11 Joinder 11 Joinder

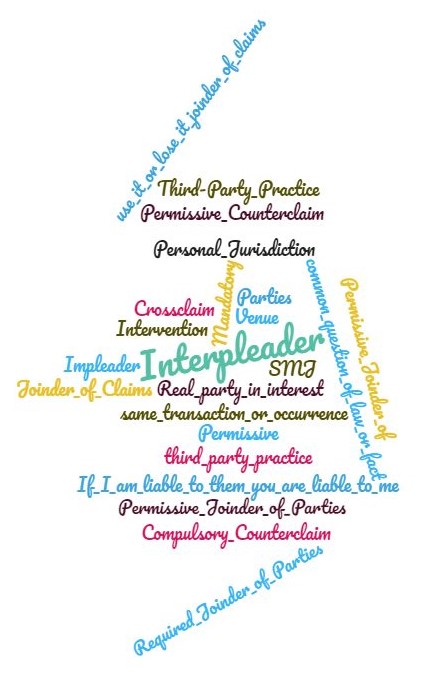

11.1 Joinder Wordcloud 11.1 Joinder Wordcloud

11.2 Joinder in U.S. Federal Court - The Rules 11.2 Joinder in U.S. Federal Court - The Rules

Please read the following carefully.

Rule 13. Counterclaim and Crossclaim

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/rule_13

Rule 14. Third-Party Practice

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/rule_14

Rule 17. Plaintiff and Defendant; Capacity; Public Officers

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/rule_17

(We won't tall much about Rule 17)

Rule 18. Joinder of Claims

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/rule_18

Rule 19. Required Joinder of Parties

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/rule_19

Rule 20. Permissive Joinder of Parties

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/rule_20

Rule 21. Misjoinder and Nonjoinder of Parties

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/rule_21

Rule 22. Interpleader

https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/rule_22

Rule 24. Intervention

11.3 Joinder in U.S. Federal Court - The Tools 11.3 Joinder in U.S. Federal Court - The Tools

Joinder of Claims. Rule 18(a) allows a party bringing a claim to add to it any claim, related or unrelated, that it might have against the other party. There are no subject matter limitations. Subject matter jurisdiction must be established for the claim, though, and venue and personal jurisdiction when brought by a plaintiff.

Joinder of Parties. The joinder of parties rule is broad, but not as open ended as joinder of claims. Rule 20 provides two tests, both of which must be met. Parties may join as plaintiffs if they assert claims “arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences” and there is “any question of law or fact common to all plaintiffs” that will arise in the action. A nearly identical rule applies to joinder of defendants. If you stop to think through these two tests, it is hard to imagine a party whose potential presence arises from the same set of circumstances that would not be joinable. Note that this rule is permissive, not mandatory, and for a variety of reasons (e.g., preserving subject matter jurisdiction, only presenting defendants with deep pockets to the jury) a plaintiff might decide not to include certain defendants. For similar reasons a plaintiff might or might not choose to proceed with co-plaintiffs.

Development of a Lawsuit: The following charts attempt to give a visual depiction of how a lawsuit might develop and become more complicated at the joinder rules are employed.

P1 and P2 bring claims against D1 and D2. P1’s claims against D1 are unrelated to each other, but the first arises from the same transaction or occurrence as the claims against D2. P2’s claims against D1 and D2 will require resolution of “questions of law or fact” related to P1’s first claim against D1.

P1 D1

P2 D2

D1 and D2 bring counterclaims against P1. D1’s claim is related and hence mandatory, D2s is completely unrelated and hence permissive.

P1 D1

P2 D2

D2 brings cross claims against D1. One arises from the same transaction or occurrence; one does not. D1 counterclaims back against D2 with a claim unrelated to either of D2’s claims.

P1 D1

P2 D2

D2 now impleads 3D, claiming that if he owes money to P2, 3D owes money to him.

P1 D1

P2 D2 3D

It can get vastly more complicated, but that is enough to give you a sense.

Remember that for each claim you must establish subject matter jurisdiction, and will be expected to do so in any exam we give in this course. The applicability of venue and personal jurisdiction become murkier in practice, and we won’t test on that.

Claims by Plaintiff. Rule 18(a) allows the plaintiff to bring “as many claims as it has” against any defendant. As we saw, the Rules do not require that additional claims be brought, but as noted we will see when we get to claim preclusion that the plaintiff effectively must assert or lose every claim that arises from the same circumstances. With regard to defendants, as we saw in the brief discussion of joinder of parties, the plaintiff is not quite so unconstrained, but Rule 20 is broad enough to allow the plaintiff to bring as defendants pretty much any defendant where there is a connection between the claims against that defendant and the other defendants in the case. The plaintiff is not required by either the Rules or any other doctrine to join any defendants so long as they are not the sort required under Rule 19, and as we will see the sort required under Rule 19 is a much smaller group than those who might also be liable. The plaintiff may also file claims against other plaintiffs as a cross claim so long as the initial crossclaim meets the relatedness test in Rule 13. Remember also that the plaintiff can turn into a third party defendant upon assertion of a counterclaim or crossclaims from other plaintiffs, and in that circumstance the rules applying to defendants apply to the plaintiff to the extent she is a defendant. Remember that for all claims the requirements of personal jurisdiction, venue, and subject matter jurisdiction must be met aside from the rules.

Claims by Defendant. The range of claims by a defendant is also quite broad. First, she must assert or lose mandatory counterclaims, and may assert permissive counterclaims. For all claims, subject matter jurisdiction must be established. Venue and personal jurisdiction are generally viewed as waived with regard to claims against the plaintiff, and we won’t in this class look at the exceptional or theoretical case. The defendant may also assert crossclaims against other defendants so long as the first crossclaim asserted meets the relatedness test of Rule 13. Again, subject matter jurisdiction must be met. Cross claims are permissive, not mandatory, although counterclaims to a crossclaim can be mandatory, same as other crossclaims. Defendants can also ‘implead’ third parties that it claims are liable to it if it is liable to the plaintiff. Remember that for each claim there must be a basis for federal subject matter jurisdiction.

Pro Mnemonic Tip. If the joinder device involved begins with a C (such counterclaim or crossclaim) it is between parties already in the case. If it begins with the letter I (such as impleader or intervention) it involves bringing a new party into the case.

Now we will consider the various rules one at a time.

Rule 13. Counterclaim and Crossclaim. Counterclaims come in two varieties – compulsory and permissive. In general, if a claim arises out of the transaction or occurrence that underlies the plaintiff’s claim, it is a compulsory counterclaim. The exceptions are if it is the subject of an action that predated the plaintiff’s claim, if it requires adding a party over whom the court cannot get jurisdiction, or if the original claim was in rem or quasi in rem and the counterclaim would not be. The consequences of a counterclaim being compulsory are simple – if not brought, it cannot be brought in a different action. Permissive counterclaims are all counterclaims that are not mandatory.

Let’s see how this works. Perry Plaintiff sues Don Defendo claiming a breach of contract relating to Plaintiff’s of a million widgets to Defendo. Plaintiff claims that Defendo has only paid part of the purchase price. Defendo has two potential counterclaims. One would assert that the widgets were defective and that not only should Defendo not pay, but that he is entitled to get back the money he did pay plus special damages incurred because he was unable to deliver the widgets to his customers. The other arises from a sale of woodgets two years before, and which has no factual overlap with widget transaction. Whether or not Defendo likes the forum Plaintiff has selected, he must bring the widget counterclaim as a compulsory counterclaim. The other claim he may bring as a permissive counterclaim (and may choose to in order to consolidate his claims against Plaintiff or to increase his settlement leverage) or he can bring it in a separate court at a different time. What happens if Defendo fails to bring the widget claim as a compulsory counterclaim but files it in a different court? It will be dismissed because it should have been brought as a compulsory counterclaim.

Crossclaims are claims between two parties on the same side of the case – for example, between two plaintiffs or between two defendants. The first crossclaim requires a connection to the plaintiff’s claims. It is allowed only “if the claim arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the original action or of a counterclaim, or if the claim relates to any property that is the subject matter of the original action.” Once that claim is filed, however, Rule 18 kicks in and additional unrelated claims can be joined, and the party sued must respond with compulsory counterclaims and may respond with permissive counterclaims.

Rule 14. Third-Party Practice. Students often get confused about impleader. It is important to understand that impleader addresses a particular kind of situation, and does not provide a vehicle for bringing in all kinds of third parties, even if an argument can be made that they are the truly liable party. Look at the rule. It allows a defendant to bring in a defendant who “is or may be liable to it for all or part of the claim against it.” That does not mean “may be liable instead.” We saw an example of impleader in the Asahi case. The plaintiff sued the manufacturer of the motorcycle tire. The manufacturer of the motorcycle tire concluded – without necessarily admitting – that if there was a problem with the motorcycle tire, it was because the valve on the tire failed. The valve manufacturer was then impleaded on the theory that it should pay to the tire manufacturer all or part of the damages the tire manufacturer had to pay to the plaintiff. This was the part of the litigation that was still alive when the Supreme Court addressed the personal jurisdiction issues. Other common applications include guarantors and indemnitors (if I am held liable you promised to make me whole) and insurers. Note that the defendant/third party plaintiff does not have to admit liability to the original plaintiff but can bring in the third party defendant in case liability is established. Note also the key point – it must involve liability by the third party defendant to the original defendant/third party plaintiff related to the original claim.,

So, imagine a case where Perry Plaintiff is suing Don Defendo for an automobile accident in which he claims Defendo veered onto the sidewalk and ran him down. Defendo now wishes to implead Arnie Insurer who has insured Defendo against claims relating to his automobile driving, but has refused to defend this lawsuit. That would be a proper impleader. On the other hand, assume that Defendo wishes to implead Danny Driver, based on a claim that it was Driver, not Defendo, who actually struck Plaintiff. That would not be a proper impleader. Do you see why?

Rule 17. Plaintiff and Defendant; Capacity; Public Officers. Under the common law, actions had to be brought in the name of the party holding the ultimate legal right. Assignees, for example, could not sue in their own names. This led to contortions in pleading, and was abandoned under the pleading codes and also in equity. This rule carries forward the choice by the codes and equity to look not at nominal holders of rights but at the party – such as an assignee – actually affected. The party actually holding the right should be the party in the caption asserting or defending the claim. We won’t spend any more time on this rule.

Rule 18. Joinder of Claims. Rule 18(a) is very straightforward – so far as pleading goes, a plaintiff can bring any claim it has against a defendant. The same applies to those asserting counterclaims or crossclaims (so long as the first crossclaim against a party meets the relatedness test of Rule 13).

Rule 19. Required Joinder of Parties. Rule 19 can be difficult. A rule 19 situation arises when there is a potential party not joined in the lawsuit (Absentee) and someone argues that Absentee really, really needs to be part of the lawsuit. In a typical Rule 19 situation neither the plaintiff (who could have joined anyone who meets the standards of Rule 20, assuming SMJ, PJ, and Venue are met) or Absentee (who could have intervened, assuming SMJ) really want Absentee to be in the lawsuit. Rule 19 first sets out a three-part test. The test is of the either-or type, where meeting the standards of any one of the three parts of the test makes the Absentee a party to be joined if feasible. These tests are whether the party can give full relief without Absentee being joined, whether some interest of Absentee may be impaired if Absentee is not joined, or if failure to join Absentee can lead to multiple or inconsistent obligations (as in, an order from a different court ordering the defendant to do give to Party X an object that the first court might order the Defendant to give to Party Y).

Imagine that Student Z brings a lawsuit to order Evil Professor to deliver to her the Magic Water Bottle of Shenzhen, which Evil Professor took from the desk of Student Absentee and which Absentee is known to claim ownership of. Would Absentee’s interest be impaired if the court orders the bottle delivered to Student Z? Possibly. Might Evil Professor face inconsistent obligations if in a different suit Absentee obtains an order directing the that water bottle be delivered to her? Absolutely.

The first part is the easy part. Now let’s assume that the party to be joined cannot be joined – there is no personal jurisdiction or venue or inclusion of Absentee would destroy subject matter jurisdiction. The question then is whether to dismiss the lawsuit or to proceed without Absentee. The rule sets out a four part test to help the court work through that issue. We will read a case applying that rule so hold tight.

One thing to remember about Rule 19 from the perspective of transnational litigation is that the rule comes into play when a party cannot be joined - either because there is no personal jurisdiction or because adding the party would destroy subject matter jurisdiction. One does not to be as smart as you are to immediately see how those situations could arise in litigation involving overseas defendants.

Rule 20. Permissive Joinder of Parties. As the name of the rule suggests, Rule 20 allows but does not require joinder of parties. The test is two part – same transaction or occurrence plus a common question of law or fact. As noted above, for a number of reasons parties might choose not to join all permissible parties. For example, a defendant who would destroy federal subject matter jurisdiction can be left out. Similarly, a defendant who has no money may not be joined because the plaintiff does not want a verdict returned against a judgment proof defendant. Similar logic applies to co-plaintiffs. A plaintiff might want a very sympathetic co-plaintiff to be part of the same lawsuit; on the other hand, plaintiff might not want to be joined in a lawsuit with a co-plaintiff the presence of whom will in some way undercut the narrative plaintiff wants to present.

While plaintiff gets to choose whom to join, the plaintiff’s choice is not always the final word. First, in some cases, parties can be brought in under Rule 19. In addition, under Rule 24 parties can choose to join the lawsuit as defendants or plaintiffs through intervention.

Rule 21. Misjoinder and Nonjoinder of Parties. Rule 21 is another example of the Federal Rules trying to allow flexibility, and avoiding having results dictated by formalities rather than the ultimate merits. Under the common law, mistakes in joinder could lead to dismissal of a suit. Rule 21 gives the court power to deal flexibly so as to get the right array of parties before the court. As with Rule 17, we will not spend any more time on this.

Rule 22. Interpleader. Imagine you are walking down the street and there it is in front of you - The Magic Water Bottle of Shenzhen. In order to make sure it is not accidentally destroyed or discarded, you pick it up and carry it home. That said, you know it is not yours and you are happy to deliver it to its rightful owner. Imagine, though, that the issue of the rightful owner is not self-evident. Professor Evil steps forward and claims he owns it because he took it from Student A as punishment for the student not paying attention in class. Student A in turn asserts that Professor Evil had no right to take it and she is the true owner because Student B had given it to her when they were dating. Now imagine that Student B shows up and says that he had loaned, not given, the Magic Water Bottle of Shenzhen to Student A and demands that it be returned to him. What are you to do? Alternatively, imagine InsurCo has contractually agreed to provide $1,000,000 in insurance to BigCo. Now imagine that a typhoon hits the factory of BigCo, causing a release of BigCo’s latest production run of AI powered robot watchdogs, who run loose in the town biting people, leading to well more than $1,000,000 in damages.BigCo also has 1,000,000 in damages to its plant. InsurCo agrees that it owes the $1,000,000 under the policy, but doesn’t know who should get it.

In both cases, interpleader is the answer. The asset is placed in the custody of the court, and an interpleader action is used to determine who gets it.

Interpleader can get complicated because it comes in both statutory and a Federal Rules version. For our purposes, it’s enough that you know that this kind of procedural option exists; we will not spend time examing the fine points of how it works.

Rule 24. Intervention. Think back to our discussion under Rule 19. What if, instead of being forced to join the lawsuit, Absentee hears about it and wants to join? Rule 24 provides the means. Intervention as of right resembles Rule 19 in some respects. Setting aside intervention based on a statute, a party may intervene as of right when “claims an interest relating to the property or transaction that is the subject of the action, and is so situated that disposing of the action may as a practical matter impair or impede the movant's ability to protect its interest, unless existing parties adequately represent that interest.” If that fails, a party may intervene with the permission of the court. Note how permissive Rule 24 is. If the court approves, it only takes one “common question of law or fact” for intervention to be proper.

The core idea behind liberal joinder is efficiency. Systems of procedure can embody different choices about what can and should be contained in a single lawsuit. The approach taken by the common law writs, for example, was to severely limit what can be included to a single claim. The federal rules take a very different approach. They support bringing in one lawsuit all claims related to a set of facts.

In allowing broad joinder of claims and parties the federal rules pursue a goal of efficiency. Rather than splitting litigation over one incident into piecemeal litigation, the federal rules support and to some extent require bringing all the claims together for resolution at the same time.

This approach has advantages and costs. The goal of efficiency is indeed served by allowing witness testimony and exhibits to bear on multiple claims against multiple parties. On the other hand, the complexity of litigation that is allowed by the federal rules has costs of its own. Juries may struggle to keep track of how evidence bears on multiple counts, and keeping straight the varying legal standards that might be applied to a single set of facts can also be a challenge. Complexity also can arise in pretrial proceedings, as both discovery and motion practice are complicated by sorting through the many different kinds of claims that can be brought.

Nonetheless, the federal rules have firmly embraced liberal joinder of claims and parties. While you should bring your systems engineer mindset to bear on whether you agree this is a good idea, we also need to work through how the system established under the federal rules operates.

Mandatory and Compulsory – Litigant Choice. One aspect of the federal rules is the degree to which bringing claims into the same lawsuit is forced by mandatory joinder rules or merely allow by permissive joinder rules. This encompasses not just the rules themselves, but also doctrines that operate aside from the rules.

One of those doctrines is claim preclusion, also known as res judicata. Claim preclusion operates to prevent relitigation of the same claim over and over again. Put simply if you bring a lawsuit and lose – or win – you cannot bring exactly that claim again in hopes of the different and better result. Back in the days of the common law writs, claim preclusion barred relitigation of the same writ. At the same time, pleading under the writs allowed coming back to court with a different writ if the claim was barred because the wrong writ had been asserted.

Today, that is not the rule. Today, any claim arising from the same transaction or occurrence that could have been brought at the time the original lawsuit was brought will be barred under the doctrine of claim preclusion. For our purposes here, this means that as a practical matter litigants are not only permitted but effectively required to bring any causes of action relating to a transaction or occurrence or lose them forever. We will return to the issue of claim preclusion later in the course, but for now you can think of claim preclusion as akin to a rule that requires claimants to bring all claims arising from the same transaction or occurrence that can be brought in that forum or lose them. Think of it as a "use it or lose it" requirement with regard to all claims against the defendant arising from the transaction or occurrence that can be brought in that court, regardless of the legal theory.

A similar rule operates both under the doctrine of claim preclusion and under the rules with regard to counterclaims. Rule 13 covers counterclaims, and divides them into mandatory and permissive counterclaims. Mandatory counterclaims are those that arise from the same transaction or occurrence as the plaintiff’s claim. Rule 13 a requires that these counterclaims be brought in the federal action or lost forever. Put differently, a defendant cannot choose to file a separate action asserting what might be mandatory counterclaims, nor can the defendant save the counterclaim for use later. A use it here and now or lose it rule applies.

Other claims that might be brought are permissive. For example, neither plaintiffs nor defendants are required to bring in the same action any unrelated claims they may have, but they may bring those claims (assuming subject matter jurisdiction, personal jurisdiction, and venue). A defendant may bring as a permissive counterclaim any claim she has against the plaintiff, regardless of whether or not it is related in any way to the plaintiff’s claim against the defendant. (Note, as we will discuss below, that the other elements of selecting a proper courts must still be established).

Cross-claims are also permissive. A cross-claim is a claim that one defendant has against another defendant or that one plaintiff has against another plaintiff. As we will see, the first such cross-claim needs to arise from the same transaction or occurrence as an original claim by the plaintiff. Even though such a cross claim is related to the overall litigation, the cross claimant can choose to file it in another location or at a later time.

Also not mandatory are claims where a party seeks to implead another. In some cases, the defendant might be able to claim that if it is liable, another party is liable to it. We saw such a claim in the Asahi case where the tire manufacturer impleaded the manufacturer of the valve on the tire. While impleading is permitted, it is not required, and can be pursued as a separate action.

Permissive joinder also applies to joinder of parties. In general, a claimant is not required to join in the action every potentially liable defendant. There are some cases where party is considered under rule 19 to be both necessary and indispensable, but in the average run-of-the-mill case where there are multiple, potentially liable defendants, the plaintiff can choose which one or ones it chooses to pursue.

Again, bring your systems engineer eye to the issue of mandatory and permissive joinder of claims and parties. From a system standpoint, when does it make sense to require claims and parties to be joined in a single action whether or not the parties prefer it, and when does it make sense to allow them to make their own decisions?

Overlap with PJ, SMJ, Venue. An important thing to remember about joinder of claims and parties is that the federal rules only apply is that the federal rules do not displace or set aside the other doctrines that govern where and how a case may be brought. These requirements still apply. For each claim, personal jurisdiction, venue, and subject matter jurisdiction must be established.

For counterclaims, plaintiffs have been held unable to object to venue or personal jurisdiction. This may be seen as a kind of waiver, as plaintiff did choose the initial forum. Subject matter jurisdiction is an absolute requirement for all claims.

Joinder of Claims Reviewed.

Be able to fill in the following chart.

|

Joinder of Claims Device & FRCP No. |

Definition? |

Who Uses? (P , D or both?) |

Elements? |

Mandatory? |

|

1. 18a (the “kitchen sink” rule) |

||||

|

2. 13(g) Crossclaims |

||||

|

3a. 13(a) compulsory counterclaims |

||||

|

3b. 13(b) permissive counterclaims |

||||

|

4. 20(a) Joinder |

||||

|

5. 13(h) Joinder |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. 14a & b 3rd party claim/ impleader |

11.4 M.K. v. Tenet 11.4 M.K. v. Tenet

M.K. et al., Plaintiffs, v. George TENET, Director, Central Intelligence Agency, et al., Defendants.

No. CIV.A. 99-0095(RMU).

United States District Court, District of Columbia.

July 30, 2002.

*135 MEMORANDUM OPINION

Granting the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Amend the Complaint; Denying the Defendants’ Motion to Sever

I. INTRODUCTION

Employees of the United States Central Intelligence Agency (“CIA”) brought this as-yet-uncertified class action against that agency, that agency’s director, George Tenet, and 30 unnamed “John and Jane Does” (collectively “the defendants”). In a four-count amended complaint, six plaintiffs allege that the CIA violated the Privacy Act of 1974, as amended, 5 U.S.C. § 552a (“Privacy Act”), and several of their constitutional rights. In a proposed second amended complaint, which is a subject of this memorandum opinion, 15 plaintiffs altogether1 allege that the CIA obstructs the plaintiffs’ efforts to obtain assistance of counsel, thereby causing an invasion of privacy among other alleged violations of the Constitution. Additionally, the proposed second amended complaint states that beginning in 1997, the defendants’ policy and practice associated with the alleged obstruction of counsel violates the Privacy Act. Furthermore, the plaintiffs claim that the defendants’ alleged practice of obstruction of counsel violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000 et seq (“Title VII”). Before the court is the plaintiffs’ motion to amend the complaint with their proposed second amended complaint pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 15, and the defendants’ motion to sever the claims of the six existing plaintiffs pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 21. After consideration of the parties’ submissions and the relevant law, the court grants the plaintiffs’ motion to amend the complaint and denies the defendants’ motion to sever.

II. BACKGROUND

A. Factual Background

On January 13, 1999, plaintiffs M.K. and Evelyn M. Conway filed the complaint initiating the present action. On April 12, 1999, the plaintiffs filed an amended complaint adding M.D.E., R.B., Grace Tilden, Vivian Green, and George D. Mitford as plaintiffs.2 By order dated August 4, 1999, the court approved the voluntary dismissal without prejudice of plaintiff Green’s claims. Order dated August 4, 1999. By order dated March 3, 2000, the court approved the voluntary dismissal without prejudice of plaintiff M.D.E.’s claims. Order dated March 3, 2000. On November 30, 2001, the plaintiffs filed a proposed second amended complaint adding *136J.T., J.B., C.B., P.C., P.C.I., C. Lynn, Nathan (P), Elaine Livingston (P), and Betty E. Ya-les (P) as nine new plaintiffs.3 Second Am. Compl. (“2d Am. Compl”) at 2 n. 2. The court identifies the six existing plaintiffs as M.K., Conway, Tilden, R.B., C.T., and Mitford. Beginning in 1997 and continuing to the present, the plaintiffs claim that the defendants’ acts and omissions in denying the plaintiffs access to effective assistance of counsel violate the plaintiffs’ rights under the First, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments of the United States Constitution, the Privacy Act, and Title VII.2d Am. Compl. 1111 2-5, 444. Specifically, the nine new plaintiffs, in addition to the six existing plaintiffs, allege in the second amended complaint that the defendants’ September 4, 1998 notice entitled “Access to Agency Facilities, Information, and Personnel by Private Attorneys and Other Personal Representatives” deprives the plaintiffs’ counsel access to “official information” pertaining to the plaintiffs’ employment matters. Id. 1123. The defendants’ invocation of the September 4, 1998 notice has allegedly resulted in a denial of the plaintiffs’ access to CIA documents, policies, procedures, and regulations, thereby preventing counsel from effectively advising the plaintiffs of their rights. Id. The plaintiffs claim that the defendants have “willfully and intentionally failed to maintain accurate, timely, and complete records pertaining to the plaintiffs in their personnel, security, and medical files so as to ensure fairness to [the] plaintiffs, thus failing to comply with 5 U.S.C. § 552a(e)(5) [of the Privacy Act].” Am. Compl. 11116. What follows are the six existing plaintiffs’ factual allegations relating to the inaccuracy of the records in question.

Plaintiff M.K. complains of a letter of reprimand placed in her personnel file in April 1997, which concerns her responsibility for the loss of top-secret information contained on laptop computers sold at an auction. Id. 111115, 116a. Plaintiff Conway complains of a finding by the CIA Human Resources Staff or Personnel Evaluation Board concerning her ineligibility for foreign assignment. Id. HH23, 116b. Plaintiff Conway additionally avers that the CIA notified her of this finding in March 1997. Id. 1123.

Plaintiff C.T. complains of a Board of Inquiry determination that she was not qualified for the position she held with the CIA. Id. H1167, 116e. This Board of Inquiry convened after “early 1998.” Id. 111166-67. Plaintiff Mitford complains of receiving two negative Performance Appraisal Reports and two negative “spot reports” on unspecified dates in 1997, allegedly based on false information. Id. 111181, 116g. Plaintiff R.B. complains of inaccurate counter-intelligence and polygraph information contained in his file. Id. H 116f. Plaintiff R.B.’s last polygraph exam took place in February 1996. Id. H 76. Plaintiff Tilden makes no allegations relating to Count IV of the amended complaint (‘Violation of the Privacy Act”).

B. Procedural History

On March 24, 1999, the defendants filed a motion to dismiss pursuant to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 12(b)(1), (2), (3), and (6). On March 23, 2000, this court issued a Memorandum Opinion and supplemental order granting in part and denying in part the defendants’ motion to dismiss. M.K v. Tenet, 99 F.Supp.2d 12 (D.D.C.2000); Order dated Mar. 23, 2000. On April 20, 2001, the defendants filed a “motion for reconsideration” of that ruling pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 54(b), seeking to dismiss the plaintiffs’ remaining due process and Privacy Act claims. On November 30, 2001, the plaintiffs filed a motion for leave to file the second amended complaint along with the proposed second amended complaint. On December 3, 2001, this court issued a Memorandum Opinion and supplemental order granting in part and denying in part the defendants’ motion for reconsideration under Rule 54(b). M.K v. Tenet, 196 F.Supp.2d 8 (D.D.C.2001); Order dated Dec. 3, 2001. On December 4, 2001, this court set out the parties’ filing deadlines in its “Initial Scheduling and Procedures Order.” Order dated Dec. 4, 2001. On January 2, 2002, the defendants filed their instant motion to sever the claims of the six existing plaintiffs pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 21. On *137March 6, 2002, the plaintiffs filed a certificate of notification informing the CIA and the court of the 30 Doe defendants’ identities. For the reasons that follow, the court grants the plaintiffs’ motion to amend the complaint and denies the defendants’ motion to sever.

III. ANALYSIS

A. Legal Standard for a Motion to Amend

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 15(a) provides that a “party may amend the party’s pleading once as a matter of course at any time before a responsive pleading is served____” Fed. R. Civ. P. 15(a). Once a responsive pleading is filed, “a party may amend the party’s pleading only by leave of the court or by written consent of the adverse party; and leave shall be freely given when justice so requires.” Id.; see also Foman v. Davis, 371 U.S. 178, 182, 83 S.Ct. 227, 9 L.Ed.2d 222 (1962). The D.C. Circuit has held that for a trial court to deny leave to amend is an abuse of discretion unless the court provides a sufficiently compelling reason, such as “undue delay, bad faith, or dilatory motivef,] ... repeated failure to cure deficiencies by [previous] amendments [or] futility of amendment.” Firestone v. Firestone, 76 F.3d 1205, 1208 (D.C.Cir.1996) (quoting Foman, 371 U.S. at 182, 83 S.Ct. 227). The court may also deny leave to amend the complaint if it would cause undue prejudice to the opposing party. Foman, 371 U.S. at 182, 83 S.Ct. 227. In sum, a district court has wide discretion in granting leave to amend the complaint.

A court may deny a motion to amend the complaint as futile when the proposed complaint would not survive a Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss. James Madison Ltd. v. Ludwig, 82 F.3d 1085, 1099 (D.C.Cir.1996) (internal citations omitted). When a court denies a motion to amend a complaint, the court must base its ruling on a valid ground and provide an explanation. Id. “An amendment is futile if it merely restates the same facts as the original complaint in different terms, reasserts a claim on which the court previously ruled, fails to state a legal theory, or could not withstand a motion to dismiss.” 3 Moore’s Federal Practice § 15.15[3] (3d ed.2000).

B. Legal Standard for Severance

Claims against different parties can be severed for trial or other proceedings under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 20(b), 21, and 42(b). In re Vitamins Antitrust Litig., 2000 WL 1475705, at 16-17, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7397, at * 74 (D.D.C.2000) (Hogan, J.). Specifically, Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 21 governs the misjoinder of claims. Brereton v. Communications Satellite Corp., 116 F.R.D. 162 (D.D.C.1987) (Richey, J.) (holding that an appropriate remedy for mis-joinder is severance of claims brought by the improperly joined party). Rule 21 provides, in relevant part:

Misjoinder of parties is not ground for dismissal of an action. Parties may be dropped or added by order of the court on motion of any party or of its own initiative at any stage of the action and on such terms as are just. Any claim against a party may be severed and proceeded with separately.

Fed. R. Crv. P. 21. In determining whether the parties are misjoined, the joinder standard of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 20(a) applies. Rule 20(a) provides, in relevant part:

All persons may join in one action as plaintiffs if they assert any right to relief jointly, severally, or in the alternative in ■ respect of or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence or series of transactions or occurrences and if any question of law or fact common to all these persons will arise in the action.

The purpose of Rule 20 is to promote trial convenience and expedite the final resolution of disputes, thereby preventing multiple lawsuits, extra expense to the parties, and loss of time to the court as well as the litigants appearing before it. Anderson v. Francis I. duPont & Co., 291 F.Supp. 705, 711 (D.Minn.1968). The determination of a motion to sever is within the discretion of the trial court. In re Nat’l Student Marketing Litig., 1981 WL 1617, at *10 (D.D.C.1981) *138(Parker, J.); Bolling v. Mississippi Paper Co., 86 F.R.D. 6, 7 (N.D.Miss.1979).

There are two prerequisites for joinder under Rule 20(a): (1) a right to relief must be asserted by, or against, each plaintiff or defendant relating to or arising out of the same transaction or occurrence or series of transactions or occurrences, and (2) a question of law or fact common to all of the parties must arise in the action. Mosley v. Gen. Motors Corp., 497 F.2d 1330, 1333 (8th Cir.1974). “In ascertaining whether a particular factual situation constitutes a single transaction or occurrence for purposes of Rule 20, a case by case approach is generally pursued.” Id.

Additionally, “the court should consider whether an order under Rule 21 would prejudice any party, or would result in undue delay.” Id.; see also Brereton, 116 F.R.D. at 163 (stating that Rule 21 must be read in conjunction with Rule 42(b), which allows the court to sever claims in order to avoid prejudice to any party). The court may also consider whether severance will result in less jury confusion. Henderson v. AT & T Corp., 918 F.Supp. 1059, 1063 (S.D.Tex.1996) (directing in part that the claims of former employees from separate offices, which alleged various combinations of race, age, and national origin discrimination be severed because the claims were “highly individualized” and would be “extraordinarily confusing for the jury”); but see In re Vitamins Antitrust Litig., 2000 WL 1475705, at 17, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7397, at *75-76 (stating that courts “consistently deny motions to sever where [the] plaintiffs allege that [the] defendants have engaged in a common scheme or pattern of behavior” (citing Brereton, 116 F.R.D. at 164)).

C. The Court Grants the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Amend the Complaint

The plaintiffs ask this court for leave to file their second amended complaint in order “to address deficiencies found by the [c]ourt and to avail themselves of favorable intervening precedent,” referring to the D.C. Circuit’s decision in Jacobs v. Schiffer, 204 F.3d 259 (D.C.Cir.2000).4 Pis.’ Mot. at 2, 5. The plaintiffs state that the D.C. Circuit’s decision in Jacobs supports the plaintiffs’ claim that the defendants have violated the plaintiffs’ First Amendment rights by not allowing the plaintiffs to disclose to their attorneys government documents that are available to the plaintiffs.5 Jacobs, 204 F.3d *139at 261; Pis.’ Mot. at 5. Additionally, the plaintiffs seek to “address subsequent arguments raised by [the][d]efendants in their [m]otion for [reconsideration filed on April 20, 2001, and to add additional claims and [plaintiffs, all related through [the][d]efen-dants’ pattern and practice of obstruction of counsel.” Pis.’ Mot. at 2. Also, the plaintiffs seek to expand their allegations of the defendants’ violations of their right to effective assistance of counsel under the First Amendment to a “wide range of wrongful conduct,” as compared to the “plaintiffs’ initial allegations that the defendants merely refused to provide access to government documents.” Id. at 5.

The defendants challenge the plaintiffs’ proposed amendment asserting that the plaintiffs’ “factually diverse” claims are unrelated to each other. Defs.’ Opp’n at 1-2. Specifically, the defendants argue that “neither the existing six plaintiffs nor the proposed nine plaintiffs have alleged claims factually in common with one another.” Id. According to the defendants, the “wide range of wrongful conduct” that the plaintiffs allege in their proposed second amended complaint arises out of “unique sets of facts and circumstances, involving completely different types of [a]gency actions, proceedings or personnel matters, such as employment terminations, revocations of security clearances, forced resignations, disciplinary proceedings, failure to obtain promotions ... and retaliation.” Id. The plaintiffs’ proposed second amended complaint, however, cites to numerous obstruction-of-counsel situations, including denying counsel access to requested CIA policies, procedures, and documents upon request. 2d Am. Compl. 111124-27, 36-37, 64. Additionally, the plaintiffs allege that when they requested the presence of counsel, the defendants failed to accommodate that request and attempted to restrict the plaintiffs’ access to counsel. Id. HH59, 62, 65.

The defendants counter that they would suffer “undue prejudice” if the court grants the plaintiffs’ motion to amend. Defs.’ Opp’n at 6 (citing Atchinson v. District of Columbia, 73 F.3d 418, 425 (D.C.Cir.1996) (quoting Foman, 371 U.S. at 182, 83 S.Ct. 227)). The defendants further assert that the burden on the defendants “against fifteen substantially different sets of facts and legal arguments in one case far outweighs any practical benefit that might accrue from considering” the eases of the six existing plaintiffs and the nine new plaintiffs. Id.

1. The Plaintiffs Have Not Repeatedly Failed to Cure Deficiencies by Previous Amendments

The plaintiffs seek leave to amend their complaint to address prior deficiencies6 named by the court in its March 2000 Memorandum Opinion and to avail themselves of intervening legal precedent. Pis.’ Mot. at 5. As such, the court deems these justifications reasonable and concludes that the deficiencies that the plaintiffs seek to address are not “repeated failure[s] to cure deficiencies by amendments previously allowed.” Foman, 371 U.S. at 182, 83 S.Ct. 227.

In determining whether undue prejudice will result, however, the D.C. Circuit has suggested that the court consider whether amendment of a complaint would require additional discovery. Atchinson, 73 F.3d at 426 (citing Alley v. Resolution Trust Corp., 984 F.2d 1201, 1208 (D.C.Cir.1993) (remanding the case for the district court to allow amendment where the plaintiffs assured the court of appeals that additional discovery would be unnecessary)). If additional discovery will result, then this factor may weigh negatively on the plaintiffs’ instant motion to *140amend the complaint. Id. The plaintiffs point out that the ease at bar has yet to enter the discovery stage. Pis.’ Reply at 1-2. The defendants, however, fear the potential burdens associated with excessive discovery and argue that the “myriad claims presented by each plaintiff and the number of defendants” in the second amended complaint would make it “incredibly burdensome to prepare an answer, conduct discovery, or file a dis-positive motion.” Defs.’ Opp’n at 26. Furthermore, the defendants argue that “discovery in a case that essentially challenges and finds fault with nearly every [ajgency proceeding and practice would be unmanageable, particularly where the business of the defendant is national security and intelligence gathering.” Id. at 28. But the defendants misconstrue the additional discovery factor as one that discourages discovery altogether. In a ease such as this in which discovery has yet to occur, it would defy logic to deny the plaintiffs an opportunity to amend the complaint on the basis that additional discovery will result. While it is conceivable that a great deal of discovery may result from the addition of new claims, 30 defendants, and nine plaintiffs in the proposed second amended complaint, this does not constitute evidence of undue prejudice to deny the plaintiffs’ instant motion. Teachers Retirement Bd. v. Fluor Corp., 654 F.2d 843, 856 (2d Cir.1981) (stating that the plaintiffs did not unduly prejudice the defendants because the plaintiffs requested leave to amend when no trial date was set by the court and the defendants had not filed a motion for summary judgment).

2. The Plaintiffs’ Proposed Second Amended Complaint Satisfies Rule 8’s Requirements

The defendants challenge the plaintiffs’ proposed second amended complaint under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure Rule 8, stating that the plaintiffs’ pleading “is not a pleading [that] [the] defendants can reasonably answer or that can reasonably be expected to control discovery.” Defs.’ Opp’n at 26. In Atchinson, the D.C. Circuit stated that Rule 8(a)(2) requires that a complaint include “a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief.” 73 F.3d at 421. Additionally, Rule 8(e) states that “each averment of a pleading shall be simple, concise, and direct” and further instructs courts to construe “all pleadings ... to do substantive justice.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(e); Atchinson, 73 F.3d at 421. Accordingly, “under the Federal Rules, the purpose of pleading is simply to ‘give the defendant fair notice of what the plaintiffs claim is and the grounds upon which it rests,’ not to state in detail the facts underlying the complaint.” Id. (citing Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 47, 78 S.Ct. 99, 2 L.Ed.2d 80 (1957); Sinclair v. Kleindienst, 711 F.2d 291, 293 (D.C.Cir.1983)).

In this case, the plaintiffs’ first amended complaint was 44 pages in length compared to the plaintiffs’ proposed 219-page second amended complaint. Compare Am. Compl. to 2d Am. Compl. Although the defendants insist that the court should strike the plaintiffs’ proposed second amended complaint, the defendants fail to point out any specific Rule 8 violations. Defs.’ Opp’n at 27. Stating only that the second amended complaint is a “detailed and lengthy pleading,” the defendants also cite to several cases where courts have denied amendment on a variety of distinguishable grounds. Id. at 26-27 (citations omitted).7

The court concludes that the length of the plaintiffs’ proposed second amended complaint is reasonable, considering that the plaintiffs have added new claims, new plaintiffs, and new defendants. In the plaintiffs’ second amended complaint, each of the 15 plaintiffs’ individual averments are approximately 12 pages in length, while the remainder of the second amended complaint requests several forms of relief and alleges common questions of law and fact. 2d Am.

*141Compl. til 14-555. While the plaintiffs certainly could “state [in less] detail the facts underlying” their claims, the court notes that most of the individual paragraphs of then-proposed second amended complaint are “simple, concise, and direct.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(e); Atchinson, 73 F.3d at 421. For example, in stating facts to construe her privacy act claim, plaintiff Tilden states in the second amended complaint that:

[o]n or about August 8, 2000, [p]laintiff Tilden reviewed her CIA Office of Medical Services (“OMS”) file and first learned that it omit[t]ed a favorable psychological evaluation performed on her in 1993, which determined [that] she was fit for overseas assignment. Upon inquiry, OMS advised her to examine her medical file to locate the psychological evaluation.

2d Am. Compl. H157. Moreover, the court follows Rule 8(e)’s mandate that courts must construe “all pleadings ... to do substantive justice.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(e); Atchinson, 73 F.3d at 421. In doing so, the court determines that there is no basis for the defendants’ Rule 8 challenge.

Indeed, to bar the plaintiffs from amending their complaint would contravene Rule 15(a)’s underlying policy of granting leave to amend freely as justice requires. Foman, 371 U.S. at 182, 83 S.Ct. 227. This is not to say that in every instance, the court must allow the requested amendment, but to conclude otherwise in this case would positively bar the plaintiffs from asserting claims that may prove meritorious. Besides, as stated earlier, the case has yet to enter the discovery phase, which distinguishes this case from other cases where amendment is sought after discovery has started or closed. Atchinson, 73 F.3d at 426 (citing Williamsburg Wax Museum v. Historic Figures, Inc., 810 F.2d 243, 247-48 (D.C.Cir.1987) (affirming a district court’s denial of leave to amend more than seven years after the filing of the initial complaint because new discovery was necessary)); Alley, 984 F.2d at 1208.

D. The Court Denies the Defendants’ Motion to Sever the Claims of the Six Existing Plaintiffs

The court now addresses the defendants’ instant motion to sever. In the defendants’ view, the plaintiffs’ obstruction-of-counsel claim consists of “a series of unrelated, isolated grievances, unique to each plaintiff, each of which would have to be decided on its own set of law and facts, and each potentially presenting a ‘novel’ constitutional claim.” Defs.’ Reply at 1 (quoting M.K., 99 F.Supp.2d at 30). Thus, the defendants ask this court to sever the claims of the six existing plaintiffs8 under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 21. Defs.’ Mot. at 5, 8. By the same token, the defendants ask the court to deny the plaintiffs’ proposed Rule 20 join-der of the nine new plaintiffs and the 30 new “Doe” defendants. Defs.’ Mot. at 3.

The plaintiffs, however, argue that the court should not sever the six existing plaintiffs because both prongs of Rule 20(a)’s join-der requirement are satisfied. The court need not extensively address the joinder of the six existing plaintiffs’ new claims because the court is convinced that under the unrestricted joinder provision of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 18, such joinder of new claims is possible. 3 Moore’s Federal Practice § 21.02[1] (3d ed.2000). To wit, it suffices to state that “Rule 18 permits the claimant to join all claims the claimant may have against the defendant regardless of transactional relatedness.” Id. As such, the court focuses its analysis on the Rule 20 joinder issue raised by the defendants.

The plaintiffs cite to the first prong of Rule 20(a), also known as the “transactional test,” and argue that the defendants’ acts and omissions pertaining to the plaintiffs’ obstruction-of-counsel claims are “logically related” events that the court can regard as “arising out of the same transaction, occurrence or series of transactions or occurrences.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 20(a); Pls.’ Reply at 10 (quoting Mosley, 497 F.2d at 1333). In *142citing to Mosley, the plaintiffs assert that “all ‘logically related’ events entitling a person to institute a legal action against another generally are regarded as comprising a transaction or occurrence.” Mosley, 497 F.2d at 1330 (citing 7 C. Wright, Federal Practice & Procedure § 1653 at 270 (1972 ed.)); Pis.’ Reply at 15.

The court agrees with the plaintiffs’ assertion that “logically related” events may consist of an alleged “consistent pattern of ... obstruction of security-cleared counsel by [the] [defendants.” 2d Am. Compl. 11 430. Specifically, each of the existing plaintiffs allege that they were injured by the defendants through employment-related matters, such as retaliation, discrimination, and the denial of promotions and overseas assignments. 2d Am. Compl. ITU 36-37, 64-65, 129-30, 132-33, 140, 142,148-49, 154,156, 176-77, 190, 200, 209-12, 221, 224, 229-30, 232. After each employment dispute began, each of the plaintiffs or the plaintiffs’ counsel sought access to employee and agency records. Id. The defendants, however, denied and continue to deny the plaintiffs and/or their counsel access to the plaintiffs’ requested information. Id. As such, without this relevant information, the plaintiffs cannot effectively prepare or submit administrative complaints to the defendants or attempt to seek legal recourse through the applicable Title VII discrimination, Privacy Act, or First, Fifth, and Seventh Amendment claims. Id. The court concludes that the alleged repeated pattern of obstruction of counsel by the defendants against the plaintiffs is “logically related” as “a series of transactions or occurrences” that establishes an overall pattern of policies and practices aimed at denying effective assistance of counsel to the plaintiffs. Mosley, 497 F.2d at 1331,1333; Pis.’ Reply at 16. In this case, each plaintiff alleges that the defendants’ policy and practice of obstruction of counsel has damaged the plaintiffs. Id. Further, each plaintiff requests declaratory and injunctive relief. 2d Am. Compl. 11465. Thus, the court determines that each plaintiff in this case has satisfied the first prong of Rule 20(a). Fed. R. Civ. P. 20(a); see also Mosley, 497 F.2d at 1331, 1333.

Turning to the second prong of Rule 20(a), the plaintiffs aver that each of their claims are related by a common question of law or fact. FED. R. CIV. P. 20(a); Pis.’ Reply at 15. Specifically, one question of law or fact that is common to each of the six existing plaintiffs is whether the defendants’ September 4, 1998 notice restricting the plaintiffs’ counsel from accessing records intruded on the plaintiffs’ substantial interest in freely discussing their legal rights with their attorneys. Jacobs, 204 F.3d at 265 (quoting Martin, 686 F.2d at 32); 2d Am. Compl. ¶ 23. Indeed, the question of law or fact that is common to all may be whether the “defendants have engaged in a common scheme or pattern of behavior” that effectively denies the plaintiffs’ legal right to discuss their claims with their counsel. Fed. R. Civ. P. 20(a); In re Vitamins Antitrust Litig., 2000 WL 1475705, at 17, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7397, at *75-76; Brereton, 116 F.R.D. at 164. The plaintiffs also allege that the defendants’ policy or practice of obstruction of counsel “is implemented through [a] concert of action among CIA management and the Doe Defendants,” who are now named in the second amended complaint. Pis.’ Reply at 16; 2d Am. Compl. 1111547-52. In light of the aforementioned common questions of law and fact, the court concludes that the plaintiffs meet the second prong of Rule 20(a). Fed. R. Civ. P. 20(a).

The court need not stop here in its Rule 20(a) analysis. Indeed, it appears that there exists a further basis supporting the plaintiffs’ position challenging severance; Each plaintiff alleges common claims under the Privacy Act. Pis.’ Reply at 22. Specifically, the plaintiffs’ second amended complaint alleges that the defendants “maintained records about the plaintiffs in unauthorized systems of records in violation of § 552a(e)(4) of the Privacy Act” and that the defendants “failed to employ proper physical safeguards for records in violation of § 552a(e)(10) of the Privacy Act.” Id.; 2d Am. Compl. HH 472, 477. The plaintiffs also allege that the defendants wrongfully denied the plaintiffs and plaintiffs’ counsel access to records in violation of § 552a(d)(l) of the Privacy Act and “illegally maintained specific records describing their First Amendment activities in violation of § 552a(e)(7) of the Privacy Act.” 2d Am. *143Compl. 1111444, 489, 508-17; Pis.’ Reply at 22. Furthermore, the plaintiffs’ first amended complaint contains similar allegations. Through their alleged Privacy Act violations, the plaintiffs are united by yet another “question of law or fact” that is common to each of them. FED. R. CIV. P. 20(a). Accordingly, the court concludes that the plaintiffs satisfy the second prong of Rule 20(a) and, thus, the court denies the defendants’ motion to sever.

On a final note, in denying the defendants’ motion to sever, the court defers to the policy underlying Rule 20, which is to promote trial convenience, expedite the final determination of disputes, and prevent multiple lawsuits. Mosley, 497 F.2d at 1332. Indeed, the Supreme Court addressed this important policy in United Mine Workers of America v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715, 86 S.Ct. 1130, 16 L.Ed.2d 218 (1966), stating that “[ujnder the rules, the impulse is toward entertaining the broadest possible scope of action consistent with fairness to the parties; joinder of claims, parties, and remedies is strongly encouraged.” Id. at 724, 86 S.Ct. 1130. In accordance with Gibbs, the court believes that the joinder or non-severance of the six existing plaintiffs and their new claims under Rule 20(a) will promote trial convenience, expedite the final resolution of disputes, and act to prevent multiple lawsuits, extra expense to the parties, and loss of time to the court and the litigants in this case. Gibbs, 383 U.S. at 715, 86 S.Ct. 1130; Anderson, 291 F.Supp. at 711. For this added reason, the court denies the defendants’ motion to sever.

IV. CONCLUSION

For all of the foregoing reasons, the court grants the plaintiffs’ motion to amend and denies the defendants’ motion to sever. An order directing the parties in a manner consistent with this Memorandum Opinion is separately and contemporaneously issued this 30th day of July 2002.

ORDER

Granting the Plaintiffs’ Motion to Amend the Complaint; Denying the Defendants’ Motion to Sever

For the reasons stated in this court’s Memorandum Opinion separately and eon-temporaneously issued this 30th day of July 2002, it is

ORDERED that the plaintiffs’ motion for leave to file the second amended complaint is GRANTED; and it is

FURTHER ORDERED that the defendants’ motion to sever is DENIED; and it is

ORDERED that the defendants file a response to the plaintiffs’ second amended complaint within 60 days from the date of this order.

SO ORDERED.

11.5 Smuck v. Hobson 11.5 Smuck v. Hobson

Carl C. SMUCK, a Member of the Board of Education of the District of Columbia, Appellant, v. Julius W. HOBSON et al., Appellees. Carl F. HANSEN, Superintendent of Schools of the District of Columbia, Appellant, v. Julius W. HOBSON et al., Appellees.

Nos. 21167, 21168.

United States Court of Appeals District of Columbia Circuit.

Argued June 26, 1968.

Decided Jan. 21, 1969.

Danaher, Burger, and Tamm, Circuit Judges, dissented; McGowan, Circuit Judge, dissented in part.

*176Messrs. John L. Laskey and Edmund D. Campbell, Washington, D. C., with whom Messrs. F. Joseph Donohue and Thomas S. Jackson, Washington, D. C., were on the brief, for appellants.

Messrs. William M. Kunstler, New York City, and Richard J. Hopkins, with whom Mr. James O. Porter, Washington, D. G., was on the brief, for appellees. Mr. Jerry D. Anker, Washington, D. C., also entered an appearance for appellees.

Mr. E. Riley Casey, Washington, D. C., filed a brief on behalf of the National School Boards Association, as amicus curiae, urging reversal.

Mr. William B. Beebe, Washington, D. C., filed a brief on behalf of the American Association of School Administrators, as amicus curiae, urging reversal.

Messrs. Howard C. Westwood and Albert H. Kramer, Washington, D. C., filed a brief on behalf of the National Education Association, as amicus curiae, urging affirmance.

Messrs. J. Francis Pohlhaus and Frank D. Reeves, Washington, D. C., filed a brief on behalf of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, as amicus curiae, urging affirmance.

Before Bazelon, Chief Judge, and Danaher, Burger, McGowan, Tamm, Leventhal and Robinson, Circuit Judges, sitting en banc.

These appeals challenge the findings of the trial court that the Board of Education has in a variety of ways violated the Constitution in administering the District of Columbia schools.1 Among the facts that distinguish this case from the normal grist of appellate courts is the absence of the Board of Education as an appellant. Instead, the would-be appellants are Dr. Carl F. Hansen, the resigned superintendent of District schools, who appeals in his former official capacity and as an individual; Carl C. Smuck, a member of the Board of^. Education, who appeals in that capacity; and the parents of certain school children who have attempted to intervene in order to register on appeal their “dissent” from the order below.

*177The school board’s decision not to appeal inevitably adds a quality of artificiality to any proceedings in this Court. But the importance of the constitutional issues as stake requires an examination of whether these appellants should, despite the absence of the protagonist at trial, be given their day in a higher court. Moreover, our reluctance to review an order unchallenged by the principal defendant below is in some measure tempered by the fact that the present appointed school board has been superseded by a new Board of Education elected last fall.2 The most fundamental considerations demand that this new board should have the fullest discretion permitted by the Constitution to reshape educational policy within the District. This Court cannot ignore the importance of assuring that the new school board should not be strait jacketed by. an order not rooted in constitutional requirements. We conclude that the parents were prop-/ erly allowed to intervene of right in order to appeal those provisions of the decree which curtail the freedom of the school board to exercise its discretion in deciding upon educational policy.

Taking up the contentions advanced by the parents, our disposition is as follows: In Part II of this opinion we consider and reject certain procedural objections. In Part III we affirm on the merits those parts of the District Court’s decree that relate to pupil bussing, optional zones and faculty integration. In Part IV we conclude that the District Court’s rulings on the track system and on certain aspects of pupil assignment do not materially limit the discretion of the School Board, and that accordingly the parents lack standing to challenge the factual and legal bases underlying these provisions of the decree — a disposition that imports no view by this Court on the merits of the objections tendered by the parents on these issues.

I. Standing to Appeal

The Board of Education, as a corollary of its decision to accept the order below, directed Dr. Hansen not to appeal. Nevertheless, after his resignation was submitted and accepted by the board, Dr. Hansen noted his appeal as Superintendent of Schools. Whatever standing he might have possessed to appeal as a named defendant in the original suit, however, disappeared when Dr. Hansen left his official position.3 Presumably because he was aware of this, he subsequently moved to intervene under Rule 24(a) of the Rules of Civil Procedure in order to appeal as an individual. Although the trial judge found several reasons why such intervention should be denied, the motion was granted “in order to give the Court of Appeals an opportunity to pass on the intervention questions raised here * * *.”4 We agree with the reasoning of the trial court as to Dr. Hansen rather than with its result. The original decision was not a personal attack upon Dr. Hansen, nor did it bind him personally once he left office. And while it may or may not be true that but for the decision Dr. Hansen would still be Superintendent of Schools, the fact is that he did resign. He does not claim that a reversal or modification of the order by this Court would make his return to office likely. Consequently, the supposed impact of the decision upon his tenure is irrelevant insofar as an appeal is concerned, since a reversal would have no effect. Dr. Hansen thus has no “interest relating to the property or transaction which is the subject of the action” sufficient for Rule 24(a), and intervention is therefore unwarranted.

We also find that Mr. Smuck has no appealable interest as a member of the Board of Education. While he was in that capacity a named defendant, the *178Board of Education was undeniably the principal figure and could have been sued .alone as a collective entity. Appellant Smuck had a fair opportunity to participate in its defense, and in the decision not to appeal. Having done so, he has no separate interest as an individual in the litigation.5 The order directs the board to take certain actions. But since its decisions are made by vote as a collective whole, there is no apparent way in which Smuck as an individual could violate the decree and thereby become subject to enforcement proceedings.

The motion to intervene by the parents presents a more difficult problem requiring a correspondingly more detailed examination of the requirements for intervention of right. As amended in 1966, Rule 24(a) (2) permits such intervention

when the applicant claims an interest relating to the property or transaction which is the subject of the action and he is so situated that the disposition of the action may as a practical matter impair or impede his ability to protect that interest, unless the applicant’s interest is adequately represented by existing parties.

Before its recent amendment Rule 24 (a) contained two subdivisions requiring the petitioner to be “bound by a judgment in the action” or “so situated as to be adversely affected by a distribution or other disposition of property which is in the custody or subject to the control or disposition of the court or an officer thereof.” 6 As the trial judge pointed out in his decision to grant intervention to the parents, under the pre-amendment cases the task of defining what constitutes an “interest” was typically “subsumed in the questions of whether the petitioner would be bound or of what was the nature of his property interest.” 7 The 1966 amendments were designed to eliminate the scissoring effect whereby a petitioner who could show “inadequate representation” was thereby thrust against the blade that he would therefore not be “bound by a judgment,” and to recognize the decisions which had construed “property” so broadly as to make surplusage of the adjective.8 In doing so, the amendments made the question of what constitutes an “interest” more visible without contributing an answer. The phrasing of Rule 24(a) (2) as amended parallels that of Rule 19(a) (2) concerning joinder. But the fact that the two rules are entwined does not imply that an “interest” for the purpose of one is precisely the same as for the other.9 The occasions upon which a petitioner should be allowed to intervene under Rule 24 are not necessarily limited to those situations when the trial court should compel him to become a party under Rule 19. And while the division of Rule 24(a) and (b) into “Intervention of Right” and “Permissible Intervention” might superficially suggest that only the latter involves an exercise of discretion by the court, the contrary is clearly the case.10

The effort to extract substance from the conclusory phrase “interest” or “le-v gaily protectable interest” is of limited promise. Parents unquestionably have a sufficient “interest” in the education of their children to justify the initiation of a lawsuit in appropriate circumstances*17911, as indeed was the case for the plaintiff-appellee parents here. But in the context of intervention j the question is not whether a lawsuit should be begun, but whether already initiated litigation should be extended to include additional parties.) The 1966 amendments to Rule 24(a) have facilitated this, the true inquiry, by eliminating the temptation or need for tangential expeditions in search of “property” or someone “bound by a judgment.” It would be unfortunate to allow the inquiry to be led once again astray by a myopic fixation upon “interest.” Rather, as Judge Leventhal recently concluded for this Court, “[A] more instructive approach is to let our construction be guided by the policies behind the ‘interest’ requirement. * * * [T]he ‘interest’ test is primarily a practical guide to disposing of lawsuits by involving as many apparently concerned persons as is compatible with efficiency and due process.”12

The decision^ whether intervention of right is warranted thus involves an accommodation between two potentially conflicting goalsjJ~"lo achieve judicial v economies of scale by resolving related issues in a single lawsuit, ándito prevent the single lawsuit from becoming fruitlessly complex or unending. Since this •task will depend upon the contours of the particular controversy, general rules and past decisions cannot provide uni-'' formly dependable guides.13 The Supreme Court, in its only full-dress examination of Rule 24(a) since the 1966 amendments, found that a gas distributor was entitled to intervention of right although its only “interest” was the economic harm it claimed would follow from an allegedly inadequate plan for divestiture approved by the Government in an antitrust proceeding.14 While conceding that the Court’s opinion granting intervention in Cascade Natural Gas Corp. v. El Paso Natural Gas Co. “is certainly susceptible of a very-, broad reading,” the trial judge here would distinguish the decision on the ground that the petitioner “did show a strong, direct economic interest, for the new company [to be created by divestiture] would be its sole supplier.”15 Yet while it is undoubtedly true that “Cascade should not be read as a carte blanche for intervention by anyone at any time,” 16 there is no apparent reason why an “economic interest” should always be necessary to justify intervention. The goal of “disposing of lawsuits by involving as many apparently concerned persons as is compatible with efficiency and due process” may in certain circumstances be met by allowing parents whose only “interest” is the education of their children to intervene. In determining whether such circumstances are present, the first requirement of Rule 24(a) (2), that of an “interest” in the transaction, may be a less useful point of departure than the second and third requirements, that the applicant may be impeded in protecting his interest by the action and that his interest is not adequately represented by others.

This does not imply that the need for an “interest” in the controversy should or can be read out of the rule. But the requirement should be viewed as a prerequisite rather than relied upon as a determinative criterion for intervention. *180«'If barriers are needed to limit extension of the right to intervene, the criteria , of practical harm to the applicant and the adequacy of representation by others are better suited to the task. If those requirements are met, the nature of his “interest” may play a role in determining the sort of intervention which should be allowed — whether, for example, he should be permitted to contest all issues, and whether he should enjoy all the prerogatives of a party litigant.17

Both courts and legislatures have recognized as appropriate the concern for their children’s welfare which the parents here seek to protect by intervention.18 While the artificiality of an appeal without the Board of Education cannot be ignored, neither can the importance of the constitutional issues decided below. The relevance of substantial and unsettled questions of law has been recognized in allowing intervention to perfect an appeal.19 And this Court has noted repeatedly, “obviously tailored to fit ordinary civil litigation, [the provisions of Rule 24] require other than literal application in atypical cases.”20 We conclude that the interests asserted by the intervenors are sufficient to justify an examination of whether the two remaining requirements for intervention are met.

Rule 24(a) as amended requires not that the applicant would be “bound” by a judgment in the action, but only that “disposition of the action may as a practical matter impair or impede his ability to protect that interest.” In Nuesse v. Camp21 this Court examined a motion by a state commissioner of banks to intervene under the new Rule 24(a) in a suit brought by a state bank against the United States Comptroller of Currency. The plaintiff claimed that the defendant would violate the National Bank Act22 if he approved the application of a national bank to open a new branch near the plaintiff’s office. The intervenor feared an interpretation of the statute which would stand as precedent in any later litigation he might initiate. The Court, agreeing, concluded that “under this new test stare decisis principles may in some cases supply the practical disadvantage that warrants intervention as of right.”23 But if a decision interpreting a statute against the applicant’s contentions would so handicap him in pursuing a subsequent lawsuit as to justify intervention, the appellants in this case would face a hopeless task in a later suit. The intervening parents assert that the Board of Education should be free tp make policy decisions concerning such matters as pupil and faculty assignments without the constraints imposed by the decision below. If allowed to intervene, they hope to show that the past practices condemned by the trial court did not violate the Constitution and hence that the decree should be vacated. Should succeed, the Board of Education wiHrl.fpfv' deed be freed of certain constraints upon its exercise of discretion in establishing educational policy. But if the right to intervene is denied and the decision below becomes final, there is no apparent way for the parents to pursue their in*181terests in a subsequent lawsuit. True, they could assert that the new policies adopted by the Board of Education in compliance with the order below are unconstitutional. But this would be a sterner. challenge than they would face as intervenors here,: although the new policies might not be constitutionally required, they might also not be unconstitutional. Indeed, the very premise for the intervenors’ attack on the trial court decision is that school authorities can exercise wide discretion without encountering affirmative constitutional duties or negative prohibitions. While the scope of this discretion is uncertain, its existence is not: some policies may be constitutionally permissible, and hence immune to attack in a fresh lawsuit, which are not constitutionally required. Since this is so, the intervenors have borne their burden to show that their interests would “as a practical matter” be affected by a final disposition of this case without appeal.

The remaining requirement for intervention is that the applicant not be adequately represented by others. No question is raised here but that the Board of Education adequately represented the intervenors at the trial below; the issue rather whether the parents were '■fMPguately represented by the school decision not to appeal. The presumed good faith of the board in reaching this decision is not conclusive. “[B]ad faith is not always a prerequisite to intervention,” 24 nor is it necessary that the interests of the intervenor and his putative champion already a party be “wholly ‘adverse.’ ” 25 As the conditional wording of Rule 24(a) (2) suggests in permitting intervention “unless the applicant’s interest is adequately represented by existing parties,” “the burden [is] on those opposing intervention to show the adequacy of the existing representation.” 26 In this case, the interests of the parents who wish to intervene in order to appeal do not coincide with those of the Board of Education. The school board represents all parents within the District. The intervening appellants may have more parochial interests centering upon the education of their own children. While they cannot of course ask the Board to favor their children unconstitutionally at the expense of others, they like other parents can seek the adoption of policies beneficial to their own children. Moreover, considerations of publicity, cost, and delay may not have the same weight for the parents as for the school board in the context of a decision to appeal. And the Board of Education, buffeted as it like other school boards is by conflicting public demands, may possibly have less interest in preserving its own untrammeled discretion than do the parents. It is not necessary to accuse the board of bad faith in deciding not to appeal or of a lack of vigor in defending the suit below in order to recognize that a restrictive court order may be a not wholly unwelcome haven.

The question of adequate representation when a motion is made for intervention to appeal is related to the question of whether the motion is timely. To a degree it may well be true that a “strong showing” is required to justify intervention after judgment.27 But by the same token a failure to appeal may be one factor in deciding whether representation by existing parties is adequate.28 As the opinion of the trial court in granting intervention demon*182strates, the leading cases in which intervention has been permitted following a judgment tend to involve unique situations.29 The very absence of any precedent involving the same or even closely analogous facts requires a close examination of all the circumstances of this case. We conclude that the inter-venor-appellants here have shown a sufficiently serious possibility that they were not adequately represented in the decision not to appeal.

Our holding that the appellants would be practically disadvantaged by a decision without appeal in this case and that they are not otherwise adequately represented necessitates a closer scrutiny of the precise nature of their interest and the scope of intervention that should accordingly be granted. The parents who seek to appeal do not come before this court to protect the good name of the Board of Education. Their interest is not to protect the board, or Dr. Hansen, from an unfair finding. Their asserted interest is rather the freedom of the school board — and particularly the new school board recently elected30 — to exercise the broadest discretion constitutionally permissible in deciding upon educational policies. Since this is so, their interest extends only to those parts of the order which can fairly be said to impose restraints upon the Board of Education. And because the school board is not a party to this appeal, review should be limited to those features of the order which limit the discretion of the old or new board.

II. Procedural Issues