant Juan C. Rios as a third party defendant and sought to recover from Rios $248.50, the alleged amount of damages to his automobile. The jury in the County Court at Law found that Popular Dry Goods Company and Rios were guilty of negligence proximately causing the collision. However, the jury also found that Davis was guilty of negligence proximately causing the collision, and judgment was entered in the County Court at Law denying Popular Dry Goods any recovery against Davis and denying Davis any recovery against Rios.

Appellant Rios in his third point contends that the District Court erred in sustaining appellee’s plea of res judicata based upon the judgment of the County Court at Law because the findings on the issues regarding appellant’s negligence and liability in the County Court at Law case were immaterial because the judgment entered in that case was in favor of appellant. We sustain this point. We are unable to agree with appellee’s contention that the findings in the County Court at Law case that Rios was guilty of negligence in failing to keep a proper lookout and in driving on the left side of the roadway, and that such negligent acts were proximate causes of the accident were essential to the judgment entered therein. The sole basis for the judgment in the County Court at Law as between Rios and Davis was the findings concerning the negligence of Davis. The finding that Rios was negligent was not essential or material to the judgment and the judgment was not based thereon. On the contrary, the finding in the County Court at Law case that Rios was negligent proximately causing the accident would, if it had been controlling, led to a different result. Since the judgment was in favor *388of Rios he had no right or opportunity to complain of or to appeal from the finding that he was guilty of such negligence even if such finding had been without any support whatever in the evidence. The right of appeal is from a judgment and not from a finding. The principles controlling the fact situation here involved are, in our opinion, stated in the following quoted authorities and cases. The annotation in 133 A.L.R. 840, page 850 states:

“According to the weight of authority, a finding of a particular fact is not res judicata in a subsequent action, where the finding not only was not essential to support the judgment, but was found in favor of the party against whom the judgment was rendered, and, if allowed to control, would have led to a result different from that actually reached.”

In the case of Word v. Colley, Tex.Civ. App., 173 S.W. 629, at page 634 of its opinion (Error Ref.), the court stated as follows:

“It is the judgment, and not the verdict or the conclusions of fact, filed by a trial court which constitutes the es-toppel, and a finding of fact by a jury or a court which does not become the basis or one of the grounds of the judgment rendered is not conclusive against either party to the suit.”

In 2 Black on Judgments, p. 609, the author states the rule of estoppel by judgment as follows:

“ ‘The force of the estoppel resides in the judgment. It is not the finding of the court or the verdict of the jury rendered in an action which concludes the parties in subsequent litigation, but the judgment entered thereon.’

“The fact that the judgment in the suit in Cherokee county was in favor of defendants precluded them from bringing in review the findings of the judge, and we cannot believe that a party can be estopped by a judgment in his favor from denying findings of the court rendering said judgment the decision of which was not essential or material to the rendition of the judgment. Philipowski v. Spencer, 63 Tex. 607; Sheffield v. Goff, 65 Tex. 358; Manning v. Green, 56 Tex.Civ. App. 579, 121 S.W. 725; Whitney v. Bayer, 101 Mich. 151, 59 N.W. 415; Cauhape v. Parke, Davis & Co., 121 N.Y. 152, 24 N.E. 186; 23 Cyc. 1227, 1228.”

The above quotation is quoted with approval by the Supreme Court of Texas in Permian Oil Company v. Smith, 129 Tex. 413, 73 S.W.2d 490 at page 500. See also Rushing v. Mayfield Company, Tex. Civ.App., 104 S.W.2d 619; Cambria v. Jeffery, 307 Mass. 49, 29 N.E.2d 555; Karameros v. Luther, 279 N.Y. 87, 17 N.E.2d 779.

We cannot agree with appellee’s contention that Rio Bravo Oil Company v. Hebert, 130 Tex. 1, 106 S.W.2d 242, is contrary to and requires an adverse determination of appellant’s third point. The language particularly relied upon by appellant in that case was as follows:

“Although the judgment of the court was, as we formerly held, only a denial of the right to recover the particular land there in controversy, its estoppel is much broader, and concludes the parties upon every question which was directly in issue, and was passed upon by the court in arriving at its judgment. * * * ”

“ * * * But, where the second action between the same parties is upon a different claim or demand, the judgment in the prior action operates as an estoppel only as to those matters in issue or points controverted, upon the determination of which the finding or verdict was rendered.”

*389For the reasons stated the court erred in entering judgment for Jessie Hubert Davis based upon his plea of res judicata and collateral estoppel. The judgment is, therefore, reversed and the cause is remanded.

16.4.3 Bernhard v. Bank of America 16.4.3 Bernhard v. Bank of America

HELEN BERNHARD, as Administratrix, etc., Appellant,

v.

BANK OF AMERICA NATIONAL TRUST & SAVINGS ASSOCIATION (a National Banking Association), Respondent.

Supreme Court of California. In Bank.

Joseph Brenner for Appellant.

Louis Ferrari, Edmund Nelson and G. L. Berrey for Respondent.

TRAYNOR, J.

In June, 1933, Mrs. Clara Sather, an elderly woman, made her home with Mr. and Mrs. Charles [809] O. Cook in San Dimas, California. Because of her failing health, she authorized Mr. Cook and Dr. Joseph Zeiler to make drafts jointly against her commercial account in the Security First National Bank of Los Angeles. On August 24, 1933, Mr. Cook opened a commercial account at the First National Bank of San Dimas in the name of "Clara Sather by Charles O. Cook." No authorization for this account was ever given to the bank by Mrs. Sather. Thereafter, a number of checks drawn by Cook and Zeiler on Mrs. Sather's commercial account in Los Angeles were deposited in the San Dimas account and checks were drawn upon that account signed "Clara Sather by Charles O. Cook" to meet various expenses of Mrs. Sather.

On October 26, 1933, a teller from the Los Angeles Bank called on Mrs. Sather at her request to assist in transferring her money from the Los Angeles Bank to the San Dimas Bank. In the presence of this teller, the cashier of the San Dimas Bank, Mr. Cook, and her physician, Mrs. Sather signed by mark an authorization directing the Security First National Bank of Los Angeles to transfer the balance of her savings account in the amount of $4,155.68 to the First National Bank of San Dimas. She also signed an order for this amount on the Security First National Bank of San Dimas "for credit to the account of Mrs. Clara Sather." The order was credited by the San Dimas Bank to the account of "Clara Sather by Charles O. Cook." Cook withdrew the entire balance from that account and opened a new account in the same bank in the name of himself and his wife. He subsequently withdrew the funds from this last mentioned account and deposited them in a Los Angeles Bank in the names of himself and his wife.

Mrs. Sather died in November, 1933. Cook qualified as executor of the estate and proceeded with its administration. After a lapse of several years he filed an account at the instance of the probate court accompanied by his resignation. The account made no mention of the money transferred by Mrs. Sather to the San Dimas Bank; and Helen Bernhard, Beaulah Bernhard, Hester Burton, and Iva LeDoux, beneficiaries under Mrs. Sather's will, filed objections to the account for this reason. After a hearing on the objections the court settled the account, and as part of its order declared that [810] the decedent during her lifetime had made a gift to Charles O. Cook of the amount of the deposit in question.

After Cook's discharge, Helen Bernhard was appointed administratrix with the will annexed. She instituted this action against defendant, the Bank of America, successor to the San Dimas Bank, seeking to recover the deposit on the ground that the bank was indebted to the estate for this amount because Mrs. Sather never authorized its withdrawal. In addition to a general denial, defendant pleaded two affirmative defenses: (1) that the money on deposit was paid out to Charles O. Cook with the consent of Mrs. Sather and (2) that this fact is res judicata by virtue of the finding of the probate court in the proceeding to settle Cook's account that Mrs. Sather made a gift of the money in question to Charles O. Cook and "owned no sums of money whatsoever" at the time of her death. Plaintiff demurred to both these defenses, and objected to the introduction in evidence of the record of the earlier proceeding to support the plea of res judicata. She also contended that the probate court had no jurisdiction to pass upon. Cook's ownership of the money because the executor resigned before the filing of the objections. This last contention was answered before judgment was entered, by the decision of this court in Waterland v. Superior Court, 15 Cal.2d 34 [98 PaCal.2d 211], holding that the probate court has jurisdiction in such a situation. The trial court overruled the demurrers and objection to the evidence, and gave judgment for defendant on the ground that Cook's ownership of the money was conclusively established by the finding of the probate court. Plaintiff has appealed, denying that the doctrine of res judicata is applicable to the instant case or that there was a valid gift of the money to Cook by Mrs. Sather.

Plaintiff contends that the doctrine of res judicata does not apply because the defendant who is asserting the plea was not a party to the previous action nor in privity with a party to that action and because there is no mutuality of estoppel.

The doctrine of res judicata precludes parties or their privies from relitigating a cause of action that has been finally determined by a court of competent jurisdiction. Any issue necessarily decided in such litigation is conclusively determined as to the parties or their privies if it is involved in a subsequent lawsuit on a different cause of action. (See cases cited in 2 Freeman, Judgments (5th ed.) sec. 627; 2 Black, [811] Judgments (2d ed.), sec. 504; 34 C.J. 742 et seq.; 15 Cal.Jur. 97.) The rule is based upon the sound public policy of limiting litigation by preventing a party who has had one fair trial on an issue from again drawing it into controversy. (See cases cited in 38 Yale L. J. 299; 2 Freeman, Judgments (5th ed.), sec. 626; 15 Cal.Jur. 98.) The doctrine also serves to protect persons from being twice vexed for the same cause. (Ibid) It must, however, conform to the mandate of due process of law that no person be deprived of personal or property rights by a judgment without notice and an opportunity to be heard. (Coca Cola Co. v. Pepsi Cola Co., 36 Del. 124 [172 Atl. 260]. See cases cited in 24 Am. and Eng. Encyc. (2d ed.), 731; 15 Cinn. L. Rev. 349, 351; 82 Pa. L. Rev. 871, 872.)

Many courts have stated the facile formula that the plea of res judicata is available only when there is privity and mutuality of estoppel. (See cases cited in 2 Black, Judgments (2d. ed.), secs. 534, 548, 549; 1 Freeman, Judgments (5th ed.), secs. 407, 428; 35 Yale L. J. 607, 608; 34 C.J. 973, 988.) Under the requirement of privity, only parties to the former judgment or their privies may take advantage of or be bound by it. (Ibid) A party in this connection is one who is "directly interested in the subject matter, and had a right to make defense, or to control the proceeding, and to appeal from the judgment." (1 Greenleaf, Evidence (15th ed.), sec. 523. See cases cited in 2 Black, Judgments (2d ed.), sec. 534; 15 R. C. L. 1009 [134]; 9 Va. L. Reg. (N.S.) 241, 242; 15 Cal.Jur. 190; 34 C.J. 992.) A privy is one who, after rendition of the judgment, has acquired an interest in the subject matter affected by the judgment through or under one of the parties, as by inheritance, succession, or purchase. (See cases cited in 2 Black, Judgments (2d ed.), sec. 549; 35 Yale L. J. 607, 608; 34 C.J. 973, 1010, 1012; 15 R. C. L. 1016. [135]) The estoppel is mutual if the one taking advantage of the earlier adjudication would have been bound by it, had it gone against him. (See cases cited in 2 Black, Judgments (2d ed.), sec. 534, 548; 1 Freeman, Judgments (5th ed.), sec. 428; 35 Yale L. J. 607, 608; 34 C.J. 988; 15 R. C. L. 956. [136])

The criteria for determining who may assert a plea of res judicata differ fundamentally from the criteria for [812] determining against whom a plea of res judicata may be asserted. The requirements of due process of law forbid the assertion of a plea of res judicata against a party unless he was bound by the earlier litigation in which the matter was decided. (Coca Cola Co. v. Pepsi Cola Co., supra. See cases cited in 24 Am. & Eng. Encyc. (2d ed) 731; 15 Cinn. L. Rev. 349, 351; 82 Pa. L. Rev. 871, 872.) He is bound by that litigation only if he has been a party thereto or in privity with a party thereto. (Ibid) There is no compelling reason, however, for requiring that the party asserting the plea of res judicata must have been a party, or in privity with a party, to the earlier litigation.

No satisfactory rationalization has been advanced for the requirement of mutuality. Just why a party who was not bound by a previous action should be precluded from asserting it as res judicata against a party who was bound by it is difficult to comprehend. (See 7 Bentham's Works (Bowring's ed.) 171.) Many courts have abandoned the requirement of mutuality and confined the requirement of privity to the party against whom the plea of res judicata is asserted. (Coca Cola Co. v. Pepsi Cola Co., supra; Liberty Mutual Insur. Co. v. George Colon & Co., 260 N.Y. 305 [183 N.E. 506]; Atkinson v. White, 60 Me. 396; Eagle etc. Insur. Co. v. Heller, 149 Va. 82 [140 S.E. 314, 57 A.L.R. 490]; Jenkins v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 89 S. C. 408 [71 S.E. 1010]; United States v. Wexler, 8 Fed.2d 880. See Good Health Dairy Food Products Corp. v. Emery, 275 N.Y. 14 [9 N.E. (2d) 758, 112 A.L.R. 401].) The commentators are almost unanimously in accord. (35 Yale L. J. 607; 9 Va. L. Reg. (N. S.) 241; 29 Ill. L. Rev. 93; 18 N.Y. U. L. Q. R. 565, 570; 12 Corn. L. Q. 92.) The courts of most jurisdictions have in effect accomplished the same result by recognizing a broad exception to the requirements of mutuality and privity, namely, that they are not necessary where the liability of the defendant asserting the plea of res judicata is dependent upon or derived from the liability of one who was exonerated in an earlier suit brought by the same plaintiff upon the same facts. (See cases cited in 35 Yale L. J. 607, 610; 9 Va. L. Reg. (N. S.) 241, 245-247; 29 Ill. L. Rev. 93, 94; 18 N.Y. U. L. Q. R. 565, 566-567; 34 C.J. 988-989.) Typical examples of such derivative liability are master and servant, principal and agent, and indemnitor and indemnitee. Thus, if a plaintiff sues a servant for injuries caused by the [813] servant's alleged negligence within the scope of his employment, a judgment against the plaintiff on the grounds that the servant was not negligent can be pleaded by the master as res judicata if he is subsequently sued by the same plaintiff for the same injuries. Conversely, if the plaintiff first sues the master, a judgment against the plaintiff on the grounds that the servant was not negligent can be pleaded by the servant as res judicata if he is subsequently sued by the plaintiff. In each of these situations the party asserting the plea of res judicata was not a party to the previous action nor in privity with such a party under the accepted definition of a privy set forth above. Likewise, the estoppel is not mutual since the party asserting the plea, not having been a party or in privity with a party to the former action, would not have been bound by it had it been decided the other way. The cases justify this exception on the ground that it would be unjust to permit one who has had his day in court to reopen identical issues by merely switching adversaries.

In determining the validity of a plea of res judicata three questions are pertinent: Was the issue decided in the prior adjudication identical with the one presented in the action in question? Was there a final judgment on the merits? Was the party against whom the plea is asserted a party or in privity with a party to the prior adjudication? Estate of Smead, 219 Cal. 572 [28 PaCal.2d 348]; Silva v. Hawkins, 152 Cal. 138 [92 P. 72], and People v. Rodgers, 118 Cal. 393 [46 P. 740, 50 P. 668], to the extent that they are inconsistent with this opinion, are overruled.

In the present case, therefore, the defendant is not precluded by lack of privity or of mutuality of estoppel from asserting the plea of res judicata against the plaintiff. Since the issue as to the ownership of the money is identical with the issue raised in the probate proceeding, and since the order of the probate court settling the executor's account was a final adjudication of this issue on the merits (Prob. Code, sec. 931 [formerly Code Civ. Proc., sec. 1637]; see cases cited in 12 Cal.Jur. 62, 63; 15 Cal.Jur. 117, 120), it remains only to determine whether the plaintiff in the present action was a party or in privity with a party to the earlier proceeding. The plaintiff has brought the present action in the capacity of administratrix of the estate. In this capacity she represents the very same persons and interests that were represented in the earlier hearing on the executor's account. In [814] that proceeding plaintiff and the other legatees who objected to the executor's account represented the estate of the decedent. They were seeking not a personal recovery but, like the plaintiff in the present action, as administratrix, a recovery for the benefit of the legatees and creditors of the estate, all of whom were bound by the order settling the account. (Prob. Code, sec. 931. See cases cited in 12 Cal.Jur. 62, 63.) The plea of res judicata is therefore available against plaintiff as a party to the former proceeding, despite her formal change of capacity. "Where a party though appearing in two suits in different capacities is in fact litigating the same right, the judgment in one estops him in the other." (15 Cal.Jur. 189; Williams v. Southern Pacific Co., 54 Cal.App. 571 [202 P. 356]; Stevens v. Superior Court, 155 Cal. 148 [99 P. 512]; Estate of Bell, 153 Cal. 331 [95 P. 372]. See Chicago, R. & I. R. R. Co. v. Schendel, 270 U.S. 611 [46 S. Ct. 420, 70 L.Ed. 757]; Sunshine A. Coal Co. v. Adkins, 310 U.S. 381, 401 et seq. [60 S. Ct. 907, 84 L.Ed. 1263]; Lee Co. v. Federal Trade Com., 113 Fed.2d 583; and cases cited in 16 N.Y. U. L. Q. R. 158, 159; 38 Yale L. J. 299, 310; 54 Harv. L. Rev. 890.)

The judgment is affirmed.

Gibson, C.J., Shenk, J., Curtis, J., Edmonds, J., Houser, J., and Carter, J., concurred.

[134] *. 30 Am. Jur. Judgments 219-246.

[135] *. 30 Am. Jur. Judgments 219-246.

[136] *. 30 Am. Jur. Judgments 219-246.

16.4.4 Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore 16.4.4 Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore

In Blonder-Tongue Labs., Inc. v. University of Ill. Foundation, 402 U.S. 313 (1971), the US Supreme Court allowed the use of Defensive Non-Mutual Issue Preclusion in federal court in the context of a patent claim. The patentee in that case had earlier brought a patent claim but the court in the first case found the patent invalid. In Blonder-Tongue, the Court held that in future actions asserting the same patent the defendants could assert defensively the earlier holding that the patent was not valid.

That set the stage for the case that follows, which addresses Offensive Non-Mutual Issue Preclusion.

PARKLANE HOSIERY CO., INC., ET AL.

v.

SHORE.

Supreme Court of United States.

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT.

[323] Jack B. Levitt argued the cause for petitioners. With him on the briefs were Irving Parker, Joseph N. Salomon, and Robert N. Cooperman.

Samuel K. Rosen argued the cause and filed a brief for respondent.[1]

Joel D. Joseph filed a brief for the Washington Legal Foundation as amicus curiae.