1 Unit A: The Fight to Exclude Expert Testimony on Forensic Evidence 1 Unit A: The Fight to Exclude Expert Testimony on Forensic Evidence

1.1 Class 1: Overview- Junk Science 1.1 Class 1: Overview- Junk Science

Video Explaining how to use our H20 and Moodle sites

5 min

(If you have used H20 and Moodle before you do not need to watch this video.)

Enroll in our Moodle course

Please use this link to enroll in our course on Moodle, the second of our two online platforms.

IF YOU ARE NEW TO MOODLE:

Step 1: Create an account on Moodle

When you open the link you should see text below the login field that asks: “Is this your first time here?”

Click on the “Create a new account” button below that question.

When creating your account you need to use your CUNY Law email address.

Step 2: Confirm your account or wait for me to confirm your account

One of two things will happen next: (1) within ten minutes of registering you may email that gives you instructions for confirming your account - if you get that email, please click on the included link and move to step 3. (2) If you do not recieve an email in 10 minutes, please just email me and let me know that you registered. I will then confirm your account and email you back to let you know it is confirmed. Once you hear back from me, please go to step 3.

Step 3: Enroll in our course

When you click to confirm your account, or log on to moodle.cuny.law.edu after your account is confirmed, please select the “site home” option on the left hand menu.

Then select our course from the list of “available courses”

Click on the blue icon that says “Enroll in course.” You should now see the content that I referenced in the video.

IF YOU HAVE PREVIOUSLY ENROLLED IN MOODLE:

Please select the “site home” option on the left hand menu.

Then select our course from the list of “available courses”

Click on the blue icon that says “Enroll in course.” You should now see the content that I referenced in the video.

Part 1: Advanced Evidence Intro Survey

Please use this link to complete the short introductory survey. Please complete the survey by 9:00 a.m. on Monday, January 22.

Part 2: Advanced Evidence Intro Survey

Please go to the link below and complete the anonymous portion of the introductory survey by 9:00 a.m. on Monday, January 22.

Forensic Science: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO)

Please watch this 19 minute clip from the John Oliver show on forensic science. (Be warned: it is filled with profanity and some bad puns.).

Training Officers to Shoot First, and He Will Answer Questions Later Training Officers to Shoot First, and He Will Answer Questions Later

Matt Apuzzo, The New York Times (Aug. 1, 2015) (Kitty Bennett contributed research)

This article uses a painful and perpetually timely topic (police shootings of civilians and the failure of the legal system to impose consequences) to illustrate the broader problem of admitting expert testimony that may lack a sufficient scientific basis.

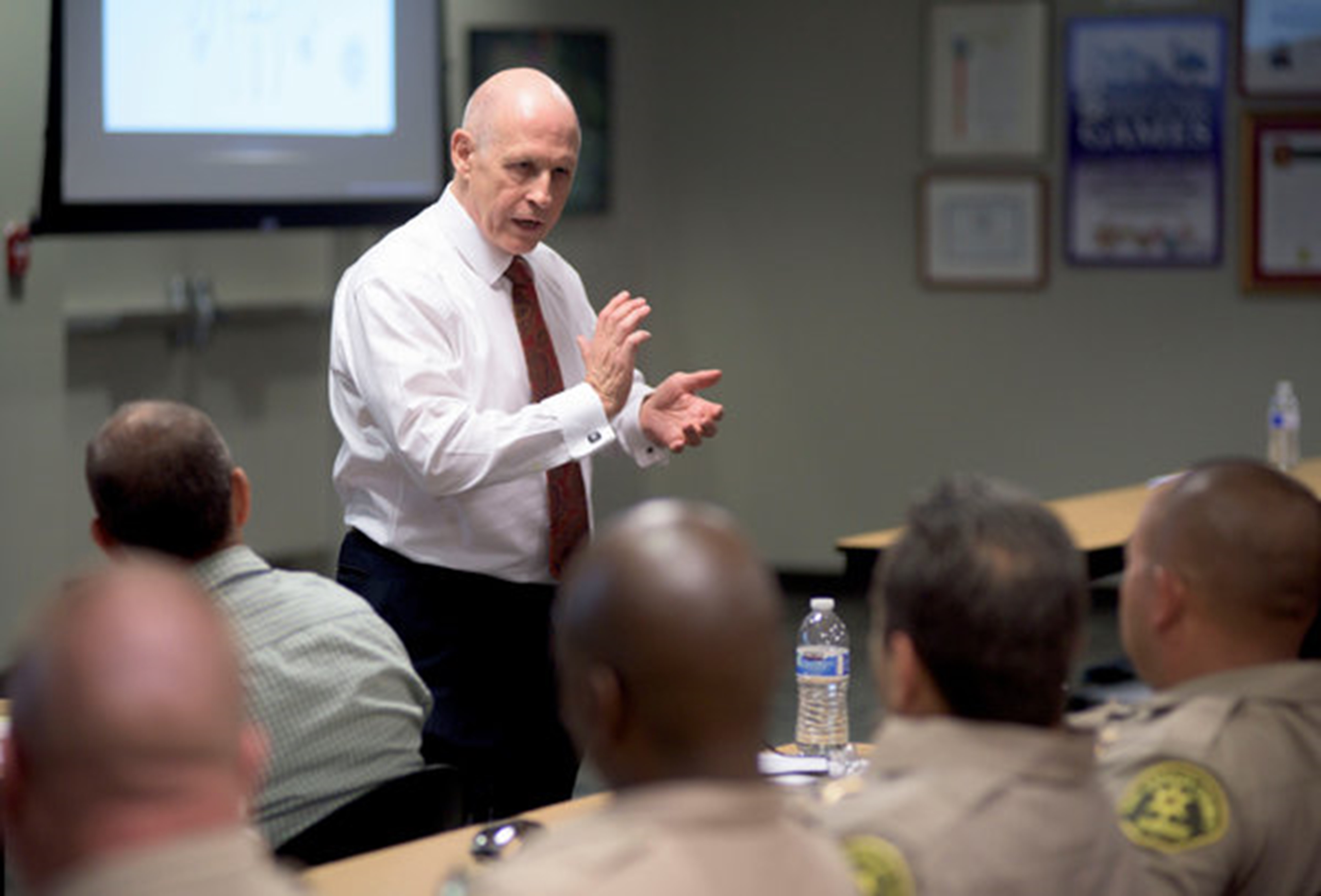

William J. Lewinski, a psychologist who has studied police shootings, held a training session at the Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs in Monterey Park, Calif., last month. Credit Michal Czerwonka for The New York Times

WASHINGTON — The shooting looked bad. But that is when the professor is at his best. A black motorist, pulled to the side of the road for a turn-signal violation, had stuffed his hand into his pocket. The white officer yelled for him to take it out. When the driver started to comply, the officer shot him dead.

The driver was unarmed.

Taking the stand at a public inquest, William J. Lewinski, the psychology professor, explained that the officer had no choice but to act.

“In simple terms,” the district attorney in Portland, Ore., asked, “if I see the gun, I’m dead?”

“In simple terms, that’s it,” Dr. Lewinski replied.

When police officers shoot people under questionable circumstances, Dr. Lewinski is often there to defend their actions. Among the most influential voices on the subject, he has testified in or consulted in nearly 200 cases over the last decade or so and has helped justify countless shootings around the country.

His conclusions are consistent: The officer acted appropriately, even when shooting an unarmed person. Even when shooting someone in the back. Even when witness testimony, forensic evidence or video footage contradicts the officer’s story.

He has appeared as an expert witness in criminal trials, civil cases and disciplinary hearings, and before grand juries, where such testimony is given in secret and goes unchallenged. In addition, his company, the Force Science Institute, has trained tens of thousands of police officers on how to think differently about police shootings that might appear excessive.

A string of deadly police encounters in Ferguson, Mo.; North Charleston, S.C.; and most recently in Cincinnati, has prompted a national reconsideration of how officers use force and provoked calls for them to slow down and defuse conflicts. But the debate has also left many police officers feeling unfairly maligned and suspicious of new policies that they say could put them at risk. Dr. Lewinski says his research clearly shows that officers often cannot wait to act.

“We’re telling officers, ‘Look for cover and then read the threat,’ ” he told a class of Los Angeles County deputy sheriffs recently. “Sorry, too damn late.”

A former Minnesota State professor, he says his testimony and training are based on hard science, but his research has been roundly criticized by experts. An editor for The American Journal of Psychology called his work “pseudoscience.” The Justice Department denounced his findings as “lacking in both foundation and reliability.” Civil rights lawyers say he is selling dangerous ideas.

An Expert on the Stand

While his testimony at times has proved insufficient to persuade a jury, his record includes many high-profile wins.

“He won’t give an inch on cross-examination,” said Elden Rosenthal, a lawyer who represented the family of James Jahar Perez, the man killed in the 2004 Portland shooting. In that case, Dr. Lewinski also testified before the grand jury, which brought no charges. Defense lawyers like Dr. Lewinski, Mr. Rosenthal said. “They know that he’s battle-hardened in the courtroom, so you know exactly what you’re getting.”

Dr. Lewinski, 70, is affable and confident in his research, but not so polished as to sound like a salesman. In testimony on the stand, for which he charges nearly $1,000 an hour, he offers winding answers to questions and seldom appears flustered. He sprinkles scientific explanations with sports analogies.

“A batter can’t wait for a ball to cross home plate before deciding whether that’s something to swing at,” he told the Los Angeles deputy sheriffs. “Make sense? Officers have to make a prediction based on cues.”

Of course, it follows that batters will sometimes swing at bad pitches, and that officers will sometimes shoot unarmed people.

Much of the criticism of his work, Dr. Lewinski said, amounts to politics. In 2012, for example, just seven months after the Justice Department excoriated him and his methods, department officials paid him $55,000 to help defend a federal drug agent who shot and killed an unarmed 18-year-old in California. Then last year, as part of a settlement over excessive force in the Seattle Police Department, the Justice Department endorsed sending officers to Mr. Lewinski for training. And in January, he was paid $15,000 to train federal marshals.

If the science is there, Dr. Lewinski said, he does not shy away from offering opinions in controversial cases. He said he was working on behalf of one of two Albuquerque officers who face murder charges in last year’s shooting death of a mentally ill homeless man. He has testified in many racially charged cases involving white officers who shot black suspects, such as the 2009 case in which a Bay Area transit officer shot and killed Oscar Grant, an unarmed black man, at close range.

Dr. Lewinski said he was not trying to explain away every shooting. But when he testifies, it is almost always in defense of police shootings. Officers are his target audience — he publishes a newsletter on police use of force that he says has nearly one million subscribers — and his research was devised for them. “The science is based on trying to keep officers safe,” he said.

Dr. Lewinski, who grew up in Canada, got his doctorate in 1988 from the Union for Experimenting Colleges and Universities, an accredited but alternative Cincinnati school offering accelerated programs and flexible schedules. He designed his curriculum and named his program police psychology, a specialty not available elsewhere.

‘Invalid and Unreliable’

In 1990, a police shooting in Minneapolis changed the course of his career. Dan May, a white police officer, shot and killed Tycel Nelson, a black 17-year-old. Officer May said he fired after the teenager turned toward him and raised a handgun. But an autopsy showed he was shot in the back.

Dr. Lewinski was intrigued by the apparent contradiction. “We really need to get into the dynamics of how this unfolds,” he remembers thinking. “We need a lot better research.”

He began by videotaping students as they raised handguns and then quickly turned their backs. On average, that move took about half a second. By the time an officer returned fire, Dr. Lewinski concluded, a suspect could have turned his back.

He summarized his findings in 1999 in The Police Marksman, a popular magazine for officers. The next year, it published an expanded study, in which Dr. Lewinski timed students as they fired while turning, running or sitting with a gun at their side, as if stashed in a car’s console.

Suspects, he concluded, could reach, fire and move remarkably fast. But faster than an officer could react? In 2002, a third study concluded that it takes the average officer about a second and a half to draw from a holster, aim and fire.

Together, the studies appeared to support the idea that officers were at a serious disadvantage. The studies are the foundation for much of his work over the past decade.

Because he published in a police magazine and not a scientific journal, Dr. Lewinski was not subjected to the peer-review process. But in separate cases in 2011 and 2012, the Justice Department and a private lawyer asked Lisa Fournier, a Washington State University professor and an American Journal of Psychology editor, to review Dr. Lewinski’s studies. She said they lacked basic elements of legitimate research, such as control groups, and drew conclusions that were unsupported by the data.

“In summary, this study is invalid and unreliable,” she wrote in court documents in 2012. “In my opinion, this study questions the ability of Mr. Lewinski to apply relevant and reliable data to answer a question or support an argument.”

Dr. Lewinski said he chose to publish his findings in the magazine because it reached so many officers who would never read a scientific journal. If he were doing it over, he said in an interview, he would have published his early studies in academic journals and summarized them elsewhere for officers. But he said it was unfair for Dr. Fournier to criticize his research based on summaries written for a general audience.While opposing lawyers and experts found his research controversial, they were particularly frustrated by Dr. Lewinski’s tendency to get inside people’s heads. Time and again, his reports to defense lawyers seem to make conclusive statements about what officers saw, what they did not, and what they cannot remember.

Often, these details are hotly disputed. For example, in a 2009 case that revolved around whether a Texas sheriff’s deputy felt threatened by a car coming at him, Dr. Lewinski said that the officer was so focused on firing to stop the threat, he did not immediately recognize that the car had passed him.

Inattentional Blindness

Such gaps in observation and memory, he says, can be explained by a phenomenon called inattentional blindness, in which the brain is so focused on one task that it blocks out everything else. When an officer’s version of events is disproved by video or forensic evidence, Dr. Lewinski says, inattentional blindness may be to blame. It is human nature, he says, to try to fill in the blanks.

“Whenever the cop says something that’s helpful, it’s as good as gold,” said Mr. Burton, the California lawyer. “But when a cop says something that’s inconvenient, it’s a result of this memory loss.”

Experts say Dr. Lewinski is too sure of himself on the subject. “I hate the fact that it’s being used in this way,” said Arien Mack, one of two psychologists who coined the term inattentional blindness. “When we work in a lab, we ask them if they saw something. They have no motivation to lie. A police officer involved in a shooting certainly has a reason to lie.”

Dr. Lewinski acknowledged that there was no clear way to distinguish inattentional blindness from lying. He said he had tried to present it as a possibility, not a conclusion.

Almost as soon as his research was published, lawyers took notice and asked him to explain his work to juries.

In Los Angeles, he helped authorities explain the still-controversial fatal shooting of Anthony Dwain Lee, a Hollywood actor who was shot through a window by a police officer at a Halloween party in 2000. The actor carried a fake gun as part of his costume. Mr. Lee was shot several times in the back. The officer was not charged.

The city settled a lawsuit over the shooting for $225,000, but Mr. Lewinski still teaches the case as an example of a justified shooting that unfairly tarnished a good officer who “was shooting to save his own life.”

In September 2001, a Cincinnati judge acquitted a police officer, Stephen Roach, in the shooting death of an unarmed black man after a chase. The officer said he believed the man, Timothy Thomas, 19, was reaching for a gun. Dr. Lewinski testified, and the judge said he found his analysis credible. The prosecutor, Stephen McIntosh, however, told The Columbus Dispatch that Dr. Lewinski’s “radical” views could be used to justify nearly any police shooting.

“If that’s the sort of direction we, as a society, are going,” the prosecutor said, “I have a lot of disappointment.” Since then, Dr. Lewinski has testified in many dozens of cases in state and federal court, becoming a hero to many officers who feel that politics, not science or safety, drives police policy. For example, departments often require officers to consider less-lethal options such as pepper spray, stun guns and beanbag guns before drawing their firearms.

“These have come about because of political pressure,” said Les Robbins, the executive director of the Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs. In an interview, Mr. Robbins recalled how he used to keep his gun drawn and hidden behind his leg during most traffic stops. “We used to be able to use the baton and hit people where we felt necessary to get them to comply. Those days are gone.”

Positions of Authority

Dr. Lewinski and his company have provided training for dozens of departments, including in Cincinnati, Las Vegas, Milwaukee and Seattle. His messages often conflict, in both substance and tone, with the training now recommended by the Justice Department and police organizations.

The Police Executive Research Forum, a group that counts most major city police chiefs as members, has called for greater restraint from officers and slower, better decision making. Chuck Wexler, its director, said he is troubled by Dr. Lewinski’s teachings. He added that even as chiefs changed their use-of-force policies, many did not know what their officers were taught in academies and private sessions.

“It’s not that chiefs don’t care,” he said. “It’s rare that a chief has time to sit at the academy and see what’s being taught.”

Regardless of what, if any, policy changes emerge from the current national debate, civil right lawyers say one thing will not change: Jurors want to believe police officers, and Dr. Lewinski’s research tells them that they can.

On a cold night in early 2003, for instance, Robert Murtha, an officer in Hartford, Conn., shot three times at the driver of a car. He said the vehicle had sped directly at him, knocking him to the ground as he fired. Video from a nearby police cruiser told another story. The officer had not been struck. He had fired through the driver’s-side window as the car passed him.

Officer Murtha’s story was so obviously incorrect that he was arrested on charges of assault and fabricating evidence. If officers can get away with shooting people and lying about it, the prosecutor declared, “the system is doomed.”

“There was no way around it — Murtha was dead wrong,” his lawyer, Hugh F. Keefe, recalled recently. But the officer was “bright, articulate and truthful,” Mr. Keefe said. Jurors needed an explanation for how the officer could be so wrong and still be innocent.

Dr. Lewinski testified at trial. The jury deliberated less than one full day. The officer was acquitted of all charges.

Criminal Law 2.0 ("reasons to doubt that our criminal justice system is fundamentally just”)

HON. ALEX KOZINSKI, 44 GEO. L.J. ANN. REV. CRIM. PROC (2015)

Please read the first 10.5 pages (pages iii - xiii) where Judge Kozinski describes 12 "reasons to doubt that our criminal justice system is fundamentally just.” (You do not need to read the footnotes.) Note that the first six reasons are forensic evidence issues.

(Note: Judge Kozinski has since retired in response to multiple accusations of sexual harassment.)

Forensic Science in Criminal Courts: Ensuring Scientific Validity of Feature-Comparison Methods

Report to the President, President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) Sept. 2016

Please read the Introduction at pages 21-24.

“Forensic Science Isn’t Science”

Mark Joseph Stern, Slate (June 11, 2014)

This article provides a short, accessible summary of the conclusions of the 2009 NRC report which is referenced on page 22 of the PCAST report.

The status quo is . . .

by Chris Fabricant of The Innocence Project

This 30 second clip provides a summary of the problem with junk science by Chris Fabricant, an attorney with the Innocence Project.

The Entrenched Carceralism of Forensics

By Maneka Sinha, Inquest (July 26, 2021)

Professor Sinha documents the forensic system’s carceral origins, identifies structural impediments to reform, and suggests we look beyond conventional or “reformist” reforms to seek radical, transformative change.

Exoneree Voices: The human toll of wrongful convictions

This 3 minute video was made as part of fundraising/public education message for the New England Innocence Project but I wanted to include it beacuse it allows us to hear directly from people impacted by wrongful convictions.

Writing Reflection #1 Writing Reflection #1

Please go to our Moodle Page and under "Class 1" you will find the prompt and submission folder for Writing Reflection #1.

1.2 Class 2: Context - Racism 1.2 Class 2: Context - Racism

Read the Course Syllabus Read the Course Syllabus

Please read the course syllabus that is posted on Moodle.

20 second quote from Chris Fabricant

Chris Fabricant is the Director of Strategic Ligation for the Innocence Project.

Excerpt from Radically Reimagining Forensic Evidence Excerpt from Radically Reimagining Forensic Evidence

Maneka Sinha, Radically Reimagining Forensic Evidence, 73 Alabama Law Review 879 (2022)

This excerpt provides some important information on the roots and purpose of forensic analysis in criminal cases. Professor Sinha is a Professor at the University of Maryland School of Law and was previously the head of the Forensic Practice Group at the Public Defender Service of D.C.

Forensic methods enable surveillance, prosecution, conviction, and punishment, the core inputs and outputs of the criminal legal system.[1] Black, Brown, and other marginalized groups, overrepresented in the criminal legal system, are especially impacted by these methods. Forensic techniques allow law enforcement to surveil and monitor: DNA and fingerprint databases, in which Black and Brown people are overrepresented, house identifying information of millions of individuals and allow police to monitor and supervise communities;[2] police use, often in secret, sophisticated location tracking devices to surveil; and emerging technologies, like facial recognition systems, allow even greater mass monitoring and surveillance.[3] Databases like the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), the Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS), and even consumer DNA databases amass biometric data in seeming perpetuity, widening law enforcement’s net of possible suspects.[4] Unsurprisingly, people of color, and Black people especially, are most affected by these tactics, as law enforcement monitors their communities more than those of other, non-marginalized populations.[5] Not only do forensic methods enable carceral harm, they also launder and legitimize it by cloaking carceral functions with the allegedly neutral and objective aura of “science.”[6]

. . .

1. The Carceral Origins of Forensic Methods

“[M]any forensic fields (e.g., firearms analysis, latent fingerprint identification) are but handmaidens of the legal system, and they have no significant uses beyond law enforcement.”[7]

* * *

. . .

Most forensic methods were first developed in police departments as investigative aids meant to produce evidence that would connect suspects to crimes and secure convictions.[8] Despite the nomenclature, other than DNA analysis, the forensic sciences did not arise out of academia, research institutions or scientific laboratories—they do not have their origins in the sciences at all.[9] Their development was financed by the “War on Crime,” launched by President Lyndon Johnson in 1965, and the better-known “War on Drugs,” which brought federal funding to local police departments to effectuate national crime policy.

In the mid-1960s, partially in response to unrest in urban cities related to discriminatory policing, mass fear around rising crime took hold across America and in national politics.[10] As part of a federal response to the perceived threat of crime and disorder, in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson launched the “War on Crime”—the less famous precursor to President Nixon and Reagan’s “War on Drugs”—and sent Congress the Law Enforcement Assistance Act.[11] The passage of the Law Enforcement Assistance Act was a watershed moment in American law enforcement; it marked the beginning of the modern era of criminal justice in which the federal government plays a direct role in local law enforcement.[12]

The Law Enforcement Assistance Act paved the way not only for mass criminalization, but also for the widespread use of forensic methods in law enforcement seen today.[13] In the leadup to the passage of the Law Enforcement Act, President Johnson established a national commission to study the perceived crime problem and develop a national law enforcement program.[14] The commission focused its efforts on urban Black communities, which it believed to be at the center of the crime problem, without consultation with members of those communities.[15]

The commission’s sweeping final report, issued in 1967, made hundreds of wide-ranging recommendations.[16] Among these were recommendations to improve police ability to utilize technological advancements like fingerprint and voiceprint analysis and other forensic techniques by establishing additional crime labs and conducting research to facilitate the use of such techniques to aid in law enforcement efforts.[17] The commission also suggested that future crime solving would require collection and forensic analysis of physical crime scene evidence, including fingerprints, weapons, shoeprints, and trace evidence, and encouraged investment in lab services and the establishment of a central fingerprint database.[18]

These recommendations were a significant factor in paving the way for increased attention to the development and utilization of forensic methods.[19] The commission’s recommendations became the basis for legislation that provided unprecedented funding to local law enforcement agencies to facilitate these new initiatives.[20] Billions of dollars were ultimately sent to local law enforcement, which allowed the development of methods to collect and analyze physical crime scene evidence and resulted in the proliferation of police crime labs.[21] Notably, War on Crime dollars also went to funding of surveillance technologies focusing on Black communities that included helicopter systems, crime prediction programs, and mobile surveillance units.[22]

. . .

As a result of its law enforcement origins, forensic disciplines have a natural alignment with one side of the adversarial process: the prosecution.[23] That alignment runs deep.[24] Forensic practitioners both work for and communicate heavily with prosecutors and rarely work collaboratively with defense lawyers without prosecutors listening in.[25] As a result, forensic practitioners often see themselves as part of the prosecution team, exhibiting pro-prosecution bias and willingness to provide testimony that supports the prosecution’s case, even when unwarranted.[26] Even those who do not view themselves as an arm of law enforcement may be pressured to return the result sought by the prosecution.[27]

Though most forensic methods were developed outside the scientific process without integrating fundamentals of the scientific method, law enforcement coopted the term “science” as part of a strategy to professionalize police departments by connecting them to science and to lend weight and credibility to forensic techniques.[28] Practitioners described themselves as forensic “scientists,” when they are often more aptly characterized as technicians, who focus on the application of methods rather than research or theory.[29] Police departments created crime laboratories not for testing theories and hypotheses, but at least in part for public relations.[30]

Because forensics inherited law enforcement’s concern for securing convictions, the scientific method and process were often left by the wayside in the development of forensic methods.[31] Given that those targeted for prosecution and conviction are disproportionately Black, Brown, or otherwise of color,[32] it comes as no surprise that those convicted by unreliable forensic evidence are also members of marginalized communities. The overlap between the increased use of forensic techniques and the mass expansion of the criminal legal system makes clear that those who have been hit hardest by nearly five decades of expanded criminalization, Black and Brown communities,[33] are also the most likely to bear the brunt of flawed forensics in their cases. It is difficult to quantify the effects of flawed forensics, but the available data bear this out. The National Registry of Exonerations reports that problematic forensic evidence has contributed to twenty-four percent of wrongful convictions.[34] Of that group, fifty-four percent of those convicted are Black or Latinx.[35]

. . .

Footnotes:

[1] See Mnookin et al., supra note 116, at 726.

[2] See Ava Kofman, The FBI Wants to Exempt Massive Biometric Database from the Privacy Act, The Intercept (June 1, 2016), https://theintercept.com/2016/06/01/the-fbi-wants-to-exempt-massive-biometric-database-from-the-privacy-act/; Natalie Ram, The U.S. May Soon Have a De Facto National DNA Database, Slate (Mar. 19, 2019), https://slate.com/technology/2019/03/national-dna-database-law-enforcement-genetic-genealogy.html; Privacy Impact Assessment Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System National Security Enhancements, FBI (last visited Mar. 5, 2021), https://www.fbi.gov/services/information-management/foipa/privacy-impact-assessments/iafis; Erin Murphy & Jun H. Tong, The Racial Composition of Forensic DNA Databases, 108 Calif. L. Rev. 1847, 1851 (2020); Denise Syndercombe Court, Protecting against racial bias in DNA databasing, 1 Nature Computational Sci. 249, 249 (2021).

[3] Lindsey Barret, Ban Facial Recognition Technologies for Children and for Anyone Else, 26 B.U. J. Sci. & Tech. 223, 240 (2020); Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, Facial Recognition and the Fourth Amendment, 105 Minn. L. Rev. 1105, 1112 (2021).

[4] Natalie Ram, Erin Murphy & Sonia Suter, Regulating forensic genetic genealogy, 373 Science 1444, 1444 (2021).

[5] See Murphy & Tong, supra note 82, at 1851.

[6] See Cino, supra note 126, at 540 (“[E]veryone can sleep better at night because ‘science’ solidified the conviction.”).

[7] NAS Report, supra note 2, at 52.

[8] See NAS Report, supra note 2, at 42, 187; Meehan Crist & Tim Requarth, Forensic Science Put Jimmy Genrich in Prison for 24 Years. What if It Wasn’t Science?: A Special Investigation Reveals a Disastrous Flaw Affecting Thousands of Criminal Convictions, The Nation (Feb. 1, 2018), https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/the-crisis-of-american-forensics/; Terrence F. Kiely, The Houses of Deceits: Science, Forensic Science, and Evidence and Introduction to Forensic Evidence, 35 Land & Water L. Rev. 397, 415 (2000).

[9] Eric S. Lander, Fixing Rule 702: The PCAST Report and Steps to Ensure the Reliability of Forensic Feature-Comparison Methods in the Criminal Courts, 86 Fordham L. Rev. 1661, 1668 (2018); Paul C. Giannelli, Independent Crime Laboratories: The Problem of Motivational and Cognitive Bias, 2010 Utah L. Rev. 247, 250; NAS Report, supra note 2, at 42; Sandra Guerra Thompson, Cops in Lab Coats: Curbing Wrongful Convictions through Independent Forensic Laboratories 195 (2015); Radley Balko, Opinion, Jeff Sessions Wants to Keep Forensics in the Dark Ages, Wash. Post (Apr. 11, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-watch/wp/2017/04/11/jeff-sessions-wants-to-keep-forensics-in-the-dark-ages/.

[10] See Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America 6, 55-56 (2016). In reality, and contrary to popular belief, reported rising crime rates corresponded to newly-implemented crime statistics measures and reporting policies that coincided with new federal crime control funding tied to reported crime rates. Id.

[11] Id. at 6, 56

[12] Id. at 1-2.

[13] Id. at 5; Joseph L. Peterson & Anna S. Leggett, The Evolution of Forensic Science: Progress Amid the Pitfalls, 36 Stetson L. Rev. 621, 623-25 (2007).

[14] President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society, U.S. Gov’t Printing Off., Foreword (1967) [hereinafter Crime Commission Report], https://www.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh241/files/archives/ncjrs/42.pdf; Hinton, supra note 91, at 80-81.

[15] Id. at 83-83.

[16] Crime Commission Report, supra note 95, at 293-301.

[17] Id. at 245-46, 255.

[18] President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, Task Force On the Police, Task Force Report: The Police, U.S. Gov’t Printing Off., 51, 57, 92 (1967), https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/147374NCJRS.pdf.

[19] Id. at 92.

[20] Hinton, supra note 91, at 2, 104; Peterson & Leggett, supra note 94, at 623.

[21] Peterson & Leggett, supra note 94, at 625.

[22] Hinton, supra note 91, at 87, 90-92.

[23] Michael J. Saks, Merlin and Solomon: Lessons from the Law’s Formative Encounters with Forensic Identification Science, 49 Hastings L.J. 1069, 1092 (1998).

[24] Id.

[25] See Nicole Bremner Cásarez & Sandra Guerra Thompson, Three Transformative Ideals to Build a Better Crime Lab, 34 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. 1007, 1008 (2018). Of course, the accused use forensic evidence too, but with far less frequency and typically in response to prosecution evidence. Id.

[26] See, e.g., Paul C. Giannelli, The Abuse of Scientific Evidence in Criminal Cases: The Need for Independent Crime Laboratories, 4 Va. J. Soc. Pol’y & L. 439, 441 (1997).

[27] See NAS Report, supra note 2, at 23–24.

[28] See Crist & Requarth, supra note 89; Radley Balko, A Brief History of Forensics, Wash. Post (Apr. 21, 2015), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-watch/wp/2015/04/21/a-brief-history-of-forensics/; Jennifer L. Mnookin et al., The Need for a Research Culture in the Forensic Sciences, 58 UCLA L. Rev. 725, 766 (2011).

[29] Michael J. Saks & David L. Faigman, Failed Forensics: How Forensic Science Lost Its Way and How It Might Yet Find It, 4 Ann. Rev. L. & Soc. Sci. 149, 153 (2008); Mnookin et al., supra note 116, at 766. See also Paul C. Giannelli, Forensic Science: Why No Research?, 38 Fordham Urb. L.J. 503, 508-09 (2010).

[30] Saks, supra note 111, at 1092. See also Crist & Requarth, supra note 89.

[31] See Saks and Faigman, supra note 117 at 157–58.

[32] See Race and Ethnicity, Prison Policy Initiative, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/research/race_and_ethnicity/ (consolidating data on, inter alia, overrepresentation of people of color in the criminal legal system).

[33] Criminal Justice Facts, Sentencing Project, https://www.sentencingproject.org/criminal-justice-facts (last visited Mar. 4, 2021); Levin, supra note 88, at 260–61.

[34] See % Exonerations by Contributing Factors, Nat’l Registry Of Exonerations, http://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/ExonerationsContribFactorsByCrime.aspx (last visited Mar. 4, 2021).

[35] The National Registry of Exonerations lists 665 wrongful convictions as involving faulty forensic evidence as a contributing factor. Id. Of those, it lists 301 as Black and 54 as “Hispanic.” Search Results, Nat’l Registry of Exonerations, http://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/detaillist.aspx?View={FAF6EDDB-5A68-4F8F-8A52-2C61F5BF9EA7}&FilterField1=F%5Fx002f%5FMFE&FilterValue1=8%5FF%2FMFE (last visited Mar. 4, 2021).

With George Floyd, a Raging Debate Over Bias in the Science of Death With George Floyd, a Raging Debate Over Bias in the Science of Death

By Shaila Dewan, The New York Times, (April 14, 2021 Updated April 16, 2021)

With George Floyd, a Raging Debate Over Bias in the Science of Death

Critics say the profession of forensic pathology has been slow to acknowledge how big a role bias may play in decisions such as whether to classify a death in police custody as a homicide.

The memorial to George Floyd outside Cup Foods. The question of how Mr. Floyd died is central to the case against Derek Chauvin.Credit...Joshua Rashaad McFadden for The New York Times

By Shaila Dewan

Published April 14, 2021 Updated April 16, 2021

MINNEAPOLIS — From the beginning, the death of George Floyd disrupted the field of forensic pathology in much of the way it challenged policing.

Days after Mr. Floyd’s death on May 25, prosecutors said it was caused not just by the police officer kneeling on his neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds, but also by his underlying health conditions and drug use.

Critics protested that the finding reflected racial bias — and served as a prime example of how forensic pathology has failed to do enough to counter its own subjectivity in decisions such as whether to classify a death in police custody as a homicide.

The public criticism helped expose long-simmering tensions within the small but influential world of medical examiners, drawing in some of the experts who consulted on the case or may be called to testify for the defense.

Some of them have vigorously objected to a study, published just before the trial began, that measured bias among forensic pathologists, taking the unusual step of asking that it be retracted.

The timing of the paper was “particularly alarming in the era of Black Lives Matter, critical race theory, riots and so forth,” wrote Dr. Brian L. Peterson, the Milwaukee County medical examiner, in one of several emails to a private forensic pathology email list obtained by The New York Times. “What is woke today is fodder tomorrow.”

Medical examiners say that of course they, like everyone else, have biases — but that they already have ample systems in place, including courtroom scrutiny of their decisions, to curb them. In fact, Dr. Peterson wrote, the notion that cause-of-death determinations are objective and science-based is “basically nonsense.”

“Is there anyone in our profession that has not, at one point or another, quipped about ‘spinning the wheel of death’ and picking one?”

After the Journal of Forensic Sciences published the study, which showed that medically irrelevant information like the victim’s race can sway the decisions of forensic pathologists, Dr. Peterson, along with Dr. David Fowler and Dr. William Oliver, signed a letter asking that it be retracted, calling it “fatally flawed.”

The Journal of Forensic Sciences, which published the paper, declined to retract it.

Dr. Brian L. Peterson has said that the idea that cause-of-death decisions are objective and science-based is “basically nonsense.” He is set be called as a witness by the defense for Mr. Chauvin.Credit...Sara Stathas

Dr. Fowler, who testified on Wednesday for Mr. Chauvin’s defense, is the former chief medical examiner of Maryland, and Dr. Oliver, who was also listed as a potential defense witness, is a professor at the Brody School of Medicine in North Carolina.

Dr. Fowler testified that there were so many factors contributing to Mr. Floyd’s death, including heart disease and high blood pressure, that he would have classified the manner of death as “undetermined” rather than as “homicide.”

Dr. Fowler is named in a civil rights lawsuit filed by the family of Anton Black, an unarmed Black teenager who died in Baltimore in 2018 after officers held him down in the prone position for about six minutes. The family has compared his death to the death of Mr. Floyd. Dr. Fowler’s office classified it as an accident.

Complaints of bias have long hung over the Floyd case. Four days after Mr. Floyd’s death, the county prosecutors listed what they said were preliminary autopsy findings in a criminal complaint that many said undermined their own case against the officers involved.

An opinion piece written by 12 doctors and published in Scientific American called the complaint “a weaponization of medical language” that “reinforced white supremacy at the torment of Black Americans.”

“They took standard components of a preliminary autopsy report to cast doubt, to sow uncertainty; to gaslight America into thinking we didn’t see what we know we saw,” they wrote.

The state attorney general, Keith Ellison, soon took over the case.

By then the Floyd family had hired two forensic pathologists, a white man and a Black woman, to conduct their own autopsies. Both of them, Dr. Michael Baden and Dr. Allecia Wilson, said that asphyxia, or deprivation of oxygen, was the cause of death and placed the blame squarely on the police officers involved.

Second autopsies have long been a common practice, in part because medical examiners have longstanding relationships with prosecutors and the police, raising concerns about their objectivity in deaths involving officers.

But in Mr. Floyd’s case the main professional organization for forensic pathologists, the National Association of Medical Examiners, took the unusual step of issuing a statement that many perceived as critical of the practice.

The association’s primary goal seemed to be to defend Dr. Andrew Baker, the Hennepin County medical examiner and a past president of the association, who performed the Floyd autopsy.

Dr. Andrew Baker, the Hennepin County medical examiner who performed George Floyd’s official autopsy, testified in court on Friday.Credit...Still image, via Court TV

After his report, which classified the death as a homicide and listed heart disease, fentanyl and methamphetamine as contributing factors to Mr. Floyd’s death, was released last June, an emergency fence and concrete barricades were erected around his office.

The statement from the association took issue with news reports that described the private autopsies by Drs. Baden and Wilson as “independent,” implying that Dr. Baker’s was compromised.

“The independent autopsy is the one done by the medical examiner who, unlike private pathologists, do not have an incentive to come up with a certain view,” it said.

But private autopsies are a routine stream of income for many forensic pathologists, and the association began to receive complaints, including one from one of the country’s most renowned forensic pathologists, Cyril Wecht. Another came from Dr. Wilson, one of the pathologists hired by the Floyd family.

“Our fight should not be between each other but working together to understand why Black men are dying so quickly when taken into police custody,” Dr. Wilson wrote, saying the Floyd family’s consulting with her was akin to a patient’s getting a second opinion. She noted that the practice had never before earned a rebuke from the association.

“I am particularly offended as I have watched Dr. Baden make controversial opinions my entire career, but when another, a Black woman, has a controversial opinion, it is handled quite differently,” she wrote.

The medical examiners association retracted the statement.

An image taken from a video of Dr. Allecia Wilson delivering her autopsy findings in Mr. Floyd’s death. Dr. Wilson and Dr. Michael Baden, both forensic pathologists, were hired by the Floyd family to conduct their own autopsies.

Its leaders also invited Dr. Joye Carter to help develop a protocol for second autopsies. Dr. Carter says she is the first Black woman to be board certified in forensic pathology in the United States and the first Black person appointed to be a chief medical examiner, a position she held in Washington, D.C., and Houston. She consulted on the Floyd case for the prosecution.

Dr. Carter had discontinued her membership in the national association five years before. “I never felt welcome. I never felt included,” she said. “You know, there’s a difference between feeling welcomed and feeling tolerated.”

She agreed to come back and was hopeful that things had changed, especially after she was asked to chair a new diversity committee.

Because of that, she said, she did not anticipate any controversy when she signed on to the study on bias among forensic pathologists, led by Itiel Dror, a cognitive neuroscientist who specializes in expert error and bias. The authors examined 10 years of children’s death certificates in Nevada and found that the deaths of Black children were a little more likely to be classified as homicides, rather than accidents, compared with deaths of white children.

They also sent a death scenario to forensic pathologists, and found that those who responded were more likely to rule it a homicide when the child in the scenario was Black and cared for by the mother’s boyfriend than when the child was white and cared for by a grandmother.

The authors said the study was merely a starting point for research and suggested that forensic pathologists further explore how and when contextual information should be used, and be transparent when using it.

Four of the study’s authors were forensic pathologists, including Dr. Carter.

In February, Dr. Peterson, the potential defense witness in Mr. Floyd’s case, filed an ethics complaint against all four, accusing them of “conduct averse to the best interests and purposes” of the profession.

“By basically accusing every member of ‘unconscious’ racism, a charge impossible to either prove or refute, members will henceforth need to confront this bogus issue whenever testifying in court,” he wrote in the complaint, a copy of which was obtained by The Times.

Dr. Peterson did not respond to a message left with his office, where a spokeswoman said he was on vacation. Ethics complaints are supposed to be confidential, and the accused doctors declined to discuss it or did not respond to a request for comment.

The vitriolic response to the study surprised Dr. Carter.

“I was kind of blown away by what appears to be very irate reaction,” she said. “And I’m not sure if everyone has truly read the article for what it is. It’s an article that suggests, let’s be aware of this, let’s be proactive in this. I don’t think anybody, any physician of color, would say, ‘Gee, this is earthshaking news.’”

Cognitive bias in forensic pathology decisions

Itiel Dror PhD, Judy Melinek MD, Jonathan L. Arden MD, Jeff Kukucka PhD, Sarah Hawkins JD, Joye Carter MD, PhD, Daniel S. Atherton MD, Journal of Forensic Sciences (20 February 2021))

This is the study referenced in the article you just read ("With George Floyd, A Raging Debate in the Science of Death").

Reading the actual study is useful beacause (a) it gives us practice reading a scientific study (which is unfamiliar teritory for many of us; (b) it's an example of a well structured study (in contrast to the many poorly structured studies we'll read about this semester); and (c) it provides a concrete example of of the role racial bias can play in subjective forensic decisions.

Opinion: I was wrongfully arrested because of facial recognition. Why are police allowed to use it? Opinion: I was wrongfully arrested because of facial recognition. Why are police allowed to use it?

By Robert Williams, The New York Times (June 24, 2020)

By Robert Williams

June 24, 2020

Robert Williams is a resident of Farmington Hills, Mich., and client of the American Civil Liberties Union.

I never thought I’d have to explain to my daughters why Daddy got arrested. How does one explain to two little girls that a computer got it wrong, but the police listened to it anyway?

While I was leaving work in January, my wife called and said a police officer had called and said I needed to turn myself in. I told her it was probably a prank. But as I pulled up to my house, a Detroit squad car was waiting in front. When I pulled into the driveway, the squad car swooped in from behind to block my SUV — as if I would make a run for it. One officer jumped out and asked if I was Robert Williams. I said I was. He told me I was under arrest. When I asked for a reason, he showed me a piece of paper with my name on it. The words “arrest warrant” and “felony larceny” were all I could make out.

By then, my wife, Melissa, was outside with our youngest in her arms, and my older daughter was peeking around my wife trying to see what was happening. I told my older daughter to go back inside, that the cops were making a mistake and that Daddy would be back in a minute.

But I wasn’t back in a minute. I was handcuffed and taken to the Detroit Detention Center.

As any other person would be, I was angry that this was happening to me. As any other black man would be, I had to consider what could happen if I asked too many questions or displayed my anger openly — even though I knew I had done nothing wrong.

When we arrived at the detention center, I was patted down probably seven times, asked to remove the strings from my shoes and hoodie and fingerprinted. They also took my mugshot. No one would tell me what crime they thought I’d committed. A full 18 hours went by. I spent the night on the floor of a filthy, overcrowded cell next to an overflowing trash can.

The next morning, two officers asked if I’d ever been to a Shinola watch store in Detroit. I said once, many years ago. They showed me a blurry surveillance camera photo of a black man and asked if it was me. I chuckled a bit. “No, that is not me.” He showed me another photo and said, “So I guess this isn’t you either?” I picked up the piece of paper, put it next to my face and said, “I hope you guys don’t think that all black men look alike.”

The cops looked at each other. I heard one say that “the computer must have gotten it wrong.” I asked if I was free to go now, and they said no. I was released from detention later that evening, after nearly 30 hours in holding.

I eventually got more information from an attorney referred to me by the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan. Someone had stolen watches, and the store owner provided surveillance footage to the Detroit Police Department. They sent that footage to the Michigan State Police, who then ran it through their facial-recognition system. That system incorrectly spit out a photograph of me pulled from an old driver’s license picture.

Federal studies have shown that facial-recognition systems misidentify Asian and black people up to 100 times more often than white people. Why is law enforcement even allowed to use such technology when it obviously doesn’t work? I get angry when I hear companies, politicians and police talk about how this technology isn’t dangerous or flawed. What’s worse is that, before this happened to me, I actually believed them. I thought, what’s so terrible if they’re not invading our privacy and all they’re doing is using this technology to narrow in on a group of suspects?

I wouldn’t be surprised if others like me became suspects but didn’t know that a flawed technology made them guilty in the eyes of the law. I wouldn’t have known that facial recognition was used to arrest me had it not been for the cops who let it slip while interrogating me.

The ACLU is lodging a complaint against the police department on my behalf, but that likely won’t change much. My daughters can’t unsee me being handcuffed and put into a police car. But they can see me use this experience to bring some good into the world. That means helping make sure my daughters don’t grow up in a world where their driver’s license or Facebook photos could be used to target, track or harm them.

Even if this technology does become accurate (at the expense of people like me), I don’t want my daughters’ faces to be part of some government database. I don’t want cops showing up at their door because they were recorded at a protest the government didn’t like. I don’t want this technology automating and worsening the racist policies we’re protesting. I don’t want them to have a police record for something they didn’t do — like I now do.

I keep thinking about how lucky I was to have spent only one night in jail — as traumatizing as it was. Many black people won’t be so lucky. My family and I don’t want to live with that fear. I don’t want anyone to live with that fear.

Editor’s note: In response to request for comment from The Post, Nicole Kirkwood of the Detroit Police Department submitted this response: “The Detroit Police Department (DPD) does not make arrests based solely on Facial Recognition. Facial Recognition software is an investigative tool that is used to generate leads only. ... In reference to this case, an investigation was conducted. The investigator reviewed video, interviewed witnesses, conducted a photo line-up, and submitted a warrant package containing facts and circumstances, to the Wayne County Prosecutors Office (WCPO) for review and approval. The WCPO in return recommended charges that was endorsed by the magistrate/judge for Retail Fraud – First Degree." She also noted: “[T]his case predates our current policy, which only allows the use of the Facial Recognition software after a violent crime has been committed.”

Fingerprints and Race

This video is part of a series of lectures on the history of fingerprinting, focusing on the social, political, scientific and technological developments that have made fingerprinting such an important part of forensic science today.

As the project's website explains:

"Ever since the time of its invention in the 19th century, modern fingerprint identification was envisioned as a tool for controlling colonial subjects and immigrant populations. Whether in colonial India, Argentina, or the U.S. West Coast – a site of strong anti-Chinese racism – fingerprint identification seemed to hold the promise of giving the state stronger control over particular groups that were viewed in some way as “untrustworthy,” a racist idea that equated group affiliation with criminality and propensity to lie about one’s identity.

Another way that the history of fingerprinting has overlapped with ideas about race, identity, and difference has been in scientific research. Starting in the late 19th century, those with an academic interest in fingerprints have tried to investigate whether certain kinds of fingerprint patterns could be associated with particular “races” (they cannot). Those who carried out this research soon came to realize what a futile endeavor it was. Nonetheless, the search for evidence of “racial” identity and difference in fingerprints would continue in another form: studies of the frequency with which different fingerprint characteristics appear in different racially-defined groups.

. . . .

In the early 20th century, . . . an assumption that many people held – [was] that science could authoritatively explain the differences between “races.”This assumption motivated decades of research in dermatoglyphics, the scientific study of fingerprints and other ridged skin. "

Writing Reflection #2 Writing Reflection #2

Please go to our Moodle Page and under "Class 2" you will find the prompt and submission folder for Writing Reflection #2.

1.2.1 OPTIONAL Class 2 1.2.1 OPTIONAL Class 2

OPTIONAL: A Tale of Two Dauberts: Discriminatory Effects of Scientific Reliability Screening

Jurs, Andrew W. and DeVito, Scott, 79 Ohio State Law Journal 1107 (2018)

This article may be of interest to those looking at the impact of Daubert in the civil system.

From the article:

"[W]e confirmed that Daubert does have a disparate impact on communities of color, leading to their disproportionate exclusion from federal court. We found that when the federal system adopted the stricter standard of Daubert in 1993, there was a disproportionate and negative impact on filings from African-American plaintiffs along with a corresponding rise in filings from white plaintiffs.

Our research shows that, in response to Daubert, black plaintiffs were less likely to file in federal court, and once they were pushed out of the civil justice system, they remained out. In essence, the Daubert admissibility standard impacts filings exactly like a method of tort reform, but only for claimants of

color."

OPTIONAL: Colonial Beginnings of Fingerprints

This is another video in the series on the history of fingerprinting. Watch if you are interested in learning how and why British colonial India provided the setting for the early development of modern fingerprint identification practices.

OPTIONAL Fingerprints: the Convoluted Patterns of Racism | Digital History

OPTIONAL: Forensic scientists are generally whiter, less diverse than US population they serve, study says

Tami Abdollah, USA TODAY (Sept. 8, 2022)

A yearlong study examining ethnic and racial diversity in forensic science has found that the varying disciplines, which frequently work closely with law enforcement, are also generally whiter than the U.S. population it serves.

The report, published Thursday in Forensic Science International: Synergy, is one of only a few that have looked at the relative representation of people of color in forensic science-related fields today. After an early energetic debate among the future authors, they quickly discovered one reason why so little had been done on the subject: There is next to no good data.

Even forensic-related professional organizations like the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS) or the National Association of Medical Examiners that could easily survey its membership and disclose demographics, don't report statistics on its racial and ethnic makeup, the report notes.

The study states it was forced to focus on larger datasets for fields such as psychology or pathology, which include forensics; or census data that's not always about forensics-related jobs and therefore muddied; or data from an outside career and job search platform that couldn't be independently verified. The study notes it also was unable to account for an entire group of individuals who didn't self-identify as one race.

The findings highlighted large disparities between the general U.S. population and those working in these social science- or science-related fields. By and large, those who identified as Asian were overrepresented across most forensic science-related jobs, except as specialized psychologists. But individuals identifying as Black, Hispanic and Indigenous were largely underrepresented across the board.

Andrea Roth, a Berkeley Law professor whose research focuses on the use of forensic science in criminal trials and reviewed the study at USA TODAY's request, said its efforts to roughly identify the numbers of African American forensic odontologists by looking at African American dentists, for example, likely means that the actual diversity numbers are even worse. That's because dentistry was an already established professional path in the 20th century for African Americans — and they might be less interested in assisting law enforcement investigations given understandable historic distrust.

The study notes that forensic science has historically framed itself as being "objective," but that is largely a myth, which has in and of itself discouraged people of color from participating. Roth explains that this is because science in general has been used to entrench ideas of race.

Roth notes that some "biometric" techniques had their beginnings in racism or eugenics to try to identify "criminal" or "abnormal" biological attributes. The man sometimes called the father of fingerprinting, Sir Francis Galton, is known for being an unapologetic racist, among other examples, Roth added.

"That doesn't mean that modern forensic techniques are racist," Roth said. "But there is a history there that might explain some cultural trends in terms of how the discipline developed and its interaction with culture and society."

While limited in nature, the report still aims to get at the broader consequences of an overall lack of diversity.

Close relationship forensic scientists have with law enforcement

Unless there is greater diversity in the field, much of the technology being developed maybe without thinking about the impacts on people of color, said An-Di Yim, a forensic anthropologist and assistant professor at Truman State University in Missouri and lead author of the paper.

Yim noted that DNA technology that builds out what a face might look like may not account for the natural gradient in skin colors and the fact that race is often a complex, socially constructed and self-identifying attribute – not just linked to skin color, as it is in the U.S.

The study also notes the close relationship forensic scientists have with law enforcement and the disproportionate number of people of color in forensic DNA databases, "which mirrors the disproportionate number of BIPOC individuals in the criminal justice system" and may further add to distrust of the system.

"Especially because forensic science is so police adjacent, whatever lack of diversity is contributing to what's happening in law enforcement," said Yim, referencing reports on systemic racism, "I'd say there's a huge parallel."

A 2011 study found that less than 15% of the AAFS membership self-identified as being a member of a minority group, based on gender, race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. A more recent study this year found the AAFS anthropology section to be at least 87% white, but only a third of it took surveys and many of those who did were students.

Fewer people of color in the world of forensics means they are likely to play less of a role in helping craft key privacy provisions around the future of familial DNA searches, an effort that is ongoing amid that professional community and state legislatures, Roth said. It's an area of science that has had a disproportionately high impact on communities of color given the greater numbers of Black and brown individuals already in law enforcement DNA databases.

The study also found that of the 104 U.S. schools the Education Department classifies as "historically Black colleges and universities," only 13, or 12.5% offer forensic science-related programming – and less than half offer a bachelor's or certificate in forensic science. Of the 46 U.S. programs accredited by the Forensic Science Education Programs Accreditation Commission, the study noted only two are at an HBCU.

'You don’t want to have blind spots'

The study did find that students in the 2020 class of college graduates who identified as Hispanic were "well-represented" in forensic science and technology, as well as forensic psychology.

Mark Barash, an assistant professor and forensic science program coordinator at San Jose State University, said that while diversity conceptually is very important, it's always best to simply ensure workers are qualified regardless of their background. Barash believes the ideal way to address underrepresentation is by helping educate the new generation of students from these communities and help them gain the same chances those from overrepresented populations might have.

The authors advocated for more active reporting around diversity and inclusion from forensic science organizations to better study the issue in the future. They also noted the need for more effective strategies for recruitment, retention, and promotion, as well as mentorship — at least once there is more data and it is better understood.

Max Houck, a forensic anthropologist and the editor-in-chief of the forensic science journal that published the study, told USA TODAY that he believes such diversity is crucial to forensic science-related professions because 98% of the workforce is made up of civil servants, and it makes sense for them to represent the populations they are serving.

"You're looking for a group of people that may not agree but can come to agreements," Houck said. "You don't want to be surrounded by people who are exactly like you, or you tend to solve problems the same way. From an organizational perspective, it’s not good."

He added: "You don’t want to have blind spots and you certainly would if you had an all-white all-male forensic lab."

Tami Abdollah is a USA TODAY national correspondent covering inequities in the criminal justice system. Send tips via direct message @latams or email tami(at)usatoday.com

OPTIONAL: Op-Ed: Black people are wrongly convicted more than any other group. We can prevent this OPTIONAL: Op-Ed: Black people are wrongly convicted more than any other group. We can prevent this

BY CHRISTINA SWARNS, Los Angeles Times (OCT. 7, 2022)

Available at this link.

One of my clients, Duane Buck, was convicted of murder in 1997 and sentenced to death, in part because an expert testified that he was more likely to commit criminal acts of violence in the future because he is Black. That racist testimony led the Supreme Court to overturn Buck’s death sentence in 2017.

The belief that race is a proxy for criminality pervades the U.S. legal system. Indeed, a new report from the National Registry of Exonerations — researched by social scientists, lawyers and journalists and examining the 3,248 exonerations that have occurred in the U.S. since 1989 — demonstrates that race is a powerful driver of wrongful convictions. Among the report’s findings:

- Black people are seven times more likely than white people to be falsely convicted of serious crimes.

- Even accounting for crime rates, Black people convicted of murder are almost 80% more likely to be innocent than other people convicted of murder.

- The exonerations of innocent Black people convicted of murder were almost 50% more likely to include misconduct by police officers than the exonerations of white people convicted of murder.

- Innocent Black people were almost eight times more likely than innocent white people to be falsely convicted of rape.

- Innocent Black people were 19 times more likely to be convicted of drug crimes than innocent white people, even though there was no meaningful disparity in the rate at which Black and white people sell or possess drugs.

On their own, these numbers cannot fully illustrate the harm caused by this kind of bias and inequity. Consider the case of Calvin Johnson, who has served as a board member at the Innocence Project. Johnson was tried for two sexual assaults in two different Georgia counties in the 1980s. In Clayton County, Johnson and his attorney were sometimes the only Black people in the courtroom. An all-white jury rejected the alibi testimony offered by four Black witnesses and deliberated just 45 minutes before returning with a guilty verdict. Johnson was sentenced to life in prison.

Seven months later, he went on trial for the second assault in Fulton County. Even though the Clayton County conviction made the prosecution’s case against him much stronger, he was acquitted by a jury composed of five white people and seven Black people. More than a decade after Johnson’s conviction, the Innocence Project secured DNA testing of the rape kit in the Clayton County case and conclusively established his innocence. His wrongful conviction was overturned.

The outcomes of the cases of Duane Buck and Calvin Johnson are only two examples of the persistence of racial bias in the criminal legal system. Finding long-term solutions for ensuring the fair and equitable administration of justice in the American legal system will be a complex, multigenerational undertaking. But real opportunities to begin the process of reform already exist.

For starters, anyone who works with or within the legal system should make a commitment to ensuring that their work is consistently guided by scholarship, laws and policies that mitigate racial bias in criminal legal system decision-making. For example, Illinois — a state where 90% of known false confession cases involved Black and brown people — became the first state in the country, in 2021, to prohibit police officers from using deception when interrogating people younger than 18.

We must continue to ensure the reliability of DNA testing. The report found that routinized DNA testing had all but eliminated wrongful sexual assault convictions based on cross-racial misidentifications in cases with biological evidence. This is transformative, given the extensive history of innocent Black men wrongfully convicted of such crimes. But as new technology allows the analysis of ever smaller and more complex samples of DNA, that technology must also be subject to robust scrutiny.

Every prosecutor’s office should have an independent, appropriately staffed conviction integrity unit — a team tasked with reviewing convictions presenting credible claims of innocence that works collaboratively with defense counsel on reinvestigations. As of June there were 101 such units in the U.S. The National Registry’s report found that they were responsible for 1 out of 3 exonerations from 2015 to 2022.

Crime labs can play a significant role in preventing and ameliorating racial disproportionality in wrongful drug convictions. Because the Houston crime lab conducts post-conviction testing of drugs, it uncovered 157 cases where no controlled substance was involved. Expanding this practice to additional jurisdictions, conducting such testing at the beginning of the process, and requiring crime lab testing before permitting a guilty plea in drug cases should significantly diminish wrongful convictions and reduce racial inequities.

There should be more data collection, transparency, evaluation and regulation of technologies such as facial recognition software that currently penalize communities of color. In addition, affected communities should be included in the decision-making process.

The National Registry report makes clear that for Black people, the legal process looks different, the outcomes are more severe and getting a remedy for system atrocities can take a very long time. There are no easy answers, but progress will need to start with making a commitment to recognizing the racial disparities that continue to distort the administration of justice.

Christina Swarns is the executive director of the Innocence Project.

OPTIONAL: Garbage In, Gospel Out: How data-driven policing technologies entrench historic racism and tech-wash bias in the criminal legal system

NACDL’S TASK FORCE ON PREDICTIVE POLICING (2021)

1.3 Class 3: Admissibility under the Frye standard 1.3 Class 3: Admissibility under the Frye standard

Frye v. United States Frye v. United States

This case (a) set the prior standard for admission of expert testimony in the federal courts until it was replaced by the Daubert standard and (b) sets the current standard for admission in some states, including New York and New Jersey.

FRYE v. UNITED STATES.

(Court of Appeals of District of Columbia.

Submitted November 7, 1923.

Decided December 3, 1923.)

No. 3968.

J. Criminal law <&wkey;472 — Expert testimony, explaining systolic blood pressure deception test, inadmissible.

The systolic blood pressure deception test, based on the theory that truth is spontaneous and comes without conscious effort, while the utterance of a falsehood requires a conscious effort, which is reflected in the blood pressure, held not to have such a scientific recognition among psychological and physiological authorities as would justify the courts in admitting expert testimony on defendant’s behalf, deduced from experiments thus far made.

2. Criminal iaw <&wkey;472 — Principle must be generally accepted, to render export testimony admissible.

While the courts will go a long way in admitting expert testimony, deduced from a well-recognized scientific principle or discovery, the thing from which the deduction is made must be sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it • belongs.

Appeal from the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia.

James Alphonzo,Frye was convicted of murder, and he appeals.

Affirmed.

Richard V. Mattingly and Foster Wood, both of Washington, D. C., for appellant.

Peyton Gordon and J. H. Bilbrey, both of Washington, D. C., for the United States.

Before SMYTH, Chief Justice, VAN QR5DED, Associate Justice, and MARTIN, Presiding Judge of the United States Court of Customs Appeals.

Appellant, defendant below, was convicted of the crime of murder in the second degree, and from the judgment prosecutes this appeal.

A single assignment of error is presented for our consideration. In the course of the trial counsel for defendant offered an expert witness to testify to the result of a deception test made upon defendant. The test is described as the systolic blood pressm-e deception test. It is asserted that blood pressure is influenced by change in the emotions of the witness, and that the systolic blood pressure rises are brought about by nervous impulses sent to the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. Scientific experiments, it is claimed, have demonstrated that fear, rage, and pain always produce a rise of systolic blood pressure, and that conscious deception or falsehood, concealment of facts, or guilt of crime, accompanied by fear of detection when the person is under examination, raises the systolic blood pressure in a curve, which corresponds exactly to the struggle going on in the subject’s mind, between fear and attempted control of that fear, as the exam*1014ination touches the vital points in respect of which he is attempting to deceive the examiner.

In other words, the theory seems to be that truth is spontaneous, and comes without conscious effort, while the utterance of a falsehood re-citares a conscious effort, which is reflected in the blood pressure. The rise thus produced is easily detected and distinguished from the rise produced by mere fear of the examination itself. In the former instance, the pressure rises higher than in the latter, and is more pronounced as the examination proceeds, while in the latter case, if the subject is telling the truth, the pressure registers highest at the beginning of the examination, and gradually diminishes as the examination proceeds.

Prior to the trial defendant was subjected to this deception test, and counsel offered the scientist who conducted the test as an expert to testify to the results obtained. The offer was objected to by counsel for the government, and the court sustained the objection. Counsel for defendant then offered to have the proffered witness conduct a test in the presence of the jury. This also was denied.

Counsel for defendant, in their able presentation of the novel question involved, correctly state in their brief that no cases directly in point have been found. The broad ground, however, upon which they plant their case, is succinctly stated in their brief as follows:

“The rule is that the opinions of experts or skilled witnesses are admissible in evidence in those cases in which the matter of inquiry is such that inexperienced persons are unlikely to prove capable of forming a correct judgment upon it, for the reason that the subject-matter so far partakes of a science, art, or trade as to require a previous habit or experience or study in it, in order to acquire a knowledge of it. When the question involved does not lie within the range of common experience or common knowledge, but requires special experience or special knowledge, then the opinions of witnesses skilled in that particular science, art, or trade to which the question relates are admissible in evidence.”

[1,2] Numerous cases are cited in support of this rule. Just when a scientific principle or discovery crosses the line between the experimental and demonstrable stages is difficult to define. Somewhere in this twilight zone the evidential force of the principle must be recognized, and while courts will go a long way in admitting expert testimony deduced from a well-recognized scientific principle or discovery, the thing from which the deduction is made must be sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs.

We think the systolic blood pressure deception test has not yet gained such standing and scientific recognition among physiological and psychological authorities as would justify the courts in admitting expert testimony deduced from the discovery, development, and experiments thus far made.

The judgment is affirmed.

Motion to Exclude Fingerprint Evidence Under Frye Motion to Exclude Fingerprint Evidence Under Frye

This is a defense motion to exclude fingerprint evidence in a criminal case under Frye (which was referred to as the Frye/Dyas test in D.C.). The actual document is sitting under the "Class 3" folder on Moodle - please go to Moodle to read the document. This motion:

(a) illustrates the application of the Frye test;

(b) considers the question of who counts as the relevant scientific community;

(c) describes the fingerprint identification process;

(d) describes the critique of that process; and

(e) illustrates the relationship of Rule 403 to Frye.

Government's Reply to the Motion to Exclude Fingerprint Evidence under Frye Government's Reply to the Motion to Exclude Fingerprint Evidence under Frye

This is the government's response to the motion to exclude fingerprint evidence that you just read. This excerpt illustrates the different view the government takes on the Frye test, the definition of the relevant scientific community, and the meaning of the 2009 NRC Report.

Please read:

- Pages 1-5

- Pages 13-40

- Pages 46 & 47

- Page 49 (starting with point "3") to page 51

- The last line of page 57 to page 58

- And skim the index at the end

The excerpt is a pdf posted on our Mooodle site under "Class 3."

Innocence Project Amicus Brief in New York v. Williams Innocence Project Amicus Brief in New York v. Williams

This amicus brief makes four recommendations to the New York Court of Appeals that are essentially four critiques of the way the Frye standard is handled in the New York. (This excerpt includes the first three – we’ll read the fourth recommendation later.)

(You don’t need to know much about the underlying case to understand the amicus argument, but the legal question was “whether the trial court should have held a Frye hearing with respect to the admissibility of low copy number (LCN) DNA evidence and the results of a statistical analysis conducted using the proprietary forensic statistical tool (FST) developed and controlled by the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner (OCME).”

|

APL-2018-00151 |

|

|

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Respondents, —against — CADMAN WILLIAMS, Defendant-Appellant,

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Respondents, —against — ELIJAH FOSTER-BEY, Defendant-Appellant. |

|

|

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE THE INNOCENCE PROJECT |

|

|

M. Chris Fabricant

|

Konrad Cailteux |

|

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae The Innocence Project |

|

|

Date Completed: [●] |

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT......................................................................... 3

1. TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

In re Accutane Litig.,

234 N.J. 340 (2018)..................................................................................... 29

Ex parte Chaney,

563 S.W.3d 239 (Tex. Crim. App. 2018)........................................................ 8

Chesson v. Montgomery Mutual Ins. Co.,

75 A.3d 932 (Md. 2013)............................................................................... 16

Coble v. State,

330 S.W.3d 253 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010)...................................................... 16

State ex rel. Collins v. Superior Court,

644 P.2d 1266 (Ariz. 1982).......................................................................... 22

Commonwealth v. Foley,